COPYRIGHT 2026 SCRIPTURE CENTRAL FOUNDATION: A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REGISTERED 501(C)(3). EIN: 39-2827600

Historical Context and Background of D&C 89

Brief Synopsis by Steven C. Harper

Most everyone drank in the 1820s and 1830s, Joseph Smith included.1 Distillers in his upstate New York neighborhood made corn whiskey and sent 65,277 gallons of it and 69 tons of beer to market on the Erie Canal the year after Joseph’s first vision of God and Christ.2 Newspapers in the towns near Joseph’s home advertised cheap alcohol, printed recipes for making beer, and sold the ingredients. One scholar aptly described Joseph’s America as “the alcoholic republic.”3

Joseph’s father confessed in a patriarchal blessing to his son Hyrum in 1834 that he had been “out of the way through wine” sometimes in the past, but “Joseph Sr.’s drinking was not excessive for that time and place.”4 Nearly all males drank and so did many women and children. Members of all social classes drank. They drank morning, mid-day, and evening, at funerals and parties, militia musters, and church socials.

“The thing has arrived to such a height,” one widely quoted temperance advocate noted, “that we are actually threatened with becoming a nation of drunkards.”5 America’s desire for alcohol and the rise of temperance generated diverse opinions that led Joseph Smith to ask questions. Between 1831 and 1836, the cry for abstinence gained momentum. In 1833, in the middle of this controversy, the Lord revealed where the Saints should stand relative to alcohol consumption.

Americans consumed enormous amounts of meat. Authorities often condoned this practice in winter but worried that too much consumption could result in overstimulation. All authorities agreed that use of all stimulants, in which they included herbs, meats, coffee, and tea, could lead to overstimulation and, therefore, disease. The most radical authorities, especially Sylvester Graham, thought that foods much more tasty than a Graham cracker (named for Sylvester) were very dangerous. He urged complete abstinence from coffee, tea, meat, spices, and condiments. Granting that coffee and tea were stimulants, other authorities thought Graham’s position too extreme and believed that healthy people could consume these drinks in moderation without causing disease.

By 1800 the influential doctor Benjamin Rush had persuaded many authorities that all disease could be traced to overstimulation, and therefore all illness could be treated by so-called “heroic” methods of releasing the patient’s excess energy. Joseph Smith’s brother Alvin died in 1823 after a doctor’s dose of mercurous chloride blocked rather than purged his digestive system. Joseph Smith and most Latter-day Saints had little confidence in the fledgling medical profession and its heroic practices. In the days of primitive diagnostic techniques before diseases were well understood, an 1831 revelation to Joseph Smith taught Saints that “whosoever among you are sick, and have not faith to be healed, but believe, shall be nourished with all tenderness, with herbs and mild food, and that not by the hand of an enemy” (D&C 42:43). This counsel matched most closely the relatively innocuous naturopathic practices of Samuel Thomson, and many Latter-day Saints followed his advice until advances in medical science increased their confidence in professionals late in the nineteenth century.6

The world into which the Lord revealed the Word of Wisdom was quite different from our own. Advances in medical science have provided much more certainty about the dangers of consuming many of the substances that were thought by many in Joseph Smith’s world to have medicinal value. Moreover, his contemporaries were in the process of reconsidering their certainty about the value of alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, meats, fruits, and some herbs. There was no prevailing view to which everyone subscribed, even inside the Church. There were more questions than answers.

Outspoken temperance crusaders added tobacco to their list of noxious substances in the 1830s, and it became as warmly debated as alcohol. Was tobacco a powerful medicine capable of curing all kinds of afflictions or a noxious weed that was loathsome to the lungs? Was it a filthy habit or a socially acceptable pastime? Uncertainty about these questions may have been the immediate catalyst for Joseph Smith’s reception of the Word of Wisdom.

Nearly two dozen men gathered for school in a second-story room of Newel and Ann Whitney’s Kirtland, Ohio, store on February 27, 1833. “The first thing they did,” according to Brigham Young,

was to light their pipes, and, while smoking, talk about the great things of the kingdom, and spit all over the room, and as soon as the pipe was out of their mouths a large chew of tobacco would then be taken. Often when the Prophet entered the room to give the school instructions he would find himself in a cloud of tobacco smoke. This, and the complaints of his wife at having to clean so filthy a floor, made the Prophet think upon the matter and he inquired of the Lord.7

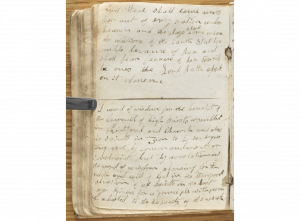

With one of the elders for his scribe and perhaps one or two others present, Joseph Smith, in a nearby room, received the revelation known as the Word of Wisdom. Besides answering the immediate question of whether the brethren should smoke or chew tobacco, or “the filthy weed and their disgusting slobbering and spitting,” as one colorful account put it, the revelation clarified several other issues that were being debated by Joseph’s contemporaries.8

One of the most unusual aspects of the Word of Wisdom is that although it came in answer to pressing questions in 1833, its primary purpose is to forewarn future saints of conspiracies to undermine their agency. Notice the doctrinal basis of the revelation. It assumes, as an earlier revelation to Joseph Smith said, that “the spirit and the body are the soul of man” (D&C 88:15). Whereas some Christians think of the body as evil and look forward to leaving it behind at death, Latter-day Saints regard the body as godly and look forward to a literal, glorious resurrection. They believe God and Christ are perfectly embodied and that through the process of birth, earth life, death, and resurrection, men and women are being created in their image. To preserve the soul and its agency to act for itself, the Lord forbade drinking strong drinks and also wine, unless it was for the sacrament.9

The revelation instructs people how to act relative to distilled (“strong”) and fermented drinks, domesticated and wild animals, tobacco, hot drinks, grains, herbs, fruits, and vegetables. These are all things God has made and given mankind to use. The revelation tells us how to use them in ways that please God. “All these to be used with prudence and thanksgiving,” for example, speaking of herbs and fruits (D&C 89:11), or “they are to be used sparingly,” speaking of meat and poultry (v. 12). A seldom-noted aspect of stewardship in the Word of Wisdom is the repeated command to use what God has provided “with thanksgiving” (vv. 11–12). The repeated emphasis is on righteous use, not abuse. God created this earth and its life-sustaining abundance to be used by wise stewards who thankfully acknowledge him, not abused by the ungrateful or gluttonous.

The Word of Wisdom is more than a simple health code. It is a covenant. Elder Boyd K. Packer testified that “while the Word of Wisdom requires strict obedience, in return it promises health, great treasures of knowledge, and that redemption bought for us by the Lamb of God, who was slain that we might be redeemed.”10

Some critics of the Word of Wisdom assert that because it addressed the circumstances of Joseph Smith’s world, it must not be real revelation. That is silly, since it assumes that a revelation that answers timely questions is somehow suspect. What good is an irrelevant revelation? Another simplistic assumption is that the Word of Wisdom mimicked the prevailing idea of Joseph’s time. There was no prevailing idea, no single opinion. Then as now, there were many competing ideas, debate rather than consensus.

The Word of Wisdom sorts out and clarifies the strengths and weaknesses among the variety of opinions. Forbidding the ingestion of nearly all alcoholic beverages, as well as coffee, tea, and tobacco, the revelation ran counter to the mainstream culture. It was consistent, however, with an emerging medical opinion regarding meats, herbs, fruits, and vegetables. The revelation did not give Joseph Smith, his followers, or family members what they wanted to hear. Many of the men in the church used tobacco. Emma Smith took coffee and tea. Joseph liked whiskey.11 They all consumed more meat than was needful.12 The revelation was not what they wanted to hear. It was the wisdom they needed to hear.

1. Saints Herald, June 1, 1881, 163, 167.

2. Western Farmer, January 30, 1822.

3. W.J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

4. Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 42.

5. Quoted in Rorabaugh, Alcoholic Republic, 216.

6. Cecil O. Samuelson Jr., “Medical Practices,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols. (New York: MacMillan, 1992), 2:875.

7. Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F.D. Richards, 1855–86), 12:158, February 8, 1868.

8. Lyndon W. Cook, ed., David Whitmer Interviews (Orem, Utah: Grandin, 1991), 204.

9. “Revelation, 27 February 1833 [D&C 89],” p. [113], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2020.

10. Boyd K. Packer, “The Word of Wisdom: The Principle and the Promises,” Ensign, May 1996, 18.

11. Joseph Smith address to the Mormons at Nauvoo on Last Sunday of April 1841, Reverend Julius A. Reed Collection, box 2, folder 15, Iowa State Historical Society, Iowa City, Iowa.

12. L E Bush, “The Word of Wisdom in Early Nineteenth-Century Perspective,” Dialogue, 1981 (14:3), 53, 63.

Additional Context by Casey Paul Griffiths

From Doctrine and Covenants Minute

In the upper floor of the Newel K. Whitney store in Kirtland, Ohio, the first School of the Prophets was held in a small room. In this school local priesthood holders gathered to receive instruction in the principles of the gospel. While no contemporaneous sources describing the circumstances under which JS dictated this 27 February 1833 revelation have been located, later accounts indicate that it was recorded in connection with the activities of the School of the Prophets. According to Brigham Young, heavy tobacco use—in the form of both smoking and chewing—among members of the school, combined with Emma Smith’s and others’ complaints about cleaning tobacco juice from the floor, led JS “to inquire of the Lord with regard to use of tobacco” and “to the conduct of the elders with this particular practice.” He later said, “I think I am well acquainted with the circumstances which led to the giving of the Word of Wisdom as any man in the Church, although I was not present at the time to witness them.”1

In a discourse given in 1868 Brigham described the meetings of the School of the Prophets, saying, “When they assembled together in this room after breakfast, the first thing they did was to light their pipes, and while smoking, talk about the great things of the kingdom and spit all over the room, and as soon as the pipe was out of their mouths a large chew of tobacco would then be taken.” The distraction of the smoke “and the complaints of his [Joseph’s] wife,” Brigham added, “made the Prophet think upon the matter, and he inquired of the Lord relating to the conduct of the Elders in using tobacco.”2 It was in these circumstances that one of the most unique and distinguishing traits of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came into existence: the health code known as the Word of Wisdom.

See “Historical Introduction,” Revelation, 27 February 1833 [D&C 89]

1. The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, ed. Richard Van Wagoner, 2009, 2:2532.

2. Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, 2:2532.