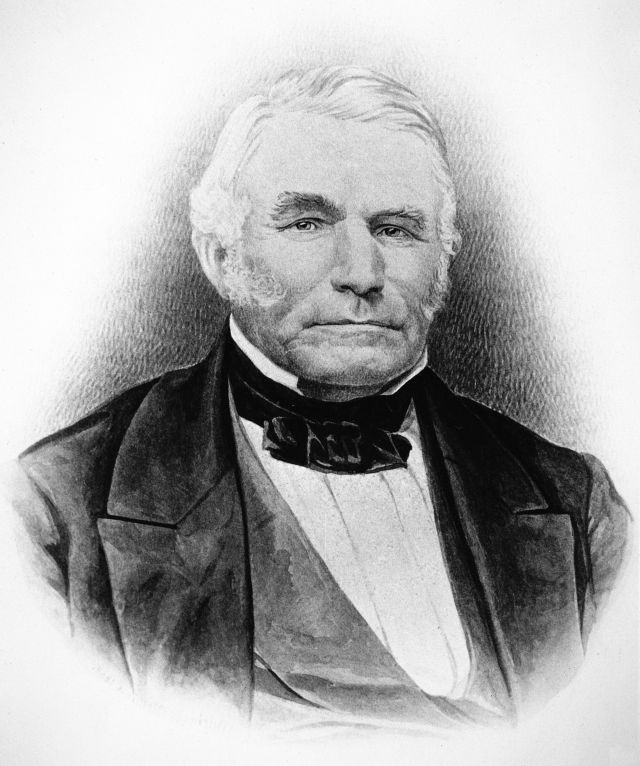

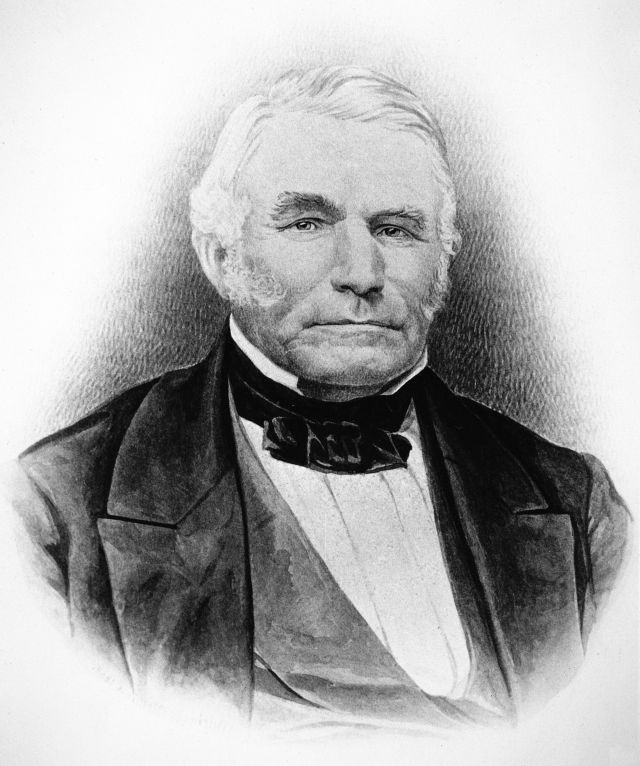

Lilburn W. Boggs

(1792-1861)

By Susan Easton Black

After the War of 1812, Boggs became a bookkeeper in the Insurance Bank of Kentucky. By 1816 he had moved on to Missouri to seek his fortune. In St. Louis, he was employed as a head cashier in the newly created Bank of Missouri. In August 1817 he married Julia Anne Bent, the daughter of a prominent jurist and political figure in Missouri. Within a year, Boggs and his wife had moved to Franklin, a major outfitting post for the Rocky Mountain fur trade. There he was successful in shipping merchandise to the frontier settlements of St. Charles and Fort Osage.

By 1826 Boggs and his family had resettled in the western frontier outpost of Independence. It was there that he took an interest in politics. He ran unopposed for the state senate. Having enjoyed his political experience in Jefferson City, in 1828 he ran for a second term. It was while in his second term in office that he made the acquaintance of Peter Whitmer Jr., a missionary sent to the borders of the Lamanites. Peter sewed a suit for him.

In 1832 Boggs was put forward by the Democratic Party as their candidate for lieutenant governor to serve with gubernatorial candidate Daniel Dunklin. Both candidates were elected by a large majority. As to his new responsibilities, Boggs was only required to be in Jefferson City when the legislature was in session. Most of his time was spent in Independence. While holding the office of lieutenant governor, on July 20, 1833, he was seen sitting on his horse, watching mobs destroy the W. W. Phelps printing shop. He also witnessed the tarring and feathering of Bishop Edward Partridge, Charles Allen, and others on the public square in Independence. Boggs was never punished for his role in the religious persecution of the Saints.

In January 1835 at a Democratic Party convention, Boggs was given the nod to run for governor. Parley P. Pratt wrote, “The majority of the State so far countenanced these outrages that they actually elected Lilburn W. Boggs … [to] the executive chair, instead of suspending him by the neck, between the heavens and the earth, as his crimes justly merited.”1 Boggs took over as governor of Missouri on September 30, 1836, when Governor Daniel Dunklin resigned.

Boggs served as Missouri’s sixth governor from 1836 to 1840. His administration was fraught with difficulties. The financial Panic of 1837 blocked his ability to fulfill campaign promises to expend state funds to improve railways and waterways. He pressed for state funds to build a new capitol building in Jefferson City. When funds were proffered, questions were raised about distribution. Boggs escaped formal censure on this issue but not on orders directed against the Latter-day Saints. He regarded “his duty as chief executive of the state and commander-in-chief of the militia to enforce the laws and suppress insurrections” committed by the Latter-day Saints.2 On October 27, 1838, he issued an extermination order giving legal license to exterminate the “Mormons” or drive them from the state.3

Latter-day Saints held Governor Boggs responsible for the atrocities they experienced in Missouri. The Prophet Joseph Smith said of Boggs, “All earth and hell cannot deny that a baser knave, a greater traitor, and a more wholesale butcher, or murderer of mankind ever went untried, unpunished, and unhung.”4 Brigham Young said, “If those laws [guaranteed by the Constitution] had been executed they would have hung Governor Boggs … with many others, between the heavens and the earth, or shot them as traitors to the Government.”5

Boggs weathered the criticism. When his term as governor ended on August 3, 1840, he returned to Independence and announced plans to run for the US Senate in 1842. His plans were nearly put to rest on May 6, 1842. While sitting in his study at home in Independence, an estimated seventeen small balls were discharged through the study window into the chair on which he sat. Not all of the slugs entered his body. Four slugs entered his neck and head, two penetrating his skull.

On circumstantial evidence, Sheriff J. H. Reynolds of Independence issued a reward of $3,000 for the capture of Orrin Porter Rockwell for the attempted assassination of Boggs. In the meanwhile, a type of conspiracy theory was created with rumors placing Joseph Smith as the alleged mastermind who ordered Rockwell to assassinate former governor Boggs. Boggs believed the rumors and signed his name to an affidavit, or complaint, against Rockwell for the attempted murder. Public outrage and strong anti-Mormon sentiments in northern Missouri demanded his capture. For nine months, Rockwell was confined in the Independence jail. He was never convicted of the crime.

Boggs recovered from the assassination attempt and lived for another nineteen years. He went on to serve in the US Senate, representing the state of Missouri. After completing his senate term, he and his family packed up their belongings and moved to northern California. In California, Boggs served as the alcalde (mayor) of the Northern District. By 1849 his interests had turned from politics to the gold rush. It does not appear that he was successful in the gold rush, for Parley P. Pratt wrote, “Lilburn W. Boggs is dragging out a remnant of existence in California, with the mark of Cain upon his brow, and the fear of Cain within his heart, lest he that findeth him shall slay him. He is a living stink, and will go down to posterity with the credit of a wholesale murderer.”6

Boggs would not have agreed with Pratt’s assessment, for he had a comfortable life, residing on his prosperous farm in Napa, California. He died on March 19, 1861, at age sixty-seven.

1. Parley P. Pratt Jr., ed., Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 85.

2. Buel Leopard and Floyd C. Shoemaker, Messages and Proclamations of the Governors of Missouri, 1:387, as cited in Joseph F. Gordon, The Public Career of Lilburn W. Boggs (1949), 98.

3. Documents, Containing the Correspondence, Orders, etc., Relation to the Disturbance with the Mormons Published by order of the General Assembly (Fayette, 1841). 20, as cited in Gordon, Public Career of Lilburn W. Boggs, 98.

4. Smith, History of the Church, 1:435.

5. Journal History of the Church, October 25, 1857.

6. Pratt, Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, 181

Additional Resources

- Biography of Lilburn W. Boggs (josephsmithpapers.org)