Revelations and Translations |

Episode 8

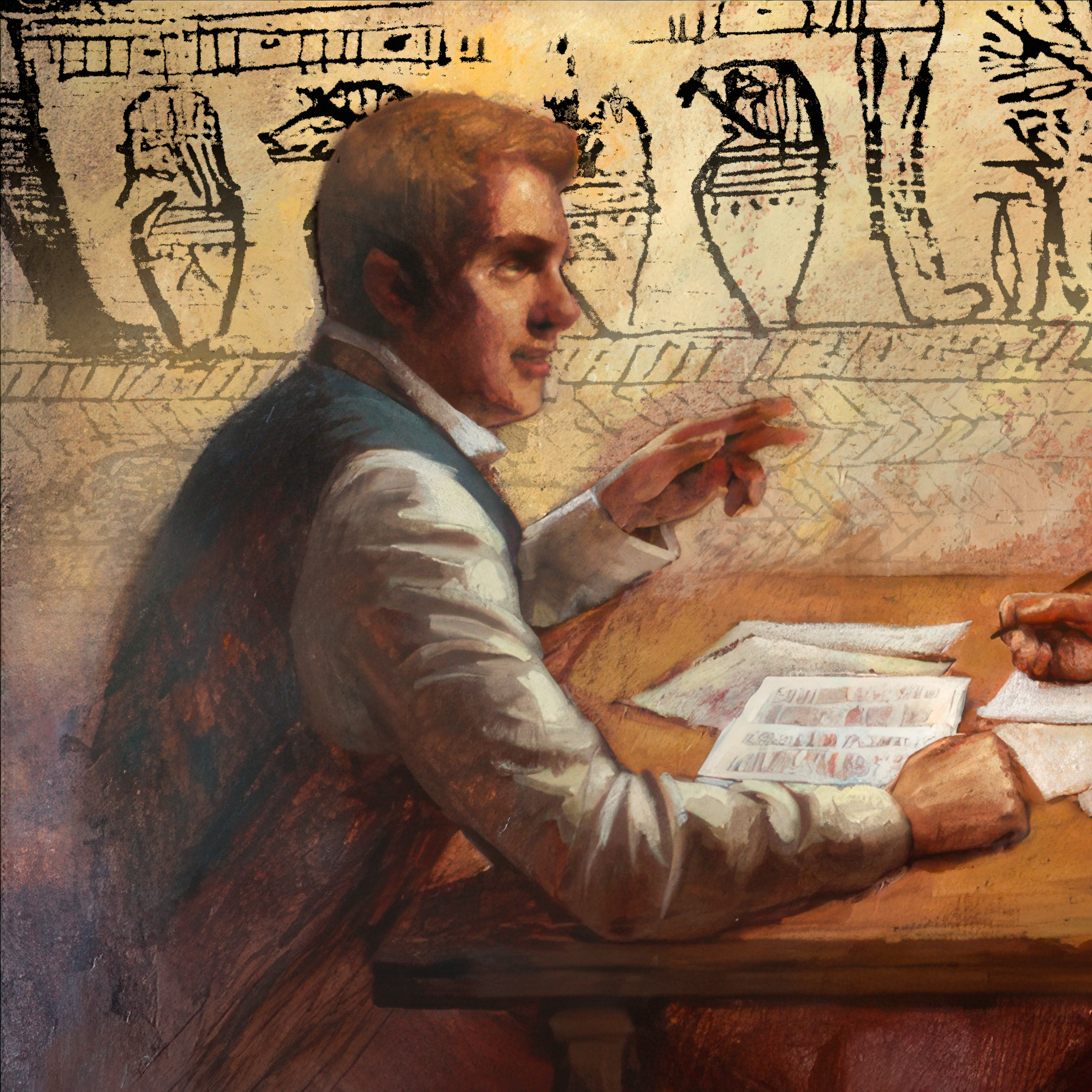

The Abraham Facsimile Conundrum: Is it All or Nothing?

56 min

In Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles found in our Pearl of Great Price, he ties all three of them to Abraham, yet when some modern Egyptologists look at those same facsimiles today, they say they have nothing to do with Abraham. One is simply an embalming scene, they say, one a disc representing the eye of Horus, and one a judgment scene from an Egyptian Book of the Dead. So, is this an either-or, sudden-death scenario? Must we, in the name of honesty and rationality, pick a side here? Must we either throw out modern Egyptologists by choosing to stand with the Prophet Joseph on the one hand, or throw out Joseph by choosing to align with modern Egyptologists on the other? Or is there a reconciliatory third path in which both interpretations can be true at the same time? In this episode of Church History Matters, we tackle this important question by looking at some of the best scholarship on this issue, and on our way, we’ll also briefly look at something called the Kirtland Egyptian Papers and discuss a minor controversy associated with those.

Revelations and Translations |

- Show Notes

- Transcript

Key Takeaways

- The Church possesses documents today known as the Kirtland Egyptian papers—labeled the Abraham Manuscripts and the Egyptian Language Manuscripts. These papers have been the subject of a mild controversy because they contain hieroglyphs copied from the Egyptian papyrus accompanied by English interpretations of those hieroglyphs that are clearly incorrect. This confirms only that neither Joseph Smith nor his associates were capable of translating Egyptian in a scholarly way (despite their obvious efforts at trying). These papers were never published, and Church leaders never claimed they were accurate, received by revelation, or official in any way. Nevertheless, critics have tried to use these papers to discredit Joseph Smith’s ability to translate by revelation, which is, in fact, a non sequitur.

- The largest controversy surrounding the Book of Abraham is connected to the three facsimiles published in our Pearl of Great Price. According to some Egyptologists, the translations contained on the facsimiles published with the Book of Abraham are interpreted incorrectly. They bear close resemblance to facsimiles found in the Egyptian Book of Breathings and Book of the Dead and Egyptian artifacts called hypocephali, none of which explicitly have anything to do with Abraham.

- However, some of the best scholarship on this issue tells us that a traditional Egyptian understanding of the facsimiles is not the only—or best—way to understand them. At the time period and place scholars estimate the mummies and papyri originated, people of several cultures were coexisting, including Egyptians, Greeks, and Jews. Evidence suggests that there was a significant cross-cultural exchange between Jews, Greeks, and Egyptians in Egypt, influencing their religious practices and art.

- In fact, after Joseph Smith’s death two papyri were discovered dating from roughly the same time as Joseph Smith’s papyri were discovered which associate Abraham with a lion couch scene (akin to Facsimile 1) and the Wedjat Eye of Horus (akin to Facsimile 2), which is solidly confirms the idea that such facsimiles were being used to tell stories about Abraham in ancient Egypt. Additionally, The Testament of Abraham, discovered after Joseph Smith’s time, links Abraham to the Egyptian Book of the Dead (related to Facsimile 3), giving further evidence that such facsimiles were used to depict Abraham-related narratives in ancient Egypt.

- There have been many scholarly breakthroughs which bolster the case for the plausibility of the ancient origins of the Book of Abraham. But although much evidence now supports the authenticity of its narrative, it is important to remember that the veracity of the Book of Abraham cannot be determined by scholarly debate; it lies in the eternal truths it teaches and the spirit it conveys. We are taught in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, specifically in the Doctrine and Covenants, to “seek learning by study and also by faith.” The Book of Abraham and the information surrounding it should be no exception.

Related Resources

Muhlestein, Kerry. “Interpreting the Abraham Facsimiles.” Meridian Magazine, Sept. 1, 2014.

“Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham,” Gospel Topics essay, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“New Video Explores the Historical Credibility of the Book of Abraham,” Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Abraham and Idrimi.” Book of Abraham Insight #1, Pearl of Great Price Central

“Jews in Ancient Egypt.” Book of Abraham Insight #11, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Abrahamic Legends and Lore.” Book of Abraham Insight #12, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The Ancient Egyptian View of Abraham.” Book of Abraham Insight #13, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The Ancient Owners of the Joseph Smith Papyri.” Book of Abraham Insight #14, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Abrahamic Astronomy.” Book of Abraham Insight #15, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Shinehah, The Sun.” Book of Abraham Insight #16, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Ancient Near Eastern Creation Myths.” Book of Abraham Insight #20, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“By His Own Hand Upon Papyrus.” Book of Abraham Insight #23, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Approaching the Facsimiles.” Book of Abraham Insight #27, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Facsimile 1 as a Sacrifice Scene.” Book of Abraham Insight #28, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The Idolatrous Priest (Facsimile 1, Figure 3).” Book of Abraham Insight #29, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The Purpose and Function of the Egyptian Hypocephalus.” Book of Abraham Insight #30, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The Four Sons of Horus (Facsimile 2, Figure 6).” Book of Abraham Insight #32, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Facsimile 3: Judgment Scene vs. Presentation Scene.” Book of Abraham Insight #34, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“Abraham and Osiris (Facsimile 3, Figure 1).” Book of Abraham Insight #35, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“What Egyptian Papyri Did Joseph Smith Possess?” Book of Abraham Insight #37, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The ‘Kirtland Egyptian Papers’ and the Book of Abraham.” Book of Abraham Insight #38, Pearl of Great Price Central.

“The Relationship Between the Book of Abraham and the Joseph Smith Papyri.” Book of Abraham Insight #40, Pearl of Great Price Central.

Gee, John, “Research and Perspectives: Abraham in Ancient Egyptian Texts.” Ensign, 22. (July 1992): 60-62

Scott Woodward: Hi, this is Scott from Church History Matters. As we near the completion of this series, we want to hear your questions about the Book of Abraham. In two weeks we will be pleased to have as our special guest Dr. Kerry Muhlestein to help us respond to your questions. He is an Egyptologist and an author and scholar on all things related to the Book of Abraham, and Casey and I have drawn heavily from Dr. Muhlestein’s excellent research for each of our Book of Abraham episodes in this series. So please submit your thoughtful questions anytime before October 18, 2023 to podcasts@scripturecentral.org. Let us know your name, where you’re from, and try to keep each question as concise as possible when you email them in. That helps out a lot. Okay, now on to the episode. In Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles found in our Pearl of Great Price, he ties all three of them to Abraham, yet when some modern Egyptologists look at those same facsimiles today, they say they have nothing to do with Abraham. One is simply an embalming scene, they say, one a disc representing the eye of Horus, and one a judgment scene from an Egyptian Book of the Dead. So, is this an either-or, sudden-death scenario? Must we, in the name of honesty and rationality, pick a side here? Must we either throw out modern Egyptologists by choosing to stand with the Prophet Joseph on the one hand, or throw out Joseph by choosing to align with modern Egyptologists on the other? Or is there a reconciliatory third path in which both interpretations can be true at the same time? In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we tackle this important question by looking at some of the best scholarship on this issue, and on our way, we’ll also briefly look at something called the Kirtland Egyptian Papers and discuss a minor controversy associated with those. I’m Scott Woodward, and my co-host is Casey Griffiths, and today we dive into our eighth episode in this series dealing with Joseph Smith’s non-Book-of-Mormon translations and revelations. Hello, Casey.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Hello, Scott. Welcome back.

Scott Woodward: Yeah. Excited to dive back into some Book of Abraham. I think we left it on a pretty major cliffhanger last time.

Casey Paul Griffiths: We did. I hope nobody died of a heart attack. This is so exciting.

Scott Woodward: So let’s back up. Do you mind just reviewing for a second, Casey? Like, how did we even get the Book of Abraham?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: What’s up with the two scrolls, the four mummies, the eleven fragments, and then the kind of translation options and theories about how it was translated?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: How fast can you do it? This is the challenge. Let’s see.

Casey Paul Griffiths: I’m a college professor, so I don’t know if I can do anything quickly. It all started 2,200 years ago. No, I guess we started with Napoleon.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Napoleon invades Egypt.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Napoleon and his people plunder, rob, and steal all these sacred antiquities from Egypt, and it creates an Egyptological craze that we’re still dealing with today.

Scott Woodward: Egyptomania.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Egyptomania. I went to Egypt last year, and I get it. Egypt is amazing. And I was only there for three days, but the stuff I saw just blew my mind. Just so cool. And there’s so much to see there, and it’s such a fascinating culture, and to add more, it’s even linked to the Bible. You go to the Egyptian museum, and they have the earliest reference in writing to the children of Israel in this big stela that’s on display in the Grand Egyptian Museum.

Scott Woodward: Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths: So everybody in the 19th century is fascinated by Egyptology and Egyptian antiquities. And this guy named Antonio Lebolo, who is one of the more famous archaeologists, grave robber, whatever you want to call the guy, who secures this cache and collection. Lebolo dies in 1830, his collection makes its way to the United States, where a man named Michael Chandler—and we don’t know what Michael Chandler’s relationship was to Antonio Lebolo—starts traveling around displaying a set of papyri, a collection of mummies.

Scott Woodward: Like, eleven mummies, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Eleven mummies and some papyrus scrolls, yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah. And Michael Chandler really isn’t one of those “It belongs in a museum” kind of dealers, because he’s selling the stuff as he goes. He’s selling the mummies when he comes to Cleveland, Ohio. Joseph Smith is nearby in Kirtland. They meet together. Joseph Smith examines some of the papyri, which contemporary people describe as a large scroll, a small scroll, and other Egyptian materials, which we think are these papyri fragments we’ve been talking about, along with four mummies. Joseph Smith identifies the papyri as containing the writings of Abraham and Joseph in the court of Pharaoh. Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat Joseph.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Church purchases them. Joseph Smith starts to translate them. The translation isn’t really published until Nauvoo, but it forms today what is the Book of Abraham. And the translation published in Nauvoo also includes these three facsimiles that are still, to this day, included in every edition of the Pearl of Great Price, Facsimile 1, 2, and 3, which is what our focus is on today. After Joseph Smith’s death, the Egyptian materials, including the mummies and the papyri, go to his mother. When she dies in 1856, Emma Smith and Lewis Bidemon sell them to Abel Combs. He sells part of the collection to a museum in St. Louis, then it’s taken to Chicago, and in 1871 there’s a big fire that destroys at least two of the mummies, and we think the scrolls associated with this. However, in 1946 the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art acquires several papyri fragments, one of which appears to have Facsimile 1 on it. They, in turn, contact a professor at the University of Utah. He contacts the church. The church obtains the papyri fragments and publishes them in the church magazine and allows both Latter-day Saint and non-Latter-day Saint Egyptologists to examine the papyri.

Scott Woodward: That’s, like, 1967, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: 1967 is when this all happens.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: The papyri do not contain the writings of Abraham. In fact, we would say they aren’t even linked to Abraham if it wasn’t for Facsimile 1 being on one of the papyri fragments.

Scott Woodward: Is that a point of controversy at all, or…?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. A lot of people were like, this is proof Joseph Smith isn’t a prophet.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But last time we presented three theories of translation. Number 1: If you believe the fragments that we have are the source of the Book of Abraham, then yeah, Joseph Smith’s not a prophet. They’re an Egyptian text, primarily one called the Book of Breathings, that was a funerary text.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: However, theory number 2 is that we’re missing the source of the Book of Abraham. And this lines up well with contemporary witnesses who saw the Egyptian materials, and what they described was really different from what we have. Most of them described two rolls—we already mentioned this, but—a long roll and a smaller roll, then fragments. It’s pretty consistent from the witness statements that the fragments had been glued to this piece of paper that they were found on and put in a glass frame by 1837 to try and preserve them.

Scott Woodward: That’s early.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah. It seems like that’s what we have.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: So theory number 2 is we just don’t have the source of the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward: Because those scrolls were destroyed in the Chicago Fire of 1871?

Casey Paul Griffiths: They were either destroyed, or they’re lost. Maybe somebody will find them in their attic someday, but it seems like they went to that museum that was eventually burned down, the Wood Museum in Chicago.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Theory number 3 is the catalyst theory. That is that none of the papyri were the source of the Book of Abraham, that the papyri were a catalyst that opened Joseph Smith to receiving revelations that then constitute the Book of Abraham. This is consistent with almost every form of translation Joseph Smith describes, and he’s fairly transparent about it, too, to just basically say, I don’t know Reformed Egyptian. I don’t know Hebrew. I don’t know Greek. I don’t know Egyptian. I did this by the gift and inspiration of God. And Latter-day Saints are very comfortable with this. That’s the Book of Mormon. That’s the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible.

Scott Woodward: If he’s a true prophet, he can do that kind of stuff.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Prophets can do stuff by revelation like that.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, he can do that kind of stuff. So all those things seem to account for the text of the Book of Abraham, but the cliffhanger we left everybody on was the facsimiles in the Book of Abraham, which a lot of antagonists towards the church will say, Joseph Smith just got them wrong. He just got them wrong.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And so that’s what we’re going to focus on today.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But before we do that, we want to take a quick side tangent. And I know everybody wants to talk about the facsimiles, and we’re teasing here, but we need to at least mention another little facet of the Book of Abraham, and that is what are called the Kirtland Egyptian Papers.

Scott Woodward: Ooh. Now, what are the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, Casey?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Okay. So when we’ve been talking about this, we’ve been talking about the mummies and the papyri. Those stay with Lucy Mack Smith, go to Emma Smith, and most of them go to the museum, eventually.

Scott Woodward: For those eleven fragments that end up in the Met.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Those eleven fragments that end up in the Met.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: The Kirtland Egyptian papers don’t go with them. They come west with the church. And they are papers that the church has always had in its collection. They were published by the Joseph Smith Papers project. In fact, I have here with me a lovely facsimile edition that was published in 2018. Full disclosure, most of the stuff that the Joseph Smith Papers project publishes in print is available on their website for free.

Scott Woodward: Whoa, whoa, so I don’t have to buy those super expensive books?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, yeah. I’m looking at this book, and I used my research funds to purchase it, and it’s $90. So if you have $90—

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: —by all means, go and drop that.

Scott Woodward: Go for it.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah. If you’re a completist like me, and you’ve got to have the whole Joseph Smith Papers set in print, go for that. But if you’re a poor student, or just more thrifty than I am, all this stuff is typically available on the Joseph Smith Papers site within a year after it’s been published. So, I mean, you’re two clicks away. Just go and look at this right now. The Kirtland Egyptian papers were taken west when the church went west. They consist primarily of two collections: number 1, what’s known as the Abraham Manuscripts, which contain the extant English text of the Book of Abraham. These manuscripts date between mid-1835, when Joseph Smith starts translating—he gets the Egyptian materials in the summer of 1835—and early 1842. That’s the accounting for the second period of translation takes place in Nauvoo.

Scott Woodward: And do we have all the Book of Abraham accounted for in those manuscripts?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yes.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And we also can do a pretty good job identifying the scribes that Joseph worked with. So W. W. Phelps, who we’ve mentioned, was one of the earliest people to see the Egyptian materials, was really excited about them, thought it would help the case of the Book of Mormon. Warren Parrish, who eventually apostatizes from the church, but he’s one of our main sources that he says Joseph told him the Book of Abraham came by direct inspiration. We’ve got Frederick G. Williams, who’s a member of the First Presidency, who is excommunicated but comes back and dies in the church, and Willard Richards, who—Willard Richards is close secretary, close friend of Joseph Smith. He’s in Carthage Jail when Joseph is killed.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: The second collection is called the Egyptian Language Manuscripts, and these are kind of a hodgepodge of documents that transcribe portions of the characters from the Egyptian papyri and appear to systematize an understanding of the Egyptian language. These are in the handwritings of W. W. Phelps, Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and Warren Parrish. So the Egyptian language manuscripts are, they took a character off the papyri, and then they would sometimes write off to the side, oh, this is what this means, and they’re wrong. There’s no polite way to put it. They’re just wrong.

Scott Woodward: So they’re trying to decipher the hieroglyph, one hieroglyph at a time, and they create this—they call it an alphabet, right? The grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: By the way, so they’re trying to create this alphabet about the same time that something called the Rosetta Stone is being worked on by experts, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: Can you line those timetables up at all for us?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, and maybe we need to—I thought I wouldn’t have to do this in my classes, but I need to, because I was talking about the Book of Abraham and I actually said, “This was before the Rosetta Stone.” And all my classes started giggling, and I was like, “Why are you laughing?”

Scott Woodward: Why is that funny?

Casey Paul Griffiths: And they go, “Well, you mean that Joseph Smith didn’t have a computer program that teaches him different languages?” I was like, “No—guys, there’s an actual Rosetta Stone that the program is named after.” But basically, nobody can translate Egyptian until the Rosetta Stone is discovered. The Rosetta Stone is a stela. It’s an inscription on rock that’s discovered in 1799 that has inscriptions on it in Egyptian hieroglyphics, in Greek, and the third language is Demotic, I think?

Scott Woodward: Demotic. Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Demotic. Okay. And since Greek is a known language, now they’re able to compare, because all these inscriptions say the same thing, and they’re able to use it as a key to start to break open the Egyptian.

Scott Woodward: The code of the hieroglyphics.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, this isn’t like today, where findings are published on the internet and everybody knows about them. It takes decades for the scholarship to circulate. And at this point the scholarship really hasn’t made it to America. So it seems like the Kirtland Egyptian papers are showing that Joseph Smith and his contemporaries were trying to find a secular means of translating the Book of Abraham. They’re taking the characters out. They’re writing an interpretation off to the side. They’re trying to figure out what it is. And like I said, these are just there. They’re in the Joseph Smith papers.

Scott Woodward: And they’re not getting it right at all, right? Like—

Casey Paul Griffiths: They’re not right.

Scott Woodward: —they’re little hieroglyphs with their description next to it. Like, the description has nothing to do with what the hieroglyphs actually mean as modern Egyptologists currently understand it, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: I mean, I think the main takeaway from the Kirtland Egyptian papers is that Joseph Smith didn’t know Egyptian, though he doesn’t claim to ever.

Scott Woodward: But he was so fascinated with it, right? He wanted—he loved ancient languages, and he wanted to try to figure it out.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: But Joseph as a scholar of Egyptology, not so hot. As a revelator, fantastic.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah. So here’s just four points about the Kirtland Egyptian papers. We took these from Pearl of Great Price Central. Go and check out the article there. Number 1: We have these papers, but the extent of Joseph Smith’s involvement in their creation is unknown. There is some of his handwriting on one manuscript and his signature on another, but there’s not enough evidence to clearly demonstrate that Joseph Smith is the real driver behind this. Most of the manuscripts are in W. W. Phelps’s handwriting. He’s a close associate of Joseph Smith, but we don’t know to what degree Joseph Smith is working on this. Second, it’s unclear when in 1835 Joseph Smith began creating the Book of Abraham manuscripts or what the relationship is between the Egyptian language manuscripts and the Book of Abraham. So we know he starts on the Book of Abraham in 1835. We don’t really know what the timeline is and how these things fit into it, okay?

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Third, while considerable overlap of themes exists between the Book of Abraham and the Egyptian language documents, most of the Book of Abraham is not textually dependent on any of the extant Egyptian language documents. The inverse is also true. Most of the content of the Egyptian language documents is independent of the Book of Abraham. So the themes overlap a little bit, but what they’re writing in the Egyptian language documents and what is in the Book of Abraham don’t have a strong connection to each other. Okay?

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And finally, the Egyptian language documents were never presented as an authoritative revelation by Joseph Smith or any other person. This is from the introduction to the JSP volume on the Kirtland Egyptian Papers.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: What emerges most clearly from a closer look at the Kirtland Egyptian Papers is the fact that there is nothing official or final about them. They are fluid, exploratory, confidential, and hence free of any possibility of intention of fraud or deception. So when you look at these papers, it seems like they’re messing around with Egyptian and they’re trying to figure it out, but they don’t publish them. They don’t put them out there, they don’t say that they’re the real deal. They’re just exploring the characters that are in some of the papyri and trying to figure out on their own what it is.

Scott Woodward: So it’s kind of them just kind of noodling around with the hieroglyphics and trying to figure stuff out.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: As a pet side project, but not anything official or claiming to be revelation.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah. One of the mistakes we sometimes make is Joseph Smith said that his translation projects came by the gift and power of God. And sometimes in doing that, we tend to belittle the value of academic scholarship. Joseph Smith did not do that. Joseph Smith felt that academic scholarship was really valid. He tried to learn Hebrew. He’s learning Greek and German.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: When Martin Harris asks if he can take some of the characters from the Book of Mormon plates to a scholar and have them look at them, Joseph Smith is all for it. He copies the characters onto a piece of paper. Martin Harris goes to at least three different people.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: The most famous one is Charles Anthon. Allows secular scholars to look at this. Like, I think if there was a way to translate the Book of Mormon or these papyri through secular means, they would have been all for it. They’re open to that avenue.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But ultimately in these situations, there isn’t. I mean, Charles Anthon says that he thought the characters Martin Harris showed him were authentic, but nobody knows Egyptian at that time, including Charles Anthon.

Scott Woodward: Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And so he wouldn’t have been able to translate them if they had brought them to him.

Scott Woodward: Yeah. Joseph Smith is not averse to scholarship. He’s not averse to scholars. He didn’t see scholars as the enemy to revealed religion. He felt like study and faith went together in perfect harmony.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: I think that’s consistent in all of his projects, in the School of the Prophets. . . In fact, my theory is that it was because of the Book of Mormon translation that he got so interested in ancient languages. Like, his original experience as a translator, a 23-year-old young man, I think that had a major lasting imprint on him, and so he wanted to learn ancient languages, actually.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: I think that plays out the rest of his life.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, I think that’s a fair assessment. So these Kirtland Egyptian papers, we just wanted to acknowledge that they’re there, but it’s kind of like the theory number one: Everybody says these are wrong. They’re wrong. The main thing that they prove is that Joseph Smith didn’t know Egyptian.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And that’s okay. Joseph Smith didn’t claim that he knew Egyptian.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But they also show that they’re putting in some “by study and also by faith.” They’re trying to figure this out on their own. But they’re not the source of the Book of Abraham, and they don’t demonstrate that Joseph Smith knew how to do an academic translation of Egyptian, which is okay. That’s never what he or the church or anybody has claimed about the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward: Gotcha. Okay, so the major controversy surrounding the Kirtland Egyptian papers is that the conclusions they came to in terms of the meaning of the hieroglyphs are just flat wrong. And so that’s it. Now, whatever assumptions you want to bring to that, that’s where things can get complicated, but the facts of the matter are that they got it wrong. Their efforts to translate hieroglyphics in an academic way proved erroneous, basically.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, if that’s what this is. I mean, we’re making some assumptions here.

Scott Woodward: Right. So, yeah, so the assumptions you bring to that are where that can get complicated, and that can get weighty, right? If you think that this is their attempt to translate and that then they go on to claim that they got it right and that that was the source material for the Book of Abraham itself that we got in our scriptures, that’s how it gets all convoluted and loaded, right? And so—

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yep.

Scott Woodward: —none of those assumptions are actually baked in, right? You have to bring those assumptions to it. So that’s the Kirtland Egyptian paper controversy in a nutshell, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yep. That is a controversy. Admittedly, it’s a smaller, more minor controversy for the Book of Abraham, but it’s there. We wanted you to know.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Now let’s get to the main course, which is the facsimiles from the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward: Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Scott, bring us up to date on the facsimiles and where we’re at and what we’re going to be dealing with today.

Scott Woodward: Okay, yeah. So there are major controversies in the Book of Abraham regarding these facsimiles. There’s three. We’ve all known them since childhood. If you grew up as a child in the Latter-day Saint movement, you know that in the back of your scriptures, there’s these three pictures, and they’re called Facsimile 1, Facsimile 2, Facsimile 3. We’ve already introduced in our last episode some of the controversies regarding these. The first one was that nothing in the existing papyri that is right next to, for instance, Facsimile 1, corresponds to anything in Joseph’s Book of Abraham translation: that there’s nothing about Abraham in the hieroglyphs that are right next to Facsimile 1, if you go look that up on Joseph Smith Papers. And we’ve dealt with that. That’s not a problem. That’s not an issue. Joseph Smith never claimed to be translating, and none of the eyewitnesses say he was translating, from Facsimile 1, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: But Facsimile 1 does end up in our scriptures without the hieroglyphs next to it on the right hand side, and so it has something to do with Abraham, doesn’t it? In fact, the little descriptions underneath say that it’s about Abraham, that it’s Abraham on an altar, right? And then the story is told in Abraham chapter 1 about how his father attempted to sacrifice him through one of the priests of Elkenah, I believe he said it was.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: But with Facsimile 1, when you look at it a little more carefully, what we find is that the head of the priest that’s trying to sacrifice the guy on the altar is missing, and part of the torso of the guy is missing, and modern Egyptologists look at that and say, Oh, the priest, that’s obvious who that priest guy is that’s standing by the bed. That’s a typical Egyptian embalming scene. These are all over Egypt. If you go to Egypt today, you can see these. This has nothing to do with Abraham or human sacrifice: That’s the God Anubis. He’s just embalming somebody. There’s little jars underneath the bed where they would take out the organs and place them in there. And Anubis is, like, a—he’s actually a jackal-headed god, and you can see in Egypt these types of facsimiles, and they always with the person lying on the couch, have Anubis, the jackal-headed god, standing above them, embalming them.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: This is an embalming scene. This is not Abraham being sacrificed, according to modern Egyptologists.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: So that’s a problem with Facsimile 1. Facsimile 2 is the circle, little disc. It’s called a hypocephalus. Hypo just means under, and cephalus means the head. This is a little disc, usually made out of papyrus or stuccoed linen or bronze or gold or wood or clay, which Egyptians would carve these hieroglyphs in, and then they’d place it under the head of their dead. And they believed what was carved on that disc would magically cause the head and body to be enveloped in flames or radiance, making them divine, and the hypocephalus itself symbolized the Eye of Ra, or Horus, which is the sun god, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: And the scenes that are portrayed on the disc then relate to the Egyptian concept of resurrection and life after death, that kind of thing. Sometimes it was thought that the disc would be like a guide into the afterworld, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Like a map of the afterlife or something like that.

Scott Woodward: Yeah, a map of the afterlife, that’s right. But I think the key idea is that the disc itself, like if you zoom out, that’s, like, the eye of Ra. You zoom in, and it’s got, like, the details of the map to the afterlife, and the concept of resurrection, etc. So that’s the hypocephalus, and it has nothing to do with Abraham. This is just a disc to guide the dead, placed under their head. And then the third facsimile is a drawing of a judgment scene from the 125th chapter of the Book of the Dead. And it has, again, nothing to do with Abraham, inherently. This was not about Abraham. This is a judgment scene. You can see these people. There’s someone sitting on a throne, there’s someone standing behind that person, and there’s three people in front of the judgment seat. Two of them are holding hands, and one person behind is holding on to the waist of the person. I don’t know if they’re pushing them forward or what. You can interpret how you will. But Facsimile 3 is really fascinating because it has a lot of hieroglyphics still on it. Even in our scriptures, if you go look there, you can see these hieroglyphics, and then you see these little numbers, and those numbers then correspond to English at the bottom. We presume, there’s another assumption we have to make, but we assume that the interpretations of those hieroglyphs are Joseph Smith’s. At least they have his approval, as they were printed in the Times and Seasons.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Which, by the way, the Book of Abraham doesn’t become scripture canon for Latter-day Saints until 1880. So long after Joseph Smith’s dead, but he obviously endorsed the Book of Abraham. He published it. He thought it was super important.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: And that’s how far it went in his lifetime. But later the significance of it is recognized by church leaders to the point of suggesting it for canonization, and it makes it into our canon. So now we have canonized facsimiles, canonized Egyptian facsimiles, which appear to have nothing to actually do with Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: And especially that third facsimile with Joseph Smith, ostensibly his interpretation or translation of the hieroglyphs, that has nothing to do with Abraham. He says it does, but when modern Egyptologists look at those hieroglyphs, they say that Joseph got it wrong, that his translation is not accurate. So to say it succinctly, the translations of the facsimiles that we do have in our scriptures right now, that are canonized, are actually way off according to modern Egyptologists. And so that’s the major controversy we want to talk about today, because some people look at that and say, that’s checkmate. That’s game over for Joseph Smith. We finally have a way to assess Joseph’s ability to truly translate, because he always claims to be able to, and now we can test him, and he fails the test. And so, boom. Game over. So what do we do with that, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Today we want to talk about what faithful Egyptologists, Latter-day Saints, have to say about that in response to that criticism. Like, Kerry Muhlestein, he’s got a degree from UCLA, right Casey?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yes. He was named the graduate student of the year at UCLA in his PhD program.

Scott Woodward: Which is in Egyptology, correct?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yes, that is correct, yeah.

Scott Woodward: And other scholars that are full-on believers that Joseph Smith is a true prophet, who also not only know about these controversies, but actually can read the hieroglyphs, and they know a whole lot more. This is an example of where a little learning is a dangerous thing. Saying, “Ooh, Egyptologists, they say that Joseph Smith got that wrong, therefore, boom. Checkmate, Joseph Smith.” A little bit of learning here is dangerous.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: What we need to do is drink deeper. We need to go deeper, drink deeper, get into the Egyptologist mindset.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: In fact, today we’re going to let Kerry Muhlestein be our guide. I called him once about this particular issue, and I said, “Kerry, you’ve studied this. You’re aware of the controversy, and yet you’re still a believer that Joseph Smith is a true prophet and that the Book of Abraham is true scripture. How do you reconcile all that? Like, what do you do? Walk me through the mental moves,” right? And, “What do you know that some people don’t know? That the ones who don’t know it and are struggling with this and say that this is, like, one of the linchpins that broke their testimony? Like, what do you know that keeps you in, whereas others are more vulnerable because they don’t know what you know? Like, tell me what you know, Kerry.” And he’s very gracious. He’s a super kind, gentle man. He said, “I can give you a short version, but Scott, I’ve published about this. Haven’t you read my stuff?” Like, “Ah, crud.” and he actually sent me a link to one of his articles that he’s written about this in the Meridian Magazine in September 2014. It’s called, “Interpreting the Abraham Facsimiles.” Super helpful. And so let me just walk through what Kerry says. I’ll quote from his article, and we can discuss as we go through this. So this is in direct response, then, to that controversy about, did Joseph Smith actually get the translation wrong? And do these facsimiles even belong in our scriptures if they weren’t originally even about Abraham, and do they in any way cast a negative light on Joseph Smith’s prophethood? So, anything you want to say, Casey, before I walk through?

Casey Paul Griffiths: No, fire away. Just that I know all these guys, too, and I trust them, and their scholarship in here is really interesting, too, so let’s dive in.

Scott Woodward: Okay. Here we go. So here’s what Kerry says: He says, “Even though it is obvious to ask whether or not Joseph Smith’s explanations of the facsimiles matches with those of Egyptologists, it is not necessarily the right question to ask.” Ah, shoot, comes out swinging here. “As we compare Facsimile 1,” he continues, “or any of the facsimiles, with similar Egyptian vignettes, we may be barking up the wrong tree.” He goes on, “What if Abraham’s descendants, the Jews, took Egyptian elements of culture and applied their own meanings to them?” Let’s pause and just soak that in for a second. “What if Abraham’s descendants, the Jews, took Egyptian elements of culture and applied their own meanings to them?” So a cultural appropriation of Egyptian artifacts into Jewish ways of thinking. This is interesting. He goes on, “We actually know this happened, so we shouldn’t be looking at what Egyptians thought facsimiles meant at all, but rather at how ancient Jews would have interpreted them. The facsimiles were created in a day when the Egyptians were living among a great number of Greeks and Jews, and each of these cultures borrowed from each other,” he says.

Casey Paul Griffiths: That’s an interesting thing that he actually starts his little book on the Book of Abraham with, is that in Egypt, where Hor, who’s one of the figures associated with these papyri—there were tons of Jewish people living there.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Kind of like a little subculture, the way you might have, like, a, you know, a little Guatemala, you know, or a little Cuba or anything like that. Like, the way he’s describing Alexandria reminded me a lot of when I was a missionary in Miami when there was, like, a little Nicaragua and a little Cuba and a little Trinidad over here and a little Jamaica and all these subcultures mingling together because it’s a commercial and intellectual center. In fact, Alexandria is the, you know, intellectual center of the early ancient world.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And that’s where a lot of these manuscripts come from. So it does fit that whoever the owner of these papyri were, which we think is Hor, that Egyptian priests would be interacting with all these different cultures. That’s something that works.

Scott Woodward: Yeah. In fact, one of the articles at Pearl of Great Price Central says this: that “the city of Alexandria was home to a sizable Jewish community.” We’re talking from about 300 BC to 400 AD. “And evidence from surviving textual sources confirms that Jewish names, including names like Solomon, Aaron, Abraham, and Samuel proliferated throughout Egypt.” So obviously the Jewish culture is influencing Egypt, and the Jews are being influenced by Egypt during this time.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: “There is also clear evidence,” I’m continuing to quote from that Pearl of Great Price Central article. “There is also clear evidence that these Egyptian Jews copied their sacred texts and composed new texts while they lived in Egypt. The Old Testament was translated into Greek in Alexandria during this time. And,” key point, “stories about Abraham and other Biblical figures circulated amongst Jews living both inside and outside of Egypt.” And the Jews actually established a thriving community on the island of Elephantine, and they actually build a temple to Yahweh there, to Jehovah, the God of Israel. And they made copies of biblical texts that have survived today, again, attesting to the existence of a thriving literary and religious culture in their community. So, yeah, this is not a small point. This is a big point. This is where context is going to play a huge role in helping to mitigate the potency of that attack against Joseph Smith and the Book of Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: So Kerry Muhlestein continues. He says, “The Greeks were heavily influenced by the Egyptians, and the Egyptians borrowed from both the Jews and the Greeks in their religious and cultic practices and representations. And many Jews were similarly influenced by the Greeks and Egyptians.” This is cultural sharing and borrowing from each other and influencing one another. And so he says, “The Jews in Egypt were using representations from the cultures around them, but using and understanding them in their own unique way. Isn’t it possible that this was also done with all three facsimiles? Couldn’t these all represent a Jewish way of understanding Egyptian style drawings?” And then he says, “On the other hand, we also know that at least some Egyptians were using Jewish stories and ideas in their religious practices and writings.” And so here’s his conclusion: “Given this cross-cultural sharing and using each other’s depictions and names and stories, how can someone forcibly argue that something like Facsimile 1 cannot represent something other than the traditional Egyptological interpretation? Such a supposition is untenable and would never be made unless an agenda was driving it. This is especially so when we examine all the unique elements behind Facsimile 1.” So, ooh, that’s a lot. That’s an important nugget that he’s giving us here. This idea of cross-cultural sharing and using one another’s art and stories is huge.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: So let’s think about this slowly, here. Let’s think through some of the options of what that kind of opens up for us in terms of ways of thinking about the facsimiles.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Okay.

Scott Woodward: So at level one you have what the original Egyptian author or artist was trying to depict in the facsimile, right? But then you’ve got layer number two, or level number two, is what Jews who are living in Egypt thought those pictures meant or adapted those Egyptian depictions to say, what stories they wanted those depictions to tell that diverged significantly from the original meaning of the original artist, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: And then you’ve got level three, which is you’ve got Egyptian priests—specifically in Thebes, by the way, in the very area where these mummies and papyri scrolls were discovered that end up being, at least one of them, part of the Book of Abraham. It’s from that same area. We’ve got Egyptian priests in Thebes who are incorporating Jewish stories about Abraham into their Egyptian worship. So we know this is actually happening in the right place and at the right time where those same scrolls were discovered that are the source material for Facsimiles 1, 2, and 3 that we have in our scriptures now. So let’s just take a breath for a second and think about what that means and the possibilities that opens up. Anything you want to say about this so far, Casey?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Just that, like I said, the situation, inevitably, is more complex than just, hey, Joseph Smith got this Egyptian symbol wrong. Symbols are really complicated. Like you said, sometimes in the cultural context—like, if you see the St. Louis Temple, it’s got a big Star of David in the big, blue window that’s there. We always associate that symbol with Judaism, but Latter-day Saints can take that symbol, too—I mean, it’s really just an upward triangle and a downward triangle superimposed over each other—and give a different meaning. And so in a situation where we’re dealing with symbols, there’s a lot of ways to interpret it. And actually, like Kerry’s saying, it seems like in antiquity, this was something that happened quite a bit.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Symbols being repurposed to tell different stories.

Scott Woodward: Cultural appropriation is sometimes what it’s called today. Take one thing from one culture, bring it into your culture, and you can give it a twist and a different meaning than it originally meant in its original culture, and that’s just what humans do.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah. And cultural appropriation is generally seen as negative today.

Scott Woodward: Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths: In the ancient world, not really. I mean—

Scott Woodward: Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths: It happened all the time, and it was not seen as stealing anything.

Scott Woodward: Right, exactly. And being aware of that totally opens this up for us. So that’s the intellectual groundwork that needs to be laid, and you need to have that mindset so that you can appreciate what we now find in the actual archaeological record from Thebes at this time. Check this out. So two papyri have been discovered in Thebes, that same part of Egypt as Joseph’s papyri, in the early 1800s that date to around the 3rd century AD, roughly the same age as Joseph Smith’s papyri, and they are talking about, guess who? Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: In fact, there’s a lion couch scene, actually, very similar to Facsimile 1, a lion couch scene that was discovered in Thebes from the same time period, late 200 AD-ish, that appears in, it’s called the Leiden Papyrus. And so you’ve got the lion couch, you’ve got someone laying on it, and then above them is Anubis, the jackal-headed god, and there’s little writing underneath it, in Greek, by the way. In Greek is written Abraham’s name. It says something like, “Abraham, who upon,” and then the papyrus cuts off right there, so we’re not sure what it said, probably something like, “who upon the couch.” It’s one of our best evidences that what Kerry is telling us here is actually happening. We’ve got lion couch. It’s Egyptian. It’s in Thebes, but we’ve got Greek writing underneath it, and it’s associating it directly with Abraham, right? I don’t know if you can get more of a bullseye than that, actually.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: That’s super helpful. Did the original artist think that was about Abraham? Who knows? But what matters is that by 200 AD, there is someone who speaks Greek who is associating this lion couch scene with Abraham. That’s what matters.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Now let’s talk about the hypocephalus, Facsimile number 2. So we talked about how that represents the Eye of Ra or the Eye of Horus, right? The Sun God. Sometimes they call it the Wedjat Eye. This is the Wedjat Eye. Maybe you’ve seen, there’s that kind of classic Egyptian eye painting. It’s like an eye, and it has, like, a nice eyebrow above it, and there’s, like, this little swirly thing that comes down from the bottom of the eye. You know what I’m talking about?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, these are all over Egypt.

Scott Woodward: Yeah, these are called the Wedjat Eye.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Yeah. And the pupil of the eye is representation here of, this is Horus, this is Horus’s eye. Now why that matters is because there was discovered, again, about late 200 AD-ish, from the Thebes area, on a second papyri, the phrase, “Abraham, the pupil of the eye of the Wedjat.” Woo! “Abraham, the pupil of the eye of the Wedjat.” And what does the hypocephalus represent? It represents the pupil of the eye of Horus, which is the Wedjat Eye.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: So, boom, there we go. So now we’ve got two ancient Egyptian papyri that Joseph Smith could not possibly have known about that associate Abraham not only with a lion couch scene, but now also with the Wedjat Eye of Horus, which the hypocephalus is supposed to represent. So far, that’s two for two, Casey. That’s two for two. The right time, the right location, and superimposing Abraham onto these more ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, right? Associating Abraham with the meaning of these.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Again, whether that was the original intention of the original artist or not doesn’t matter at all, right? What matters is that we’ve now got solid evidence that people at this time and in this place were using Egyptian facsimiles to tell stories about Abraham, which is no more or less than what Joseph Smith is claiming with the three facsimiles in the Book of Abraham, correct?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: So what about Facsimile number 3? That judgment scene from the 125th chapter of the Book of the Dead. What about that one?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Well, there was something called the Testament of Abraham that was discovered after Joseph Smith’s time where Abraham is shown a vision of the last judgment scene that is unquestionably related to the judgment scene pictured in the 125th chapter of the Book of the Dead. Thus clearly associating, again, Abraham with the Egyptian Book of the Dead. That’s three for three, Casey.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: That’s three for three, where Facsimile 1, Facsimile 2, and Facsimile 3 are all associated, in antiquity, in Egypt, with Abraham. And at least two of those three are from the Thebes area.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Woo! What do you want to say about that?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Just that all this is a great example of what you’ve referenced several times, which is to think slowly about things.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: A lot of times, when somebody says something like, “Hey, Joseph Smith’s interpretation doesn’t match what Egyptologists say,” somebody just jumps off the boat, you know, and uses it as an excuse to disassemble their whole belief system, and we all need to reevaluate our beliefs from time to time. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Scott Woodward: Sure.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But at the same time, too, when something new and shiny comes along, it doesn’t mean you have to abandon everything that you’ve already believed.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: And let me give you another example, and this is one that Kerry often cites in regards to Facsimile 1. Facsimile 1 is depicted as the priest attempting to sacrifice Abraham, and a lot of Egyptologists really had an issue with that because Egyptians didn’t practice human sacrifice. So they felt like, you know, this is an obvious error or falsity because Egyptians don’t practice human sacrifice.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: That was the prevailing thought of the day when Kerry Muhlestein started doing his work, and it turns out that it’s wrong.

Scott Woodward: Ooh.

Casey Paul Griffiths: There were situations where Egyptians did practice human sacrifice.

Scott Woodward: Ah, shoot.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But here’s the condition: human sacrifice typically happened for what is called a cultic offense, or an offense against the Egyptian god. So they did practice human sacrifice, but typically when it was carried out was when somebody was, you know, blaspheming against the gods. So what does the scenario in the Book of Abraham present? That Abraham is doing exactly that. Abraham is saying these gods are false and they’re idolatrous and we shouldn’t worship them. And so they attempt to take his life because of it.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: The other thing is is the Book of Abraham clearly presents Ur, the place where Abraham grows up, as an Egyptian satellite community. Did this sort of thing, these cultic sacrifices, when someone’s blaspheming against the god, happen in these satellite communities? Yeah. So that’s one case where the prevailing thought of the day was Egyptians don’t do human sacrifice. Then, as more evidence, as more materials came forward, it turns out, yeah, they do. And they did precisely in the kinds of circumstances that the Book of Abraham describes. Now, if you had just taken that “Egyptians don’t practice human sacrifice” idea and run with it, you could have made a huge mistake. On the other hand, if you look at it and say, “All right. It seems like that conflicts right now, but I’m not going to panic or anything like that,” eventually the evidence came forward that not only confirmed that the Book of Abraham and Facsimile 1 and the scene presented are plausible, but that they actually fit the newer facts that we know quite well. And so you’ve done a great job here, Scott, illustrating the practice we advise to people, which is to think slowly about things. You know, don’t run off with a single idea just because it seems to conflict with what you believe.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Take time to think about it, and it’s okay to reevaluate from time to time, but also don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, where you completely abandon everything because something appears to conflict and you can’t handle it.

Scott Woodward: I like to say don’t draw thick conclusions from thin evidence. The facts are there are some Egyptologists who say that Joseph Smith got it wrong. And that’s the facts. That’s pretty thin. That’s a pretty thin fact on which to base your beliefs about the Book of Abraham specifically, it’s a pretty thin fact on which to base your beliefs about Joseph Smith’s claims to prophethood generally, and that’s a pretty thin fact on which to base whether or not to abandon your covenants ultimately.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Right? Let’s work on that. Let’s think slowly through that. That’s interesting. What else has been said? What else do we know, right? Let’s dig deeper. Let’s go into all of it, because I know there’s believing members of the church who know all this stuff. There are believing Egyptologists in the church that are not rattled by this. Why not? Let me go deeper. Let’s find out why.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: And I’ve found, as I’ve done that, as I’ve thought slowly about this, that it always leads to some sort of satisfying resolution. That doesn’t mean I don’t have questions, still. It doesn’t mean that I’m not waiting for further light and knowledge on some things, but there’s never been anything that I’ve found, like this, that seems like a “Checkmate, Joseph Smith,” right? “You’re done, brother.” There’s nothing that, under further study and research and scrutiny and scholarship, doesn’t eventually resolve in a pretty satisfying way, like we’ve seen with this today.

Casey Paul Griffiths: So keep calm, and carry on. Is that the basic message we’re going for here?

Scott Woodward: Man, we should put that on a mug. As we study church history, just sip your Ovaltine from that mug that says, “Keep calm, carry on, think slow, don’t draw thick conclusions from thin evidence, and let’s continue to stay the course.” Yeah, so that’s been helpful for me. That’s pretty satisfying for me, in addition to all the different little evidences for the Book of Abraham, right? That, things like you just said, like Ur, like human sacrifice, like there’s a little crocodile on Facsimile 1 underneath the jars 8 and 7. The crocodile is numbered number 9, and it says that it’s associated with Pharaoh. Nobody in Joseph Smith’s day thought the crocodile was associated with Pharaoh. But later on we find that the crocodile is associated with Pharaoh. Just tiny, little things like that, right? Or on Facsimile 2, there’s these four individuals, they’re called the Four Sons of Horus, that represent the four points of the compass, which is what Joseph Smith says that they meant. And that’s interesting, right? That’s like, oh, he got that right. There’s the geocentric view of the universe rather than, like, the Sun-centered view of the universe. The geocentric view of the universe is how Abraham depicts things, and that was consistent with Abraham’s time, not Joseph Smith’s time. Kerry makes a big deal about the plains of Olishem. In Abraham chapter 1 verse 10, Abraham mentions the Plain of Olishem. There is no biblical equivalent to the Plain of Olishem. That phrase, however, has since been discovered in two translations of ancient texts after the Book of Abraham was published, the Plains of Olishem, and associating that with Abraham and during this time period. There’s a bunch of things like that, right? Like, ancient tradition that Abraham taught astronomy and sciences to Egyptian priests. That’s not in the Bible, but later on we find out about that, and that’s, again, post-Joseph Smith translating this. So there’s, like, a hundred of those little things, and there’s a ton of little articles like that on Pearl of Great Price Central that you can go check out.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Those aren’t what do it for me. Those don’t, like, prove to me that this is true scripture, but they’re helpful. I like those. But then when I read the book, like, it’s light. It’s good. It’s beautiful. It’s inspiring. And so there’s multi layers to why I believe the Book of Abraham is authentic scripture, and they all work together for me to strengthen my testimony.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah, these arguments help towards plausibility. Like, is it plausible the Book of Abraham is an ancient document? I think it totally is.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But when it comes to testimony, when it comes to your belief in these things, it’s a lot like the Book of Mormon, where, you know, the greatest witness comes from the Holy Ghost.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: But these plausibility arguments are helpful when it comes down to it, too, because, again, those two things that we’ve talked about: reason and faith. “By study and also by faith,” the Lord in the Doctrine and Covenants constantly refers to those as two major tools that you use. And sometimes the study part of your brain needs a workout. Sometimes the faith part of your brain needs a workout, too. You use them two together.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Like I said, on Pearl of Great Price Central, there is a ton of good stuff to help you. Like, I’m going to refer to one article really quick, which was, were there autobiographies like this in the ancient world when Joseph Smith published the Book of Abraham when it was canonized? And the answer was, no, we don’t really have any other examples like this. However, in 1939, a document was discovered that is a kind of autobiography. It’s about a guy who lived in the general vicinity, Middle East and ancient Syria, around the time that Abraham lived, the guy’s name is Idrimi. I hope I’m saying that right. I-D-R-I-M-I, Idrimi, and it lines up pretty well with Abraham’s autobiography himself. For instance, they both talk about going on journeys. They both talk about God leading them to a new homeland. They both talk about promises made to their ancestors. They both describe covenants that God made with them. In fact, the opening of the Book of Abraham is “In the land of the Chaldeans, at the residence of my father’s, I, Abraham, saw it was needful for me to obtain another place of residence.” The opening line of Edrimi’s autobiography is, “In Aleppo, my ancestral home, I, Edrimi, the son of Elim, Elimia, took my horse, chariot, and groom, and went away.” They even have similar openings.

Scott Woodward: Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths: This document wasn’t discovered until 1939, a century after the Book of Abraham. So that’s just one of many plausibility arguments we have to say, is this plausible? Yeah.

Scott Woodward: Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Can you gain a witness that it’s true just through plausibility arguments? That’s not how anything works. You have to gain a spiritual witness alongside your secular witness to know if this is true. And just like you said, there’s some beautiful, beautiful teachings in the Book of Abraham that make it incredibly valuable to our understanding of the universe, of God, and of our relationship to God, I think are worth exploring.

Scott Woodward: We have a former president of BYU–Idaho, Henry J. Eyring, son of Henry B. Eyring. He told me this story once, personally. He said that at a certain time of his life, when some of this criticism about the Book of Abraham was coming out, and he was wrestling with it, the facsimile problems we’ve highlighted today, and his dad was in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and so he reached out to his dad, and they talked about it. He laid out all of his concerns, you know, “What about this? And what about that?” And his dad listened patiently, and then he said, “Henry, how do you feel when you read the Book of Abraham?” And Henry said, “I feel good.” And Elder Eyring said, “Me, too.” And then he said, “How’s your family?” How are things going? You know, just kind of changes the subject, like, as if to say, that’s enough, isn’t it? You’re like me. You can discern the goodness and the truth and the light in the Book of Abraham, right? I love that. I kind of envy that, actually, a little bit, because I think there’s some people that are totally okay with that much, to say, “Hey, I feel good about the Book of Abraham. I don’t need to get into all these arguments. Like, I know it’s scripture. End of story.” And I actually envy that. I’m not one of those, but I think that’s super cool that some people are just, like, not bothered by any of this stuff, and that’s beautiful, and their testimony’s strong, and they keep their covenants, and I think they’re going to be just fine. But then there’s other people, like me, that, like, get all caught up with this kind of stuff. And I think the Lord was talking about people like me when he said in D&C 88:118, He says, “and as all have not faith, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom. Seek learning, even by study and also by faith.” That the antidote to not having faith is to seek learning by study, but also never forget that faith component. Like, I feel like there’s something in my soul that needs scholarship, that needs well-researched answers. And that could be a weakness. I don’t know. D&C 118 seems to say that not everybody has this implicit faith. Not everybody can just say, “I feel good about this.” And the Lord’s okay with that. He just says, no problem. “Seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom. Seek learning, even by study and also by faith.” So, add to your lack of implicit faith some study. And I just say to those who are in a position like me that kind of need this scholarship, like, wonderful. Go after it. Dig into it. Make sure you’re getting really solid answers from those who can actually answer the questions really well. But never forget that other piece. It always needs to be study and faith. Never let go of that faith piece.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: In fact, let me just use the Book of Abraham to give you an example of what I mean about holding both of these together at the same time. Study and faith. Reason and revelation. So let’s do study first. Here’s a cool little piece of scholarship. The word shinehah shows up in the Book of Abraham, and that word is associated with the sun and its path across the sky, which recent research has revealed was actually an ancient Egyptian word that was used only in Abraham’s day to describe the sun on its path. That’s cool scholarship. Like, I actually like that a lot.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: And I’m going to put that next to what President Eyring said. Like, I feel good, too, when I read the Book of Abraham. I feel good, and scholarship is strengthening the case of the plausibility of the historicity of the Book of Abraham. Like, both of those are really helpful, and, for me, needful. Some of us need both reason and revelation, both the scholarship piece and the undeniable feeling that this is good and I want to be a better man because of what I’m reading, you know?

Casey Paul Griffiths: Yeah.

Scott Woodward: And, again, I just say for people that are kind of in my boat, don’t let go of that second piece. Like, go get all the scholarship you can, but make sure that faith is always part of the equation.

Casey Paul Griffiths: Amen.

Scott Woodward: So I think at the end of the day, I like how the Gospel Topics essay lands the plane on this, and maybe we can end with this today. “The veracity and value of the Book of Abraham cannot be settled by scholarly debate concerning the book’s translation and historicity. The book’s status as scripture lies in the eternal truths it teaches and the powerful spirit it conveys.”

Casey Paul Griffiths: Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward: “The Book of Abraham imparts profound truths about the nature of God, his relationship to us as his children, and the purpose of this mortal life. The truth of the Book of Abraham is ultimately found through careful study of its teachings, sincere prayer, and the confirmation of the spirit.”

Casey Paul Griffiths: Wonderful. This has been great, Scott. Thank you so much for your good work, and thanks to all the great scholars out there who we steal from on a weekly basis, and thanks to you for hanging in there with us as we go through each one of these subjects. Again, we want to point you towards Pearl of Great Price Central, where there’s a ton of good stuff, and also Doctrine & Covenants Central and just Scripture Central in general, where you’ll find a lot of good materials, articles, videos, and other resources that you can use in your study of the scriptures as you seek to understand, defend, and interpret the scriptures more accurately.

Scott Woodward: Thanks, Casey. Thank you for listening to this episode of Church History Matters. To dig deeper into what we discussed today, we recommend beginning with several excellent short articles on pearlofgreatpricecentral.org. In our next episode, we’ll take a brief pause from the controversies of the Book of Abraham and dive into what makes it beautiful, what makes its teachings important, and why it’s a critical part of the Latter-day Saint canon. If you’re enjoying Church History Matters, we’d appreciate it if you could take a moment to subscribe, rate, review, and comment on the podcast. That makes us easier to find. Today’s episode was produced by Scott Woodward and edited by Nick Galieti and Scott Woodward, with show notes and transcript by Gabe Davis. Church History Matters is a podcast of Scripture Central, a nonprofit which exists to help build enduring faith in Jesus Christ by making Latter-day Saint scripture and church history accessible, comprehensible, and defensible to people everywhere. For more resources to enhance your gospel study, go to scripturecentral.org, where everything is available for free because of the generous donations of people like you. And while we try very hard to be historically and doctrinally accurate in what we say on this podcast, please remember that all views expressed in this and every episode are our views alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of Scripture Central or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Thank you so much for being a part of this with us.

Show produced by Scott Woodward, edited by Nick Galieti and Scott Woodward, with show notes by Gabe Davis.

Church History Matters is a podcast of Scripture Central. For more resources to enhance your gospel study go to scripturecentral.org, where everything is available for free because of the generous donations of people like you.