Blacks and Priesthood/Temple Ban Timeline

Introduction: The history surrounding the priesthood and temple restriction on those of African descent in the Church is perhaps best understood in three phases: Phase 1: Priesthood and Temples Available to All (1830-1852), Phase 2: Priesthood and Temple Ban in Effect (1852-1978), and Phase 3: Priesthood and Temples Available to All Again (1978-Present). Additionally, it is vital in seeking an accurate understanding of history—particularly this history—that statements and actions of individuals are understood in their proper contexts, otherwise misunderstanding is certain. Hence, throughout the following timeline the record of actions and statements will often be preceded by a contextual preface indicated in yellow.

Table of Contents (for Quick Access)

PHASE 1: PRIESTHOOD AND TEMPLES AVAILABLE TO ALL (1830-1852)

GENERAL HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THIS ERA

Black African slavery as a legal institution was an established norm in several states in the Union. This was a highly fraught and contentious issue among many throughout the US which eventually culminated in the Civil War in 1861-1865. Views on slavery at this time varied widely. Those who accepted it, supported it, and built their economy on it were on one far end of the spectrum, while those who opposed it and agitated for the immediate and total abolition of slavery were on the other.

These “abolitionists,” as they were known, were considered extremists and radicals by a large segment of society. Those more moderate in their antislavery position, such as Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, advocated for the gradual ending of slavery (source). Everyone’s views on slavery fell somewhere on this spectrum.

Though slavery views varied widely, there was a more broadly shared belief among most whites of the time that blacks were somehow inherently inferior to whites. Many believed this could be proven by simple observation or scientifically. Thomas Jefferson, himself a slave owner and scientist, cautiously concluded after his own observations in 1781 that blacks were “inferior to the whites in the endowments of body and mind” (source). Scientists, zoologists, physicians, and philosophers from the 17th to 19th centuries concluded variously that blacks were biologically less advanced than whites, had smaller brains, were a separate species more closely related to monkeys or apes, or had greatly degenerated from the originally pure race of Adam and Eve, which, of course, was white (source). All of this explained in a twisted kind of logic why blacks were less intelligent than whites (smaller brains), felt less pain and emotion (more primitive nervous systems), and generally lacked sexual restraint (more closely related to animals). These pseudoscientific explanations allowed many whites to accept their superiority to blacks, not as a matter of bigotry, but as a simple matter of logical fact. Hence, “racial distinctions and prejudice were not just common but customary among white Americans” (source). It can be understood then, why intermarriage or sexual relations between whites and blacks (called “amalgamation” or “miscegenation”) was not only frowned upon during this time, but legislated against in many states (source). Respected physicians in the mid-1800s warned that the offspring of mixed-race couples would be weak and infertile and would probably, therefore, lead to the destruction of both races (source).

Against this backdrop we can better understand how the US Congress could, in 1790, limit citizenship to “free white persons” (source), how the U.S. Supreme Court could declare in 1857 that blacks were “beings of an inferior order … and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect” (source), and how Abraham Lincoln—the great emancipator—could say in 1858:

I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people. I as much as any man am in favor of the superior position assigned to the white race. (source)

These views and realities, “though unfamiliar and disturbing today, influenced all aspects of people’s lives, including their religion” (source). In fact, to biblically justify the practice of slavery many in early Protestant America (as early as 1730) taught that “blacks descended from the same lineage as the biblical Cain, who slew his brother Abel. Those who accepted this view believed that God’s ‘curse’ on Cain was the mark of a dark skin” (source). The “curse of Ham” from Genesis 9 was also used to justify slavery and to further affirm the inferiority of blacks to whites. According to this story, “Ham discovered his father Noah drunk and naked in his tent, but instead of honoring his father by covering his nakedness, he ran and told his brothers about it. Because of this, Noah cursed Ham’s son, Canaan by saying that he was to be ‘a servant of servants’ (Genesis 9:20-27). One interpretation of this passage states that Ham married a descendant of Cain. While there is no indication in the Bible of Ham’s wife descending from Cain, this interpretation was used to justify slavery and it was particularly popular in North America during the Atlantic slave trade” (source). Thus slavery “was sometimes viewed as a second curse placed upon Noah’s grandson Canaan as a result of Ham’s indiscretion toward his father” (source). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in 1830 “during the height of Protestant acceptance of the curse of Cain doctrine in North America, as well as the even more popular curse of Ham doctrine” (source). Many converts carried such ideas with them into the Church.

Timeline of Which States and Territories Admitted Slavery

Made by Golbez, Licensed under CC BY 3.0

1829

BOOK OF MORMON “ALL ARE ALIKE UNTO GOD”

June. Joseph Smith completes his translation of the Book of Mormon wherein the prophet Nephi wrote, “Behold, hath the Lord commanded any that they should not partake of his goodness? Behold I say unto you, Nay; but all men are privileged the one like unto the other, and none are forbidden…. [A]nd he inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile” (2 Nephi 26:28, 33).

1833

NO SPECIAL RULE AS TO PEOPLE OF COLOR

July. In regards to whether or not Church members who were “free people of color” should gather with the saints in Missouri (a slave state at the time), William W. Phelps advised in the Church’s newspaper: “So long as we have no special rule in the church, as to people of color, let prudence guide.” (“Free People of Color,” Evening and Morning Star 2, no. 14 (July 1833): 108)

JACKSON COUNTY LOCALS EXPEL THE SAINTS DUE PRIMARILY TO RACIAL FEARS

July-November. The non-LDS locals had a few grievances against Church members in Jackson County, Missouri, but their biggest grievance centered on their fears of the effect the Mormons would have on their slaves (Missouri was at this time a slave state).

They accused Church members of “tampering with our slaves … to sow dissentions and to raise seditions amongst them.”

They accused W.W. Phelps of using his newspaper to implicitly invite “free negroes and mulattoes from other states, to become Mormons, and remove and settle among us.” This they feared would be “one of the surest means of driving us from the county” since it “would corrupt our blacks, and instigate them to bloodshed.” It would also require them, the white locals, “to receive into the bosom of our families as fit companions for our wives and daughters, the degraded free negroes and mulattoes, who are now invited to settle among us. Under such a state of things,” they declared, “even our beautiful county would cease to be a desirable residence, and our situation intolerable” (source).

Thus, persecution raged against the Latter-day Saints at this time and they were ultimately expelled from Jackson County due in large part to the perception that they were too racially inclusive.

SLAVERY IS “NOT RIGHT”

December. In the aftermath of the saints being expelled from Jackson County, Joseph Smith receives D&C 101 wherein the Lord declares, among other things, that “… it is not right that any man should be in bondage one to another” (D&C 101:79).

1835

ALL CAN GET REDEMPTION

February. William W. Phelps writes in the Church newspaper, “All the families of the earth … should get redemption … in Christ Jesus,” regardless of “whether they are descendants of Shem, Ham, or Japeth” (“The Gospel. No. 5,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, Feb. 1835). Blacks at this time were believed by many Christians to be descendants of Ham.

D&C 134

August. In what was then called the “Declaration on Government and Law” and later published in the D&C, Church leaders declared, “… we do not believe it right to interfere with bond-servants, neither preach the gospel to, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters, nor to meddle with or influence them in the least to cause them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life, thereby jeopardizing the lives of men; such interference we believe to be unlawful and unjust, and dangerous to the peace of every government allowing human beings to be held in servitude” (D&C 134:12).

ALL PEOPLE ARE “ONE IN CHRIST”

September. William W. Phelps wrote that all people were “one in Christ Jesus … whether it was in Africa, Asia, or Europe.” (“The Ancient Order of Things,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, Sept. 1835)

1836

ELIJAH ABLE ORDAINED AN ELDER

January. Elijah Able (sometimes Ables) is ordained an Elder and his license is later endorsed by Joseph Smith, Jr. in March of this year (see Elijah Able’s License). Elijah was a black man (actually mixed-race, either 1/4 or 1/8 black African) and is the first recorded man with black African ancestry ordained an Elder in the Church (source).

JOSEPH SMITH LETTER TO OLIVER COWDERY ON ABOLITIONISM & SLAVERY

April. Contextual Preface: “One student at Oberlin [College], John W. Alvord, embarked on a lecture circuit [to spread abolitionism] in December 1835 that took him through various communities in northeastern Ohio, including … Kirtland…. According to the abolitionist newspaper Philanthropist, Alvord also lectured in Kirtland in April 1836 and organized a society there.

“The experiences of Latter-day Saints in Jackson County, Missouri, in 1833, as well as missionary efforts in the South from 1834 to 1836, … shaped the way in which Joseph Smith and other church leaders responded to the spread of abolitionism in Ohio…. On 18 July [1833], local [Missouri] residents circulated a document that decried church members as ‘deluded fanatics’ and accused them of ‘tampering with our slaves and endeavoring to sow dissensions & raise seditions among them.’… The perception that the church supported the migration of free blacks into Missouri ultimately contributed to the mass expulsion of church members from Jackson County. Violent opposition and a traumatic uprooting—felt collectively by church members from Missouri to Ohio—undoubtedly discouraged church leaders from actively engaging in issues of slavery and race from 1833 onward. In addition to their experiences in Missouri, successful missionary efforts in Tennessee and Kentucky from 1834 to 1836 likely made Joseph Smith and other leaders wary of openly supporting any antislavery movement that could potentially hinder proselytizing or ignite tensions between new converts and their Southern neighbors.

“These experiences, along with the spread of abolitionism in Ohio during the mid-1830s, compelled church leaders to periodically reiterate their views on slavery and emancipation. In distancing themselves from abolitionism, Mormon leaders were not alone in eschewing what was then considered a radical movement, even among those who regarded themselves as antislavery…. A 9 October 1835 editorial in the Northern Times (likely authored by Oliver Cowdery or Frederick G. Williams) informed readers that … ‘We are opposed to abolition, and whatever is calculated to disturb the peace and harmony of our Constitution and country,’ the editorial continued. ‘Abolition does hardly belong to law or religion, politics or gospel.’…

“John Alvord’s spring 1836 lecture in Kirtland likely prompted Joseph Smith to write the featured letter to Oliver Cowdery…. In his letter, Joseph Smith carefully outlined his position on slavery and emancipation. Joseph Smith’s views recorded here were expressed in response to a specific geographical, political, and cultural milieu. His ideas about black Americans and slavery were not static…. In the years after church members were expelled from Missouri and settled in Nauvoo, Illinois, Joseph Smith expressed a progressive view of the intellectual capacities of black slaves, advocated granting them certain civil rights, and, as a presidential candidate in 1844, campaigned for their emancipation.” (From JosephSmithPapers.org)

Joseph Smith letter to Oliver Cowdery: “Dear Sir—This place having recently been visited by a gentleman who advocated the principles or doctrines of those who are called abolitionists; if you deem the following reflections of any service, or think they will have a tendency to correct the opinions of the southern public, relative to the views and sentiments I believe, as an individual, and am able to say, from personal knowledge, are the feelings of others, you are at liberty to give them publicity in the columns of the Advocate [the Church newspaper]. I am prompted to this course in consequence, in one respect, of many elders having gone into the Southern States, besides, there now being many in that country who have already embraced the fulness of the gospel, as revealed through the book of Mormon…. Thinking, perhaps, that the sound might go out, that “an abolitionist” had held forth several times to this community, and that the public feeling was not aroused to create mobs or disturbances, leaving the impression that all he said was concurred in, and received as gospel and the word of salvation[,] I am happy to say, that no violence or breach of the public peace was attempted, so far from this, that all except a very few, attended to their own avocations and left the gentleman to hold forth his own arguments to nearly naked walls. I am aware, that many who profess to preach the gospel, complain against their brethren of the same faith, who reside in the south, and are ready to withdraw the hand of fellowship because they will not renounce the principle of slavery and raise their voice against every thing of the kind. This must be a tender point, and one which should call forth the candid reflection of all men and especially before they advance in an opposition calculated to lay waste the fall [sic] States of the South, and set loose, upon the world a community of people who might peradventure, overrun our country and violate the most sacred principles of human society, chastity and virtue. After having expressed myself so freely upon this subject, I do not doubt but those who have been forward in raising their voice against the South, will cry out against me as being uncharitable, unfeeling and unkind—wholly unacquainted with the gospel of Christ.

[Joseph now shares his personal belief below that slavery is biblical doctrine, citing Genesis 9:25-27, in something of a defense of Church members who believe and/or participate in slavery. Joseph admits that he does not understand God’s purposes and designs in allowing this practice, nevertheless he is clear in acknowledging that the enslavement of “the sons of Canaan” is in accord with the decrees and purposes of God.]

“It is my privilege then, to name certain passages from the bible [sic], and examine the teachings of the ancients upon this nature, as the fact is uncontrovertable, that the first mention we have of slavery is found in the holy bible, pronounced by a man who was perfect in his generation and walked with God. And so far from that prediction’s being averse from the mind of God it remains as a lasting monument of the decree of Jehovah, to the shame and confusion of all who have cried out against the South, in consequence of their holding the sons of Ham in servitude! ‘And he said cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem and Canaan shall be his servant.’—Gen. 9:25, 26, 27. Trace the history of the world from this notable event down to this day, and you will find the fulfilment of this singular prophecy. What could have been the design of the Almighty in this wonderful occurrence is not for me to say; but I can say that the curse is not yet taken off the sons of Canaan, neither will be until it is affected by as great power as caused it to come; and the people who interfere the least with the decrees and purposes of God in this matter, will come under the least condemnation before him; and those who are determined to pursue a course which shows an opposition and a feverish restlessness against the designs of the Lord, will learn, when perhaps it is too late for their own good, that God can do his own work without the aid of those who are not dictated by his counsel.” (Messenger and Advocate 2, no. 7 (April 1836): 288-91; see original at JosephSmithPapers.org)

ELIJAH ABEL ORDAINED A SEVENTY

December. Elijah Abel is ordained a Seventy by Zebedee Coultrin and becomes a “duly licensed minister of the Gospel” (Roll, First Council of the Seventy, December 27, 1836, CR 3 123, LDS Church History Library. Elijah had earlier this year also received his washings and anointings in the Kirtland Temple (source). Later in life, Zebedee Coltrin recalled resisting Joseph Smith’s directive to administer ritual washings and anointing to Elijah Ables; he said he complied only because he had been “commanded by the Prophet to do so” and told himself that he would “never again Anoint another person who had Negro blood in him.” (Coltrin qtd. in L. John Nuttall, Diary, May 31, 1879, typescript, Perry Special Collections. Quoted in (Stevenson, Russell W. For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism, 1830-2013. Greg Kofford Books. Kindle Edition). Coltrin is likely confusing ordaining Elijah a Seventy with administering the washing and anointing to him. But in either case, the statement from Zebedee shows his resistance to the idea of black equality.

Elijah Able Circa 1862-1873, photograph likely by Edward Martin. (Church History Library, Salt Lake City)

1840

“EVERY COLOR” CAN WORSHIP IN THE TEMPLE

October. The Saints at Nauvoo anticipated “persons of all languages, and of every tongue, and of every color; who shall with us worship the Lord of Hosts in his holy temple, and offer up their orisons in his sanctuary.” (“Report from the Presidency,” Times and Seasons, Oct. 1840)

1842

JOSEPH’S BLOOD BOILS OVER MISTREATMENT OF SLAVES

March. Joseph wrote in a letter “on the subject of American Slavery” that “it makes my blood boil within me to reflect upon the injustice, cruelty, and oppression, of the rulers of the people” in Missouri (ostensibly toward their slaves). He then said, “I fear for my beloved country.” (See letter at JosephSmithPapers.org)

SET SLAVES FREE, EDUCATE THEM, GIVE THEM EQUAL RIGHTS

December. In Joseph’s journal is recorded a conversation with Orson Hyde wherein Joseph said “he would not vote for a slave holder.” Orson asked what Joseph’s advice would be to a man who came into the church “having a hundred slaves.” Joseph responded, “I have always advised such to bring their slaves into a free country— & set them free— Educate them & give them equal rights.” (See entry at JosephSmithPapers.org)

1843

CHANGE THEIR SITUATION AND BLACKS WOULD BE LIKE WHITES

January. Joseph Smith’s Journal Entry: “At five went to Mr. Sollars’ with Elders Hyde and Richards. Elder Hyde inquired the situation of the negro. I replied, they came into the world slaves mentally and physically. Change their situation with the whites, and they would be like them. They have souls, and are subjects of salvation. Go into Cincinnati or any city, and find an educated negro, who rides in his carriage, and you will see a man who has risen by the powers of his own mind to his exalted state of respectability. The slaves in Washington are more refined than many in high places, and the black boys will take the shine off of many of those they brush and wait on. Elder Hyde remarked, ‘Put them on the level, and they will rise above me.’ I replied, if I raised you to be my equal, and then attempted to oppress you, would you not be indignant and try to rise above me?… Had I anything to do with the negro, I would confine them by strict law to their own species, and put them on a national equalization.” (See entry at JosephSmithPapers.org)

1844

JOSEPH’S ANTI-SLAVERY PRESIDENTIAL PLATFORM

February. Contextual Preface: On 29 January 1844 it was unanimously decided by Joseph and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles that Joseph would run for the presidency of the United States of America. A pamphlet of Joseph’s views was printed shortly thereafter entitled “General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States” wherein Joseph made clear he would be running on a strong anti-slavery platform. The relevant elements are quoted below.

“My cogitations, like Daniel’s, have for a long time troubled me, when I viewed the condition of men throughout the world, and more especially in this boasted realm, where the Declaration of Independence ‘holds these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;’ but at the same time some two or three millions of people are held as slaves for life, because the spirit in them is covered with a darker skin than ours….

“The wisdom which ought to characterize the freest, wisest, and most noble nation of the nineteenth century, should, like the sun in his meridian splendor, warm every object beneath its rays; and the main efforts of her officers, who are nothing more nor less than the servants of the people, ought to be directed to ameliorate the condition of all, black or white, bond or free; for the best of books says, ‘God hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.’

“Our common country presents to all men the same advantages, the facilities, the same prospects, the same honors, and the same rewards; and without hypocrisy, the Constitution, when it says, ‘We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America,’ meant just what it said without reference to color or condition, ad infinitum….

“Petition …, ye goodly inhabitants of the slave States, your legislators to abolish slavery by the year 1850, or now, and save the abolitionist from reproach and ruin, infamy and shame.

“Pray Congress to pay every man a reasonable price for his slaves out of the surplus revenue arising from the sale of public lands, and from the deduction of pay from the members of Congress.

“Break off the shackles from the poor black man, and hire him to labor like other human beings….

“The very name of ‘American’ is fraught with ‘friendship!’ Oh, then, create confidence, restore freedom, break down slavery, banish imprisonment for debt, and be in love, fellowship and peace with all the world!…

“With the highest esteem, I am a friend of virtue and of the people.”

JOSEPH SMITH.

NAUVOO, ILLINOIS.

February 7, 1844.

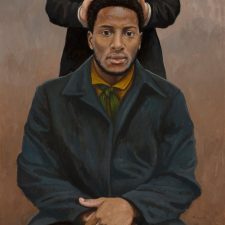

Q. WALKER LEWIS ORDAINED

Sometime This Year. Q. Walker Lewis, ordained an Elder by William Smith, brother of Joseph Smith and member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Lewis is the second black African American to be ordained to the priesthood. (Source)

The Ordination of Q. Walker Lewis

by Anthony Sweat

1845

ORSON HYDE LINKS RACE AND PREMORTALITY

April. After Joseph Smith’s death Orson Hyde compared those saints who remained undecided between following Brigham Young or Sidney Rigdon to premortal spirits whose indecision assured them birth into black bodies in mortality: “Those spirits in heaven that lent an influence to the devil, thinking he had a little the best right to govern, but did not take a very active part any way, were required to come into the world and take bodies in the accursed lineage of Canaan; and hence the Negro or African race.” (Speech of Elder Orson Hyde, Delivered before the High Priests Quorum of Nauvoo, April 27th, 1845, upon the Course and Conduct of Mr. Sidney Rigdon and upon His Merits to His Claim to the Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 30)

First recorded statement of a Church leader linking pre-mortal indecision with the black race

First recorded statement of a Church leader linking pre-mortal indecision with the black race.

1847

MCCARY ASKS THE TWELVE FOR PROTECTION

March. William McCary, a recent black convert baptized by Orson Hyde meets with the Twelve to ask them for protection from racist saints. Though born a slave in Mississippi McCary’s appearance was such that he sometimes passed as an “Indian.” McCary had an enigmatic but, for some, an attractive personality. He was both a gifted musician and storyteller and often performed for the saints as a source of their entertainment. Many Church members, however, were uneasy and even critical of McCary for marrying a white wife, Lucy Stanton. According to McCary, some would say smugly, as they passed by, “there go the old nigger & his white wife.” McCary asked the Twelve to examine him carefully to see if he were black or Indian. In either case, McCary entreated them, “All I ask is, will you protect me—I’ve come here & given myself out to be your servant.”

Brigham Young responded, “Its nothing to do with the blood for of one blood has God made all flesh.” He then added for emphasis, “We have one of the best Elder an African in Lowell [Massachusetts],” referring to Q. Walker Lewis.

McCary went on to say, “If I am a darky, I want to serve God.” To which Brigham Young said, “Amen.”

A bit later in the conversation McCary said, “I want you to intercede for me. I am not a priest, or a leader of the people, but a common brother—because I am a little shade darker.” To which Brigham Young replied, “We don’t care about the color.” McCary then asked, “Do I hear that from all?” To which all replied “Aye.” (Spelling, capitalization, and punctuation standardized; “Meeting Minutes of the Twelve, March 26, 1847,” in Richard E. Turley Jr., ed., Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, DVD. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 2002, 1:18)

THE MCCARY DEBACLE

April. Within only a few weeks after his meeting with the Twelve, McCary stoked the ire of Church members in Winter Quarters. For one, he taught strange doctrines like that he was literally old Father Adam whose spirit had transmigrated into McCary’s body or that he was Christ himself. In these and other ways he “professed to be some great one, and had converted a good many to his kind of religion. It appeared that he understood slight-of-hand, the black art or that he was a magician or something of the kind, and had fooled the ignorant in that way.” Far worse, however, was when Church members discovered that McCary had begun practicing his own brand of plural marriage with white women, which ultimately led to a mob of Mormon men chasing him out of Winter Quarters. (Nelson Whipple, Autobiography, 71–73, holograph, MS 5348, LDS Church History Library)

On the 25 of April, apostle Parley P. Pratt vented his frustration about the situation and castigated those who “want to follow this black man who has got the blood of Ham in him which lineage was cursed as regards the priesthood” (spelling and capitalization modernized; Parley P. Pratt, sermon transcript, April 25, 1847, found in General Meeting Minutes, Selected Collections, 1:18).

First recorded statement of a Church leader connecting the curse of Ham to a priesthood restriction

First recorded statement of a Church leader connecting the curse of Ham to a priesthood restriction

ORSON HYDE’S REGRET IN BAPTIZING MCCARY

May. On 30 May Orson Hyde, the one who baptized and possibly ordained him, also strongly preached against McCary’s doctrine and criticized those who “would follow a nigger prophet.” Hyde said, “I was wrong in baptizing this nigger, but on consideration see it was necessary in order that he should have opportunity of fulfilling this mission & taking away the tares who were his kindred spirits” (Orson Hyde, sermon transcript found in Meeting Minutes, May 30, 1847 in Selected Collections, 1:18).

WILLIAM APPLEBY ASSESSES ELDER WALKER LEWIS AND WRITES QUESTIONS TO BRIGHAM YOUNG

May. William Appleby visits the Church branch in Lowell, Massachusetts and commented in his journal that “In this Branch there is a Coloured Brother, (an Elder ordained by Elder Wm. Smith while he was a member of the Church, contrary though to the order of the Church or the Law of the Priesthood, as the Descendants of Ham are not entitled to that privilege) by the name of Walker Lewis. He appears to be a meek humble man, and an example for his more whiter brethren to follow” (William Appleby, Journal, May 19, 1847, LDS Church History Library). Notice how Appleby praises Lewis as an example for whites, while simultaneously expressing his belief that William Smith erred in ordaining Lewis an Elder because of his (Appleby’s) wholesale belief in the curse of Ham idea.

June. After his visit to the Lowell branch William Appleby wrote a letter to Brigham Young and inquired about the propriety of both ordaining blacks to the priesthood and interracial marriage (what he calls “amalgamation,” a common term at the time). Appleby wrote, “At this place I found a coloured brother by name of ‘Lewis,’ a barber, an Elder in the Church ordained some years ago by Wm. Smith. This Lewis I was informed has also a son who is married to a white girl. and both members of the Church then. Now dear Br I wish to know if this is the order of God or tolerated in the Church is to ordained Negroes to the Priesthood, and allow amalgamation. If it is I desire to know it, as I have yet got to learn it” (William Appleby, Letter to Brigham Young, June 2, 1847, Brigham Young Office Files, Reel 30).

BRIGHAM YOUNG GRAPPLES WITH INTERRACIAL MARRIAGE AND MIXED RACE CHILDREN

October. After returning to Winter Quarters, Nebraska from his first journey to the Rocky Mountains earlier that summer, Brigham Young met often in council with other Church leaders there on various subjects. William Appleby—author of the June letter (above) which questioned Walker Lewis’s ordination and his son’s interracial marriage—was present at at least one of these councils where he again brought up these issues. The minutes of this council report that Appleby said: “Wm. Smith ordained a black man [an] Elder at Lowell [Massachusets] & [his son] has married a white girl & they have a child”—Enoch Lewis and his white wife Mary Webster had had their first child together earlier that April 1847.

According to the meeting minutes, President Young responded, “If they were far away from the Gentiles they [would] all [have] to be killed—when they mingle it is death to all.” This hyperbolic statement of Brigham Young’s reflects his deep belief that interracial marriage and bearing mixed-race children was a crime against nature and could ultimately lead to humanity’s demise.

Yet it is clear from his next words in the record that he wrestled to also fully include those in mixed-race marriages in the Church. He continued, “If a black man & a white woman come to you & demand baptism, can you deny them?” And then added, “The law is their seed shall not be amalgamated.” That is, they can be allowed into the Church but they should not have children. This was so because, he said, “Mulattoes [are] like mules, they can’t have children.” This statement reflects the widespread belief common in that day that mixed-race children were defective in some key ways.

Historian Edward Long, for example, had written that mulattoes were “of the mule-kind, and not capable of producing” (source). Prominent biologist of the day, Josiah Nott, had also declared confidently that “the mulatto [is] no more [a negro] … than a mule is a horse” (source). Nott also warned in 1843 that because of the infertility of their offspring, intermarriage between blacks and whites would lead to the “probable extermination of the two races” (source).

Brigham’s statement above about mulattoes clearly displays how deeply he had incorporated such erroneous assumptions into his own personal beliefs. Yet, in his next statement in these meeting minutes he said of such mulatto children that “if they will be eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven’s sake they may have a place in the Temple”—showing that at this time Brigham Young’s inclinations were toward racial inclusion in the temple.

Orson Hyde, also in this council meeting, then shared his personal belief that “if girls marry the half breeds [mulattoes] they [are] throwing themselves away & becoming as one of them.” To which Brigham concurred saying, “It is wrong for them to do so.” (Meeting Minutes of Brigham Young and others, Selected Collections, 1:18)

1849

BRIGHAM YOUNG’S FIRST RECORDED ARTICULATION OF A PRIESTHOOD BAN

February. Contextual Preface: On February 13, 1849 in the Salt Lake area home of George B. Wallace, Brigham Young met with Lorenzo Snow, Heber C. Kimball, and others (bot not all of the Twelve) in an official meeting where Thomas Bullock took minutes. According to Bullock’s minutes, the stated purpose of this meeting was to “appoint a committee to lay off the city into wards.” The meeting opened with small talk and then apostle Lorenzo Snow interjected by “present[ing] the case of the African Race,” asking about their “chance of redemption.” It was at this meeting that Brigham Young first gave a justification for withholding priesthood privileges from black Africans.

(Meeting Minutes of the Twelve, February 13, 1849, Selected Collections, 1:18, Thomas Bullock, Clerk)