George Morris

/ Histories / George Morris

Autobiography of George Morris (1816-1849)

Typescript, BYU-S

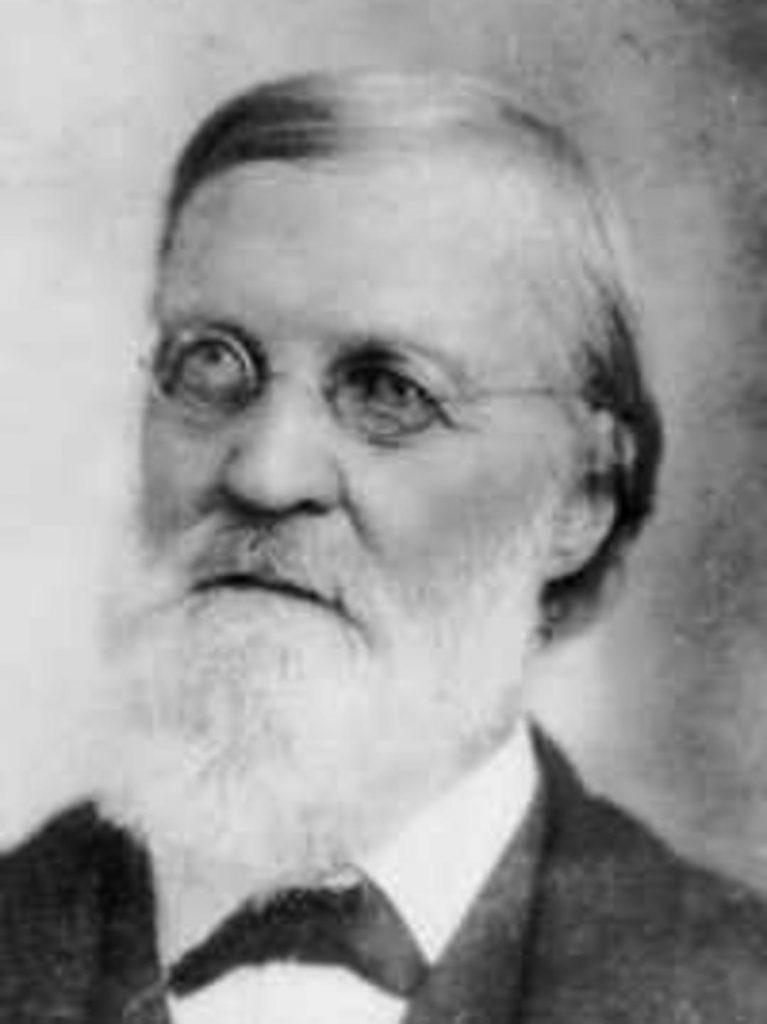

George Morris

George MorrisPhoto Credit: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

I was born at Hanley, Cheshire, England about two miles from the city of Cheshire on the 23rd of August 1816. I was the son of Joseph Morris or Morrey (he was called by both names) and Elizabeth Vernon. My father was the son of James Morris and Hannah Ledsom; my mother was the daughter of George Vernon and Rebecca Goban. My father had two sisters; the oldest was called Nancy and was married to James Dutton and the youngest was called Kitty and was married to Thomas Davenport.

My mother had one brother named John Vernon; he was married, had considerable of a family, and lived in Mancelsfield, Cheshire, England. She had one sister named Mary who was married to Robert Wild and lived at Dukenfield. My father’s sister, Nancy, lived at Beeston and Kitty lived at Perforten. My father lived in Murwardslay at the time of the earliest remembrance. These were all small country villages joining each other in Cheshire, England. My father was a very strict Methodist and a class leader running down deep into error and inconsistency. I have heard him say when describing the torments of the damned that you might take a cat and pluck out one hair every thousand years, and when all the hairs were taken off the cat that their torment had only just begun. He said that we were born in sin and shaped in iniquity, and that there were infants in hell not a span long.

To impress it strongly on my mind that sabbath-breaking was wrong, he said that there was a poor old man once who had nothing to make a fire with, and he went out on Sunday to pick up some sticks. As he was coming back with a bundle upon his back the Lord caught him up into the moon with the sticks on his back to make an example of him that everybody might see. Then he pointed out the figures on the moon to me and said that he had been there more than a thousand years to punish him for breaking the Sabbath and always would be kept there to the end of the world; he said if people would only believe they could be saved, but if not they would be damned forever.

My parents were very poor, and there were six children of us. My mother had had one by a former marriage–his name was James Silverthorn. I was the oldest of my father’s family, four boys and two girls. My brothers’ names were William, Joseph and Matthew. My sisters were Mercy Ann; who was married to Allen Wilkinson and died while crossing the plains to come to Salt Lake and was buried at Deer Creek, aged 32, leaving four children named John, Fanny, Marry Ann and Sarah; and Fanny who died when about eight years old. My father was a foreman shoemaker, and his earnings were very small, in consequence of which he was unable to send me to school.

When I was a small boy, I was very fond of books. I saved every copper that I could get hold of and spent it in buying little books until I had acquired enough to make quite a thick little book and sewed them all together in one and kept one book for many years. I prized it very highly and by that means more than any other learned to read. I would go to school a week or two, occasionally, but there was nearly always something that I could do by which I could earn a few coppers. The commons was covered with low green bushes which produced a blackberry something like a black currant but they grew only one in a place, not like currants. They lasted nearly all through the summer and sold readily in the market, so my mother and her children were kept busy picking them all the season while they lasted. During harvest time we were kept busy gleaning and in the fall digging potatoes for the farmers, so that I was kept so busy nearly all the time that I had no chance to go to school.

When I got to be about seven years of age I was put out among the farmers to work. The first thing they set me to do was to go around the wheat fields to scare the sparrows off the grain, they being very destructive for two or three weeks before harvest. I was armed with a pair of clappers made of three small oak boards. The center one had a handle to it which I had to keep rattling all day long from early morning until sundown hollering and throwing rocks at them all the time for which I got my victuals. Sometimes I was employed herding the cows in the pasture; at other times I drove the horses for the plowmen, two or four in a string, one before the other, by word of mouth and the aid of a long switch of a whip. So particular were the farmers about plowing straight furrows that if the hind horse did not step every time with one foot in the furrow and the other on the land, very likely I would be struck between my shoulders with a great clod and have the breath almost knocked out of me, for the poor boy was always held responsible for every crook that there was in a furrow. I got unmercifully beaten and kicked almost everyday. It was a miracle that they did not beat and kick the life clean out of me.

It would get so muddy turning at the ends and raining so often that my feet would stick in the mud so that I was unable to liberate them, and the horses would come tearing round through it and step onto my foot and go over me to come near killing me very often. As I had to stumble through the clods around from six o’clock in the morning until six in the evening, I would get so tired that I would scarcely be able to get home at night. After passing through this kind of an ordeal for several years, my father thought that it would be better to teach me the shoemaking business; but when I came to be closely confined and having to lean over my stomach all the time, it was harder on me than the bad usage I had been receiving. I had to leave it and go back to the farmers again, and I commenced to hire by the year with them.

I worked for one and another of them until I was about 15 years of age. I then engaged as ostler and waterer at a small country inn and tended a garden and a race horse. An incident occurred while I was living there which I will now relate. I was then in my 15th year and had come to the conclusion to take a decided stand against the tyranny, oppression and abuse which I had to endure so far in my life and to defend myself against all who might attempt to impose upon me in the future be they high or low, rich or poor, Jew or Gentile.

Near the end year an incident occurred which tested me as to whether I had the necessary grit to carry out my determination. It is the custom in that country for the farmers to pay their rent twice a year, and on such occasions a free dinner is given by the landlord at some public house. The steward of the estate attends to receiving the rent, and they generally have what is called a jolly time–that is, they eat and drink all they can. At this particular time, they had nearly all got through with that and gone home, but among the few who were left were a great steward and the village school master. These two very important personages were large, fat, big-bellied men, so it took longer for them to satisfy their stomaches than it did the rest. At about midnight they began to tell about going home, so the steward called for his horse, and I brought him out immediately and placed him to the steps in front where it was very convenient for him to get on. I waited there for some time. Finally he came staggering along to the front door. The school master followed trying to persuade him to go back and take another glass, so after staggering around awhile they concluded to go back and have another talk and another glass.

The night was a cold one, and since they had been standing there a good while and I was feeling pretty cold, I spoke very politely to him and said, Mr. Spencer, shall I put your horse into the stable again until you want him, if you please, for I am very cold?” He made me no answer, but he stepped forward on the platform and struck me a fearful blow between the eyes over the horse’s [back], as I was holding the horse for him to get on, which caused the blood to fly in all directions. He then went off to get another glass as unconcerned as if nothing had happened, but he had raised my dander to a pretty high pitch, and the first thing I did was to let his horse go and give him a kick in the belly to start him off. I then went to the pump and pumped water on my head for half an hour before I could get the blood stopped.

I then went into the house and watched for a good opportunity to pay him back in his own coin. Presently he got up on his feet with his face towards me, and while he was talking to the school master I bounded from my seat like a tiger and planted him a well-directed blow with all my might right between his eyes about the same place as he had struck me. It sent him reeling head long right for an open doorway that led down into a cellar, and he was only prevented from going down by the landlord’s daughter who was standing by the door. Then as I had settled with him I walked out the front door passing by his servant man who was standing in the doorway at the time and had seen his master strike me and had caught the horse when I turned him loose and had also seen me strike his master. I ran for the barn and got up into the hayloft and burrowed down into the hay as deep as I could get. It started a great excitement in the house, and they ran in all directions in pursuit of me. But when they asked his servant which way I had gone, he put them on the wrong track saying I had gone up Stritten lane like lightning when I had gone directly the other way.

After searching in all directions for an hour, the landlord brought a man by the name of Thomas Hedge, who had been assisting me that day, into the barn with a lantern to search the hayloft for me. He sent him up into the loft while he stood down in the barn directing him to pull the hay up and look in this corner and that corner and swearing that he woulll me for disgracing his house if he could find me. He said that Mr. Spencer should kill me like a damned dog for what I had done to him for I was not fit to live another hour. Thomas passed back and forth over me and looked in every other place but where I was. He had seen the affair all through, and he told me afterwards that he could have caught me and held me very easy if he had wanted to, but he said that he wasn’t going to see me abused by the old tyrant anymore. His servant told me afterwards that he could have found me in a minute if he had wanted to, but that his master was a damned old tyrant or he never would have struck a poor boy such a fearful blow in the face as he had done me.

A day or two after the occurrence he came down on purpose to tell me to keep out of the way for he had heard his master say that he was going to send word to Mr. Harrison to secure me and he would come down on a certain day and horse-whip me to within an inch of my life. He said that if he heard anymore about it he would come and let me know, for he did not want me to fall into their hands because they would be sure to kill me like a dog among them.

The next day or morning after it happened I crawled out of the hay in good season and done up my chores in good order. The servant girl called me into breakfast, and while I was eating the old boss came down from his bedroom. He did not take time to put on his shoes before he came to where I was, and in a terrible rage, he cursed and swore until he foamed at the mouth. He made terrible threats about what he would do but was afraid to tackle me, so I sat there with one eye on my breakfast and the other on him until I had eaten what I wanted to. I then got up from the table and stood before him. I said, “Mr. Harrison, if you will, just pay me what you owe me, that will be all that I will ask of you for. I have been treated like a dog long enough.” This enraged him beyond bounds, and I thought sure that he would jump onto me. I had expected it from the first and had made my plans how to defend myself. I would run head against his belly and catch him by the thighs and dump him with his head on the floor hard enough to quiet him down, for he was a low-set, big-bellied, little man as thick as he was long. It would have been just as easy to set him head downwards as any other way.

Several days passed and I heard no more about the horsewhipping. But I kept a close watch on everybody lest someone should attempt to bind me. It would not have been a very easy job for most ordinary men to undertake, for I was about as strong as a small lion. I was low in stature but of well-developed muscle and scarcely knew my strength. Several more days passed and he did not come, when early one morning the servant appeared. He had come to tell me that there was now no danger of me being horsewhipped for he had heard his master talk about the matter to some gentlemen last night. He had said that he had done wrong in striking me, that I had served him right, but he hated it so damned bad to be struck by a little sassy devil of a boy that he had thought of horsewhipping me. He now thought that he should give it up. So the thing blew over without my receiving any further abuse, but it was a long time before he heard the last of it. The gentlemen at their hunting suppers would rig him terribly about it, and the Squire would tell him that if he did not behave himself he would send for Harrison’s boy and he should give him another drubbing, but it made me lots of friends. It spread all r the country and everybody I met would want to know what I had been licking old Tom Spencer for. They would say that it served him right, but they did not know how I durst undertake to do it. They would say that I was a gritty, little devil or I wouldn’t.

After that all the tavern keepers around the country wanted to hire me for the next year and were willing to almost double my wages to what I had been getting. Old Mr. Harrison got mad about it and said he had the first claim on me, and they ought to wait and see whether he wanted me first. Ed, the whiperin, came down the hall to hire me; he said he wanted me in his stables to help him to take care of his hunting horses. He had five in number for his own use (he was a breakneck rider), and he said I was just the kind of a fellow he wanted. He would give me more wages than any of the others, and he would see that nobody abused me there.

Squire Leech kept two packs of hounds one for hunting foxes and the other for hares. They had two hunts a week during the hunting season. Fifty hounds were a pack, and there was a huntsman whose place was at the head to keep the dogs in the scent. The whiperins place was behind the does to keep them together. When one dog got the scent the whole pack kept up the howl and followed the fox across the country through fields of grain, over walls, hedges or ditches or through rivers. All the Nobility, as they were called, wore red coats, white breeches, and top boots. Rich merchants and others could go in the hunt, but they were not allowed to wear red coats.

Well, I had just entered into my 16th year and I had merged suddenly from a poor, friendless, obscure boy to be quite a notable character. A wide opening had been made for me to enter into high life, but being a sober, thoughtful boy and religiously inclined, I thought it would lead me in a direction that I did not want to go; so I declined to hire with any of them for the next year. I had never spent a single sixpence for liquor during the past year, although I had lived at a tavern; while the young man that lived there the previous year had spent all his wages so that he had nothing to draw at the end of the year.

When my year was up and Christmas came, I left that part of the country and tried shoemaking again for the third time; but as had been the case before, the close confinement and sitting did not agree with me. After enduring it as long as I could, I got up, left it, and struck off about 5O miles to a busy little manufacturing town called Duckenfield which is near Ashton and about eight miles from Manchester. There I got work from a rich cotton manufacturer as assistant gardner. I had gained considerable experience at it during the year I lived at the tavern, and I had charge of a fancy show garden while there.

From that I went to a steam boiler manufacturer, but that was more destructive to my health and happiness than anything I had ever done before. It was there that I lost my hearing; through the continual clatter and stunning blows of the big sledge hammers upon the iron plates, I became so deaf that I could hear nothing only as people would holler in my ears. I also met with a sad accident while at the business by getting the thumb of my right hand caught in some machineryich crushed it bone and all as flat as a copper coin. This disabled me from doing anything for three months. The prospect of my ever being able to hear again was very doubtful, so I had to quit that business. Sometime after I had left the business my hearing began to return to me very slowly, but I never more than partially recovered it. So to a certain extent I had become an old man before I was 20 years of age being both deaf and crippled.

I next went to work in the coal mines. Here also I continued to be very unfortunate and came very near losing my life a number of times; at one time I got my ankle split, at another time I got my right knee badly crushed, and at another time I had come down out of the drift where I was working to get a wedge and had no sooner gotten far enough away to escape with my life when down came the roof like a clap of thunder.

But the worst accident that I met with in the mines occurred some time after this. While I was sitting upon a low rock cleaning out the spout of an oil can, a long slip of a rock fell out of the roof of the mine about five feet and a foot square catching me right across my shoulders and doubled my face and feet together and broke in two pieces, one slid over my head and the other down my back tearing the hair off my head and the skin off my back in a fearful manner and to all appearances had crushed the life out of my body. There were several men there who lifted me up and said that my back was broken.

When I began to come to I saw the glimmer of three candles like a flash and then all would be dark again; my sight continued to come and go in this way for some time before I began to realize my condition. Then I began to try to ascertain whether my back was broken or not by drawing up my legs and then stretching them out again. I soon realized that it was not broken and felt very thankful indeed. They put me into a coal wagon and one of the men took me to the shaft. The distance to the shaft was eight hundred yards and the distance from the bottom to the surface was three hundred yards perpendicular. In about two weeks I had so far recovered as to be able to walk about a little, but it has troubled me more or less all through my life. For many years I was hardly able to get through a whole year without being laid up a spell with my back, and I think that by this time that I was about ready to join the ranks of the old men.

I left the coal mine and went to making shoes again (4th) this time on my own hook. I was about 21 years of age and had always been religiously inclined, and a great lover of books. I had kept myself pretty clear from most of the vices to which youth is subject, and had lived a pretty good moral life. I never acquired the habit of drinking liquor, smoke or chewing tobacco nor taking snuff. I spent my leisure time in reading and study; I never learned how to play cards, dice or dominoes; I never engaged in gambling or betting in my life. I had in some degree the charge of my mother’s family for a year or two, she having moved where I was since my father was absent nearly all the time. About this time my mother was taken sick and in about two weeks after, she died. It was in October 1839. She was aged 45 years; she was interned in the burial ground at the Provedence Chapel, Dukenfie1d, Cheshire, England. My father then came to live there and took charge of the familself.

On the 6th of January, 1840, I married Jane Higginbotham, an orphan girl about 19 years of age; she had a baby on January 23rd, 1841, and died April 17, aged 20 years and 3 months. She was interred by the side of my mother. We had been married in Parrish Church at Ashton, Cheshire, England. The baby was a girl and was named Jane after her mother. She died October 9th, 1841, and was interred with her mother. These bereavements caused me to feel sorrowful, to reflect much about religion, to read the scriptures, and to pray for light that I might understand the principles of salvation. I had always been earnestly engaged seeking after the truth; I had made a practice of attending as many of the meetings of the different sects and parties as I could get to, of identifying myself with several of them, and of enjoying myself pretty well for a short time with each of them but I could not rest satisfied long with any of them. I learned in a very short time about all they professed to know about religion and it came far short of satisfying me. I had visited all the sects and parties around the country within reach and had concluded to stand aloof from them all for I considered that they were all lacking the true principles of religion. After that I would frequently meet some of the ministers of the different sects to which I belonged who would claim me as a member of their church saying that they had converted me, to which I would reply that there was where the trouble was; that if the Lord had converted me I should have stayed converted. They would call me a backslider and labor with me to bring me back into the fold again. I told them that I could not feel as they said they felt. I could not enjoy religion as they said they enjoyed it; I could not jump and clap my hands and shout “Glory, Hallelujah, Amen,” as they did; I could not say “He is coming just now,” “We have got Him just now.” I said that it looked to me more like they were crazy than religious. They would then try to scare me with hell fire, damnation, the bottomless pit and ever-enduring torment and then wind up by praying that the Lord would shake me over the pit of hell and show me my awful condition before it was too late. But I had become such a hardened sinner that all their powerful reasoning had no effect at all upon me for I did not think that I was half as bad as they said I was.

I had never allotted myself to get into the habit of swearing or using bad language, stealing or fighting; I never had anything to do with litigation; I was very conscientious in all my dealings and strict in keeping my promises. I will mention a little incident which will verify this fact.

I was coming from the market one Saturday night, and there was an old man on the side of the road selling some books. There was one that I wanted, but I lacked a halfpenny of having enough to pay for it. “Well you can take it,” said the old man. “You are an honest boy; you will pay me sometime.” “Well,” I said, “if you will allow me to take it, I will pay you the halfpenny next Saturday night.” When Saturday night came I walked two miles expressly to take the halfpenny to him, having no other business to call me that way. When I handed it to him he said, “Oh I knew you were an honest boy. I would not be afraid to trust you with a sovereign, and the Lord will bless you all your life.”

About six months before I was married, my half-brother James Silverthorn married my wife’s older sister. They had two children. The younger was called Martha and the older called Elizabeth. Their mother’s name was Mercy, and she was the daughter of Matthew and Nancy Higginbotham. They had two uncles; Matthew and James. About this time my brother Joseph got severely burned in the coal mines by an explosion of fire damp. It was in the year 1840, and he was visionary and flighty in his mind ever after. I had come to the time when I first heard the sound of the everlasting gospel. It was in the month of March, 1841. Some of the Elders had just made their appearance in the small town where I lived and called Dukenfield and Cheshire England. The way it came to me was as follows. I was sitting in my shop making shoes. The door was open, and some little children stopped before the door to play. My attention was arrested by hearing them talking about people they called “dippers.” They said that they dipped people over head in water and talked gibberish in their meetings, and the children tried to imitate speaking in tongues. I asked them where they held their meetings, and they said, in an old room up town and pointed it out to me. So I made them visit the next week.

I heard something at the first meeting that suited me better than anything that I had ever heard from any of the sectarians. I was not very hasty in joining the church; I took time to investigate the principles of the Gospel pretty thoroughly, attended all the meetings that I could get to, borrowed a Book of Mormon from one of the Elders, and commenced reading it very earnestly and prayerfully. I had not read far before the spirit of the Lord bore testimony to me that it was the truth of heaven. I continued reading until I had read it through and got testimony after testimony concerning the truth of the work and divine authenticity of the Book of Mormon and concerning a Prophet, Seer and Revelator having been raised up in those last days with all the power, authority and Priesthood necessary to build up the church of Christ upon the earth. I received testimony that the Elders preached the truth from heaven, that the organization of the church was according to the mind and will of heaven, and concerning the gifts of the Spirit and the gathering.

Before I was baptized I walked eight miles to attend a fast meeting held by the Saints in the carpenters hall in Manchester, fasted, and at four o’clock in the afternoon they had what they called a tea party. But there was no tea there; they had hot water with plenty of good cream and sugar and plenty of something good to eat. I partook with them as though I had been one of them, and felt in my heart that it was the richest feast in my life, and the best company that I had ever enjoyed. The gift of tongues, the interpretation of tongues, and the spirit of prophesy was poured out richly upon the Saints and they sang the sweet songs of Zion. Such a heavenly influence rested down upon the assembly that it was in very deed a rich foretaste of heaven.

For about a week before I was baptized I took a way one Sunday afternoon up by a beautiful riverside into a retired place for the purpose of meditation and reflecting undisturbed upon than of salvation which had occupied my mind very forcibly for some time. I prayed to my Heavenly Father in secret and confessed my sins. I had one of the most refreshing seasons that I ever experienced in my life, for my soul was truly humble before the Lord. My sins were made manifest to my mind; my ignorance and my imperfections were shown to me, and I felt my weakness so keenly that I wept again and again over my condition. As I lay prostrate on the ground I poured out my soul in prayer before my Heavenly Father in the name of Jesus Christ confessing my sins and asking forgiveness from the Lord. I covenanted with the Lord that I would forsake all my sins and begin from that very hour to lead a new life and serve him the remainder of my life to the best of my abilities if I could but obtain his Holy Spirit to assist me for I felt that I could not do it in my own strength. He heard my prayers and poured out his Holy Spirit upon me mightily which caused me to weep for joy and rejoice that the Lord had been so merciful and good unto me all through my checkered life. My heart was made as light as a feather that very hour for a change had taken place which caused me to feel like I was in a new world; the rippling in the river was like sweet music in my ear, and the birds sang sweeter than I had ever heard them before. I looked forward with joy to the time when I should be baptized and enter in through the door into the kingdom of God, for I had seen it and had a foretaste of its joys, which to me were sweeter than honey from the honeycomb.

I have now nearly got through with the history of my early life; I will mention one or two more little incidents before I commence with my baptism. There was a firmness and decision of character accompanied me through my youthful days that was really exhibited by the young men of my acquaintance. When I lived at that tavern during my 15th year I never spent as much of my wages as would buy one pint of ale while the other young men spent all their wages in drink. Another circumstance was that when I worked with the boiler makers and coal miners, they had a custom of paying us our wages on a Saturday night at some public house where they had to spend some for the good of the house. I would pay my share of the money but would not drink. Then I would leave saying that I had some important business to attend to [for I could not endure their obscene language and ribald songs, their cursing, tobacco fumes–I could not endure it.] When I could avoid it, of course, they would curse and abuse me and tell me that I thought myself too good for their company; but that did not make me like them any better.

There was one more thing which happened when I was a very small boy which I feel very delicate about mentioning. My father was an inveterate smoker according to his means and circumstances; he was out of tobacco and there was no bread in the house for the children’s breakfast nor flour to make any and but one penny to buy anything with. A controversy arose between my mother and him whether the penny should go to buy tobacco or bread; but, of course, father being the strongest party, it had to go for tobacco. It seemed as though my mother’s heart would break with grief, and it made such an impression upon my little mind that I vowed that I would never use tobacco while I lived. I have kept my vow inviolate to this day.

Now e got through with my history up to the time of my baptism. At the time I had that joyful season in that retired place on the riverside, I made up my mind to be baptized the following Sabbath morning. The week that intervened seemed like an age almost; I felt so much afraid lest something might intervene to prevent it. But when Sunday morning arrived I arose at a very early hour, it was about four o’clock and called upon the Elder that I had selected to baptize me. We resorted to the place where I had spent the previous Sunday afternoon, and he baptized me. His name was John Albiston, Jr. In my ignorance and simplicity I requested him to baptize me a second time, considering that once was hardly sufficient in my case, but the Elder said that it was all sufficient and to do anything more would be doing beyond the order of heaven and would not be acceptable.

So I was satisfied, and oh! it was a season of joy and rejoicing such as seldom falls to the lot of poor fallen humanity while traveling through this wilderness of sin and sorrow. It was about the dawn of day on a beautiful midsummers morning; the scenery was enchanting, the birds had commenced to sing their sweetest morning songs and all creation seemed to rejoice with me for it was a very important crisis in my life crippled as it was with the circumstances of the greatest moment to me. It was the time when I was born a child of God and entered in through the door into His Kingdom and put off the old man with all his deeds. I put on the new man, Jesus Christ, and it was the time when I stepped forward to become the pioneer of my father’s family for I was the first one to receive the principles of the gospel. The date of my baptism was June 28, 1841 in the suburbs of Staily Bridge, Lankanshire, England.

On the 5th of September, 1841, I was ordained to the Aaronic priesthood and preached the gospel some little in the small branches around. I baptized six persons, but the principles of the gathering had begun to be preached, and I caught the spirit of it. From that time forth I never parted with a sixpence necessarily until I had accumulated sufficient means to emigrate to Nauvoo.

On the 1st of February 1842, I started from Bukenfield on my way for Liverpool, and one of my brothers named William and my sister Mary Ann accompanied me on my way until we came to a river and went down to the water. I baptized them, and they returned home. I went on my way rejoicing. [page 19 missing] place as I had described and returned quite disappointed and told me that I had deceived her and she was quite vexed at me and I asked her if she thought that I was that kind of a man to lie to her like that and I told her that she had not found the right place and described it to her again and the next day she actually fixed herself up again and went in search of it a second time but returned with the same results. Then they suspected that my mind was out of balance and her husband and her quizzed me so close that they detected me and strange as it may appear they had never mistrusted me before, in all the strange stories that I had been telling them. And thus it was that the struggle between life and death had been going on within me and death had well nigh gained the victory and the lady had called in some of neighboring sisters to come and stay with her one night to see me die. And they were talking about me and expressing regret that a young man like me should be taken away in the prime of life not thinking that I could hear anything they said when a gleam of consciousness came over me and I spoke to them and said that they must not talk about me dying for I was not going to die.

That same night when Sister Smith was fixing me as comfortable as she could in bed and tucking the clothes around me, I said to her, “Sister Smith, cover up Jane,” and she said, “What do you mean George?” and then turning towards the other sisters she said, “He is rambling in his head, he is thinking of his dead wife, he is nearly gone. He cannot live till morning.” I spoke to her again and said, “Cover Jane up same as you have me. She is lying in bed on the other side of me there.” She said, “There is nobody but you in bed, you feel very sick don’t you, do you want anything else?” Then she left me, I was just about to pop through the veil and the spirit of my dead wife was hovering over me, I saw her explain as I ever did in my life and talked to her and said, “Jane, how is it that you are permitted to visit me?” And she said, “Because you have been baptized for me in the temple.” On the 23rd of August 1843 I married my second wife at Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois. She was the daughter of James Newberry and Mary Smith. She was aged twenty years, four months, and 10 days and I was 26 years old on the day we were married.

In the fall of 1843 I had a very narrow escape from being drowned in the Mississippi River. I had been up to Burlington Island and with three others went to get a raft of firewood and we were trying to land it at Nauvoo. We had swung the hind end as near to shore as we could get it and thinking that the water was shallow I jumped in to carry a rope to shore but in place of being shallow it proved to be over ten feet deep where I jumped in and a perpendicular rock there and being a very windy day the waves dashed on the shore and then fell back again with a great force driving me further into the water, after struggling for my life for a short time to get to shore found I could not make it and having let go of the rope in the struggle I turned and made for the raft again thinking that by the aid of the waves I might be able to gain it but having on a heavy blanket coat and big boots they soon leaded with water. And not knowing how to swim I went down like a lump of lead striking upon the bottom on my feet and not having lost my presence of mind I had closed my mouth and kept water out of me and remembered the rope.

It was a heavy cable about fifty feet long and I remembered the direction the raft was in when I went down, so I raised my hands up and groped for the rope stepping one way and then the other on the bottom of the river in the direction that I thought the rope would be in and miraculously as it may appear, I caught the rope when it was within two feet of the end and commenced hauling it in hand over hand until I began to think that there was something wrong, it seemed too long, when I popped up with great force about four feet behind the logs, if I had struck them with my head it would surely have killed me. I crawled out onto the raft and stretched myself out perfectly exhausted and the raft floated down the river a mile before we landed it. Now, how I came to catch that rope in my hand and how I was able to hold my breath as long as I did I cannot account for unless my guardian angel who has chover me was there to direct me in such a manner.

In the summer of 1844 I made brick in William Law’s brickyard while engaged at work on the 28th of June word came into the yard that Joseph and Hyrum had been murdered the day before in Carthage jail by a mob and their dead bodies would be brought into the city that afternoon. A procession was formed on Malluland Street to receive them and escort them through the city to the Mansion House, Joseph’s residence. Many thousands of people assembled and such a time of mourning I never witnessed, neither before nor since. Some express their sorrow by weeping and some by praying for vengeance on their murderers and some could neither shed tears nor speak and a good many wanted to go and take vengeance on their enemies and murderers by laying Carthage in ashes but through the influence of Parley P. Pratt, Willard Richards and other influential brethren the people were calmed down and the corpses were taken to the Mansion House to be prepared for the Saints and friends to take a last sad view of these they loved so well. On the 29th, not less than ten thousand people assembled at the Mansion House to view the remains of the martyred Prophet and Patriarch for the last time and a heart rendering scene it was, I was one among the crowd who went to see him.

My first daughter Lavine by name was born about one month after Joseph was killed. In the winter of 1844, I had another narrow escape from being drowned in the same river. I had been over into Toway digging a well and had finished it about noon and started to come home and when we got to the river it was dark. The river was frozen over so as to bear teams up hauling wood and they had made a track on the ice but the sun had been pretty warm that day and had melted some snow so that the water had flowed over the track and obscured it so that it was not plain and there being no moon we lost our way while crossing and having no object to steer by we had to guess at it and the man that was with me was pretty badly scared. I had to go before him some distance before he would venture to follow me, so I came to a place where the ice was tender and not knowing what way to take to get off of it I thought it would be the best way to step lightly and go quick so I stepped off in a light springy gait and had not gone more than a rod when I plunged head long into an airhole, one of those places that remain open in all large rivers and do not freeze in the winter. The place was about a rod wide and a rod and half long down stream.

I had a long barrelled shot gun in my right hand at the time which I held onto. I was always remarkable for presence of mind in danger so I closed my mouth and kept the water out of me and although I had no knowledge of swimming as natural instinct led me I soon found myself in the best position possible for catching on the ice when the current carried me down to it. I was floating as near the surface of the water as the weight of the shot gun held up out of the water in my right hand would permit me. When I struck on the ice with the gun butt it broke, in an instant I struck again and it broke but the fourth time it didn’t break and I was enabled to raise my head out of the water and take in a breath and rest for a moment. I then raised my left hand and examined the thickness of the ice, the thin edge had broken off until it was nearly two inches thick but that was not sufficient for me to attempt to get out, so I placed the gun as far over on the ice as I could and raised my other arm out and g upon the edge of the ice by my arm holes, the current ripping by me and pinning me up against the under surface of the ice as close as it was possible for me to be.

I then looked around for the man that was with me and saw him standing about four rods distant from me struck perfectly motionless like a statue. I called to him, he was my brother-in-law, and he said, “George, are you there?”

“Yes,” I said, “There is hope yet; go down about three rods below me,” for I could see then where the ice was strong as my face lay flat on the ice and, “run to the shore as fast as you possibly can and see if you can find a rail or a long pole and hurry back with it and I will try to hang on till you come back,” so he flew off like a cloud and was gone what I thought to be about twenty minutes, whether that was correct or not I cannot say but it seemed to be an awful long time. Presently I heard his voice calling to me and I answered it and he kept calling and I answering until he got to me with a long round pole on his shoulder and he said, “I’ve got a pole; where will thou have it George?” so I directed him to go two or three rods below me and lay the pole toward me bearing his weight on it about six feet from the end until I could reach it in the same position, he done so and I reached over and placed my hands upon it and with a superhuman spring which any human being could not make without divine aid I landed right out of the water upon the weak ice, as light as a feather and I pushed and he pulled bearing our weight upon the pole as much as we could until we got on the safe ice, for we had to go some distance before we reached it, our weight causing the weak ice to sway so that the water flowed over it several inches deep.

O, dear it makes me hold my breath while I am writing it but we got on to safe ice and made our way off it as soon as we could. Now if there was anything in the other case that made a great miracle of it, there is not in this one.

I had over two miles to walk before I got home and a bitter cold frosty night it was and the pain, a torture that I endured from the cold cannot be described, my clothes froze stiff upon my body and every step I took had to break the ice to do it; crack, crack was the sound I made every step and it seemed that every joint of my body was being torn but by main force. My shoulders wanted to drop out of their sockets and I had to hold on the collar of my coat to prevent my arms from falling out. My body seemed to be entirely separated into two parts at my loins and it was with the greatest difficulty imaginable that I could make any use of my legs but by the assistance of my brother-in-law I succeeded in getting home, after a tremendous struggle. My wife made up a good hot fire and plenty of good hot pepper tea and I went off to bed and she piled all the clothing there was in the house onto me and I fell asleep and thawed out and my joints got back into their places and the pain left me.

When I woke up I was not much worse for wear. Now, how anything more marvelous could happen to a human being and yet he be able to survive it, I am at a loss to imagine, I have never heard nor read of a parallel case to it in all my life. I forgot to mention one point in its proper place: when I sent my brother-in-law in seh of a pole, the pole he brought lay ready for him to pick up, the first thing that he saw when he set foot on the land. I have not desire to take any credit to myself for my own smartness in extracting myself from those difficulties but feel to give God the glory and the honor of my salvation and acknowledge his hand in all things, Amen.

One would think that when our enemies had succeeded in taking the lives of the prophet and patriarch that they would have been satisfied for a time at least, but no they continued to clamor for blood and we were harrassed continually and threatened with having our homes laid in ashes and the rest of our leaders slain, hence we were under the necessity of keeping strong guards on duty day and night. Those were times to try men’s souls. I have been on guard night after night with my brethren on the prairies between Nauvoo and Carthage to prevent the mob from coming in unaware and setting fire to the city and murdering more of our friends. I have lain in the [Nauvoo] temple night after night upon the hard wooden benches with my rifle by my side expecting an attack every minute, I have laid in my bed with my clothes on and my gun leaning against my pillow where I could lay my hand upon it at any hour of the night and jumped from my bed at all hours of the night at the sound of the big drum and the ringing of the temple bell which was a signal for us to gather; and I have been armed and equipped and at the place of rendezvous inside of five minutes. I can say further that I believe that I have lived as poor and worked as hard at the same time as any other man and can say from experience at that time that the thoughts of the thing was always worse than the thing itself, and I suppose it is the case with death, for a dying person never weeps.

About a month after Joseph’s death Sidney Rigdon set up his claim as guardian of the Church, saying that [the church] was not of age to do business for itself being only about fourteen years old and as he was next in authority to Joseph, it was his duty to act as guardian until the church was twenty-one.

On the 5th of August of 1844 a special meeting was appointed for the church to come together to hear what he had to say on the subject. He did not occupy the stand where Brigham and some of the rest of the Twelve were but he stood in a wagon with some of his supporters in another part of the congregation, and occupied the time in the forenoon and ordinarily was very eloquent and pleasing speaker but at that time he made a very feeble effort. In the afternoon President Young replied to what had been said and when he arose to speak I was sitting holding down my head reflecting upon what had been said by Rigdon when I was startled by hearing Joseph’s voice. He had a way of clearing his throat before he began to speak by a peculiar effort of his own, like Ah Hem, but it had a different sound from him to anyone else. I raised my head suddenly and the first thing I saw was Joseph as plain as I ever saw him in my life. He was dressed in light linen suit with a light leghorn hat such as he used to wear in the warm weather and the first words he said were, “Right here in [is] the authority to lead this church,” at the same time striking his hand on his bosom and went on to utter several sentences in Joseph’s voice as clear and distinct as I ever heard Joseph speak and his gestures and appearance were perfect. This was testimony sufficient for me where the authority rested.

On the 8th of October, 1844 at the reorganization of the seventies was organized in the 12th Quorum, Hyrum Daytin Sr., President.

In the month of October 1844, I put me up a nice little brick house, 16 by 22 feet on a lot that I owned, about a quarter of a mile northeast of the [Nauvoo] temple. I had also another lot situated upon Young Street, about one mile east of the [Nauvoo] temple.

The mob continued organizing and gathering apostates into their ranks and threatening to exterminate the Mormons and on the 10th of September, 1845, they set fire to Morley’s settlement and Green Plain, burned all the houses, barns and shops in the settlements and drove the sheriff of Hancock County from his home and tried to kill him, when Porter Rockwell, in defending him, killed a man by the name of Worrell who was a leader in the mob and took active part in killing the Prophet and Patriarch. The persecution continued to rage and people left the small settlements and went to Nauvoo for protection and business was paralyzed. We were kept on guard nearly all the time and many poor men were entirely destitute of anything to eat at times. I was among that number when inquiry was made overnight who was in that condition and next morning there would be several fat cattle to butcher and deal out. The early part of the summer of I engaged to dig a well for Father Bent on his farm, a short distance north east of the city, and while I was engaged in doing it he sold the farm to a mobocrat by the name of Flinn.

Arrangements were made that I should go on and finish it and Flinn was to pay me for doing all the work, so I continued on and when I had gone down about 40 feet I struck water and came out to speak to the man about it, who was plowing in the field a short distance off. I asked him for some of the pay when he got mad and began to curse and swear. There was a pronged root of a young tree which he had plowed up lying on the ground nearby so he ran and grabbed it by a prong and made for me with it. I dodged out of his way, when he sent it whizzing at my head. I ducked down and it missed me; then he put his fingers into his mouth and whistled three times. Then three or four men came running across the field towards us so I thought it best to be getting away from there. I took to my heels in good earnest and ran down by the well and took my brother-in-law who was helping me and we made for the woods which were not far off. We got into the thick brush and thought ourselves pretty fortunate to get away with our lives after having dug the well for nothing.

Later in the summer the mob took Phineas Young, and his son Brigham, prisoners while returning from the McQueen’s Mill with a load of flour passing through the town of Peatusac. They appropriated the team and flour to themselves and dragged them back and forth through the woods from county to county so that their friends could not find them. So, William Anderson, who was afterwards killed, together with his son Augustus in the Nauvoo battle, was appointed a deputy sheriff to raise a posse of 50 men to go in search of them. I was one of the number; we traveled through the night and got into Pontusac about daybreak in the morning. He was almost scared to death and gave us all the information that he was in possession of. He said that there was a large cany of men in the brush just out of town. They were well armed and intended to have a fight, so we scoured the brush on both sides of the road and presently came upon them. Many of them had their rifles cocked and were in the act of taking aim, they were led by the notorious Frank and Chauncey Higbee who had taken such an active part in bringing about the murder of Joseph and Hyrum.

The guard said that the mob numbered three hundred men, so when we came near enough to them to be heard, Captain Anderson called his men around him and spoke to the mob in a loud voice and said, “O, yes we know you are there, and we know how many you number. If there were five times as many there we should not be afraid of you. There are only 50 of us here but there are five hundred a little way back. We have the authority and hold the powers to search the town for our brethren. If any one of you snaps a cap we will lay your town in ashes. We command you in the name of Sheriff Backenstos whose servants we are, to come out of the bushes and lay down your arms,” so they came out but were unwilling to give up their arms. Captain Anderson said to his men, “Now my men each of you disarm his man.”

It fell to my lot to disarm the notorious Chauncey Higbee. He was unwilling to give up his rifle, so I caught hold of his hands as though his arms were no more than straws. We disarmed all of them and took seven of the leading men prisoners; two were the Higbee’s (they were sons of Elias Higbee who was one of the [Nauvoo] temple committee) we searched the town of our brethren but could not find them.

We then started on our way back, taking those prisoners with us. We left word in the town that if anything happened to our friends they need not expect to see the faces of their friends again alive. In three or four days after that our brethren were set at liberty and came home. Whether the team and flour were ever returned I cannot say but I think not. A short time after that occurrence five of us were going up the Mississippi to get a raft of firewood from Burlington Island and when passing through the town of Oquake; we were rowing the skiff up the river and three were walking on shore. One of us called into a store on the river side to buy some matches. There were three or four mobocrats sitting in the store, at the time, one of them said to us, “You are some of them damned Mormons ain’t you? We will make it hot for you when you go down again on your raft.”

When we were leaving the store and going down the bank to the river one of them stepped into the door and fired a shot after us, which mowed the brush down close to our right hands as we were going down a narrow path, one after the other close together. When we went down again we kept pretty well over the other side of the river and went down in the night.

In September 1845 the authorities of the Church made a proposition to the mob that if they would cease their persecutions and assist the people in disposing of their property they would leave the state of Illinois the following spring. In October a delegation of leading men were sent in from Carthage to confer with the authorities of the Church about the Mormons leaving. It was agreed to that the mob should cease to molest us and assist us in disposing ofproperty.

On the 5th of October the first meeting was held in the [nauvoo] temple and it was crowded very full and the floor settled and caused quite a panic and several broke the glass and jumped out at the windows. It was expected that the floor would settle a little but people were not apprised of it. October 6th, General Conference was held in the [Nauvoo] temple, there had been none for three years. William Smith, the Prophet’s brother, was cut off from the church. He had made great threats that he would expose the Twelve and their awful doings and said that there was nobody that durst undertake to cut him off the church. He was a boastful, bullying individual. Then President Young stepped forward to present his case before the people; he said that William Smith had made a great many threats about what he would do, but if he undertook to treat them as he had his brother Joseph, he would find out that he had got the wrong man to deal with for once. He further said that he carried a little toothpick around with him for his own protection, at the same time drawing a long, thin dagger out of a walking cane and presenting it before the congregation, and said it would not be healthy for any man to lay violent hands on him–if they did he would run that through them, so help him God, if he had power.

I will now say a few words about how the mob carried out their part of the treaty in helping us to dispose of our property. O my soul, what trash they brought along to offer to us for our comfortable homes, good brick homes and excellent farms. It seemed as though they had scoured the country for hundreds of miles around for all the old balky, swaybacked, hipshot, blind eyed, ringbones, and spavined things which they called horses. All the worthless breechy, halt, lame and blind old oxen and all broken horned, three-legged, one-footed kicking old cows that could suit themselves into the bargain. Wagons they would bring along composed of an old wheel poked up here and another there, one of one size, and another of another size with broken clinch pins. Axle trees pinned together with wooden pins and wooden clinch pins to hold on the wheels. Old shot guns and rifles with neither lock, stock nor barrel. I mean things that were perfectly useless, which from their standpoint, considered suitable equipment for us to travel in the wilderness with. Therefore they thought that we would be very eager to trade away our homes to them for such things.

This may be thought by some to be an exaggeration, but I will try to describe an outfit that was offered to me. Two men owned it in partnership; they said they wanted to buy city property with it. They represented it as being a very good team. The near horse was the worst looking thing that I ever saw in my life. His back was curved downwards nearly to a half circle. It was blind in one eye and both knees were lame. The other one had one stiff hind leg with the hip running up to a sharp point way above the other, with some kind of white looking eyes. I could not tell whether he could see at all or not and both so poor they could hardly walk.

The wagon was composed of four old wheels of different sizes. One axle had been broken off about one-third of its length. One end had been made for it with an axe and pinned on with wooden pins. Wooden clinch pins to hold on two of the wheels, an old scooner had been placed upon them. Id scarcely see over the top when I got in to see them move around. They did not believe in moving much. They went along a few rods one way but when they undertook to turn them around to go back, they turned about half around and that was as far as they would go. No amount of persuading could get them to go any further. I concluded that they would hardly suit me and got out and left them. Now, strange and incredulous as it may seem that is as true a picture as could have been drawn of that outfit.

As will readily be perceived we were not much benefited by the treaty that the mob made with us. There had to be something else done to help fit us out for traveling through the wilderness to the promised land. There was a general cooperative wagon shop established and almost everybody turned into wagon makers. The way the wagons were made through the winter of 1845 and 1846 was as follows.

Some went to the woods to cut the timber, others hauled it to the temporary shop, which was erected of boards with boiler furnaces and ovens to season the timber. Some were engaged in splitting and sawing the timber. Others were testing and boiling the brine and other processes to destroy the sap out of the green timber. Others were engaged in hewing, shaving and dressing the timbers. All those who could handle tools were set to mortising, fitting up and putting wagons together. In many instances wagons were set up in from three to four weeks from the time the timber was growing in the woods. A great many wagons were build in this manner, and they done good service in crossing the plains. I have forgotten the number, but they ran up into the hundreds. I had one and crossed the plains with it, and used it several years after I got into the valley.

The fury of the mob continued unabated. They continued to persecute the Saints, one man was killed at Green Plains and another one was poisoned in Carthage. The people living in small settlements around Nauvoo who belonged to the church flocked into the city for protection. One hundred and thirty wagons with teams were sent to bring in the burned out families and what grain they could get from Green Plains. President Young had to hide away a good deal to escape being arrested by the mob officials.

I was working on the [Nauvoo] temple at the time they arrested William Miller and thought they had got him. They were both in the upper rooms of the [Nauvoo] temple at the time when an officer appeared at the door with papers to serve on Brigham Young, with authority to arrest him and take him to Carthage. Someone told President Young they had put two officers at the door waiting to arrest him. When he spoke to Brother Miller he said, “Brother William, put on my cloak and go down to the door and see what they want.” Brother Miller done so and when the door was opened they arrested him and took him to Carthage feeling sure that they had got President Young.

They never found out their mistake until they had reached Carthage and took him into a tavern. The news began to spread that they had got Brigham Young, and they kept him in a room to show him to the mobbers who would keep flocking into look at him, when an old man who was acquainted with him went in to take a look at him and said, “Gentlemen, if you thinat he is Brigham Young you are most damnably mistaken. I know Brigham Young too well to be fooled in any such way as that.” They then asked him what his name was; he said, “My name is William Miller, you might have found that out sooner if you had been smart.” Of course while this was going on President Young was looking after his part of the business pretty sharply. The officers were badly sold and poor William was left to take care of himself.

It was in December 1845 when this occurred. I continued to work steadily on the [Nauvoo] temple for the last six or seven months before the work ceased on it altogether. The last work I done was Peter [Ofine] and myself laid the flight of stone steps in the front of the [Nauvoo] temple.

An incident has just occurred to my mind which had a little fun in it. I think it was in the latter part of July, a special meeting of the Brethren was called, a political meeting of some kind I think, with reference perhaps to making an appeal to the President of the United States and the Governors of several states in regard to our present condition and treatment which we had received from the states of Missouri and Illinois. It was held in a hollow a little southeast of the temple; a very bad person, a doctor somebody, I have forgotten, Dr. Charles (John F.) was there in attendance for the purpose of taking notes and observations to bring nore trouble upon us if possible. When the meeting was dismissed, a company of young fellows gathered around him, with a stick in one hand and a knife in the other and struck up a lively tune by whistling, beating time by whittling the sticks and slashing out the knives as near to him as they could without touching him.

If there was ever a more thoroughly scared man I saw one there. He looked on every side with a terrible anxious and uneasy look for a chance to break away. They were so very close around him and had such awful looking knives, everything from a common jack knife up through all the different grades of butcher knives to the largest kind of a carving knife, so he was obliged to wait until they got through with him. I did not join the crowd, but I enoyed the fun as much as any of them. When he got away he went and made complaints to President Young and other authorities and said it was perfectly outrageous that a gentlemen and a stranger should be treated in such manner as that in a free country. The president said in reply that he supposed that the boys considered themselves to be living in a free country. And that there was no law that he knew of againist whistling or whittling. That he sympathized with him very much in his troubles, his cause was just but he could do nothing for him. This was meant as an offset to the reply that President Polk made when appealed to by the Saints in Missouri trouble. President Young could enjoy a good joke as well as any man and so could the rest of the Brethren.

On June 3, 1845 the Legislature of Illinois repealed the city charter of Nauvoo and at the conference its name was changed to the City of Joseph. Another item occured to my mind which I should before I the forepart of the same month in which Joseph was murdered. The first number of a paper called the Nauvooo Expositer was published. A paper of the Salt Lake Tribune stated, Joseph said that Nauvoo was not large enough to hold him and that office at the same time; that he would rather die tave that paper go on. He being mayor of the city called the City Council together to deliberate on the paper and they unanimously declared it a nuisance and passed an ordinance to abate it. Three days later the City Marshall with the police broke up the press and threw it out and scattered the type all over the ground about the office. That caused a great commotion in camp and all hell was stirred up and Warsaw Signal, or Stinkall more properly speaking, howled and the apostates and mobocrats joined their forces together and said that if that could not reach him, powder and ball should.

So on the 27th of the same month the secret combination was permitted to carry out the hellish purpose. The Warsaw Stinkall seemed to be the paper to give the signal when to strike the fatal blow, that sealed the doom of the state of Illinois. It seems also that wherever the headquarters of the Kingdom of God is established over the earth, there the head of Beelzebub is established also, for that paper was a true representative of the dark legions of Sheol and its editor was a true representative of his father Balial. So it is today with the Salt Lake Tribune and its whiskey scribblers.

The last three years of the history of the Church in Nauvoo, namely 1844 was the crowning point of the power of the apostasy and mobocracy and the shedding of innocent blood, they murdered Joseph and Hyrum, William Anderson and his son Augustus, and a number of others. Joseph’s two counselors, Sidney Rigdon, and William Lab apostatized, three of the Twelve; William Smith, John E. Page and Lyman Wight. John C. Bennett, mayor of the city and Mayor General of the Nauvoo Legion; also William Marks, President of the Nauvoo stake of the Church. Alpheus Cutler, one of the [Nauvoo] temple committee, Francis Higbee and Chauncey S. Higbee, sons of Elias Higbee. Wilson Law, Dr. Robert Foster and brother Charles, all leading men and men of influence apostatized and a great many others who only hung on by a very slender thread fell off afterwards. James J. Strange set himself up as a Prophet, Seer and Revelator to lead the church to the Devil if they would follow him.

It seemed to be a pretty hard struggle at that time for the church to keep life in it. So the woman had to flee into the wilderness with the manchild where a place was prepared for her where she could be nourished for a time, times, and half a time and there was given her two wings of a great eagle, that she might get out of the dragon. The serpent cast out of his mouth water as a flood. After the women that he might cause her to be carried away by the flood which the dragon cast out of his mouth. The dragon was wroth with the woman and went to make war with the remnant of her seed which kept the commandments of God and had the testimony of Jesus Christ. This is what John the Revelator said about it 2800 years ago. Who can say that it does not apply unto us in our life.

Certainly the church had to flee into the wilderness and take the priesthood with her and the earth helped her to escape from the dragon of apostasy and mobocracy to a place of safety by placing a distance of over a thousand miles between us and our enemies. This also fulfilled a prophesy uttered by Joseph Smith about three months before he was killed. That is five years the Saints would be out of the power of their old enemies. Whether apostle of the world, John, specifthe time that the woman should be nourished in the place that was prepared for her before the dragon should make war on the remnant of her seed, I do not know. There were some Saints who did keep the commandments of God and had the testimony of Jesus Christ. I do know that we had good peace for over 33 years before the Edmond’s Law was passed.

I will now go back and relate an incident that came under my observation on the evening of 18th of June, nine days before Joseph was killed. The Legion had been called out to parade and Marshall Law had been proclaimed by the mayor; Joseph had addressed the Legion that day. This was the last public address that he ever gave. After they were dismissed they seemed inclined to linger and gather in groups to discuss about the signs of the times and the doings of the mob. There were probably about 50 of us in the group. I was standing on the outside and looking westward when I saw a man on horseback cantering along on the banks of the river going north about 3/4 of a mile from where we stood. I called the attention of some of the brethren to him, saying, “That looks like Joseph, and it is very much like the gait of his horse that he calls Joe Dunkin. Can it be possible that he is riding out alone at this late hour when his enemies all around are thirsting for his blood?”

About that time he halted, being about due west of us, and turned his horses head towards us and cantered right up to us. When within about two rods of us he reigned up his horse, and stood back in the stirrups and in the most cheerful manner spoke to us and said, “Good evening my boys, I call you my boys because you are my boys in the gospel. The wolves are on my track and I don’t know that they will hunt me down this time. They have got another writ out for me and they want to drag me to Carthage. Will you let me go?” We all in one voice cried, “No.” He then repeated again, “Will you let your General go?” Then all in one voice rang out still louder, “No.” He then said, “I knew you would not, God bless you my boys. Good night.”

Then he reigned up his horse and stood in his stir-ups again for a minute or so and the horse danced and capered in beautiful style as though he was very proud of his noble rider. He then turned and cantered away towards home. While the horse was dancing and capering I was looking very earnestly into Joseph’s face and I beheld a halo of glory surrounding his countenance like the dazzling rays of the sun. Whether anyone else saw this or not I cannot say. I have never seen anything about it in print or ever heard anyone speak of it since. He made some very important remarks that day while addressing the Legion, but my memory has failed to retain many of them. A few of his sentiments however, I have retained.

At one time he straightened himself up in a very erect and bold position and drew his sword out of its scabbard and presenting it before him said, “The sword is unsheathed and shall never return to its sheath again until all those who reject the truth and fight against the kingdom of God are swept from the face of the earth by sword, famine and by pestilence and the judgments of the almighty–which he will pour out from time to time until the earth is cleansed from wickedness and made fit to be inherited by the Saints later.”

Joseph having been warned of the Lord to flee to the west to save his life, him and his brother Hyrum and Willard Richards and his trusted servant Porter Rockwell crossed the Mississippi River late in the evening, but his wife Emma and others threw themselves into war of his making his escape by sending a couple of faint-hearted individuals to upbraid him of being like a shepherd fleeing from his sheep in the hour of danger. Joseph could not stand to be upbraided of cowardice and turned around to them saying, “Do you want blood; if you do you shall have it. If my life is of no value to you it is not of much value to me,” turned and went back with them the next day. Thus like his Royal Master before him, had willingly laid by his life for his sheep. President Young, while making some remarks about it on [one] occasion in the old Tabernacle in Salt Lake City said that, “It was Glory and Honor to him but misery to her and to them who were the means of bringing it about.”

I have heard it asserted that on one occasion Joseph remarked to some of the brethren that he expected to ride that favorite horse of his, that he set so much store of, in eternity. That would be pretty strong doctrine for the sectarian world.

In February 1846 while I was working on the [Nauvoo] temple, myself and wife received our first endowments. About this time my wife’s sister Harriet, who was several years younger than her, came to me privately and asked if I was willing to take her along with us to Salt Lake and make a wife of her when we got there. I asked if she was willing and she said, “Well she did not know, but that she would as soon have me for a husband as anybody that she knew.” So with that understanding she came and commenced to live with us and started with us while we resided in Nauvoo and started with us when we started to out West.

I will leave off here and take it up again in its proper place. I continued to work on the [Nauvoo] temple for several months longer, but I have forgotten the day when work ceased on it. On the 29th of April, 1845 I received the following certificate, the original of which is pasted in my scrap book:

“This may certify that George Morris is entitled to the privilege of the baptismal font, having paid his property and labor tithing in full to April 12th, 1846, City of Joseph, April 29th, 1846. William Clayton, recorder by James Whitehead, Clerk.

Soon after this the [Nauvoo] temple hands were called together by Orson Hyde, to see if they would be willing to consecrate 2/3 of the that was owing to them if he could succeed in raising enough money to pay them the balance, which we all readily consented to do. He, with the assistance of others, succeeded in raising the money and paid us accordingly. I received three gold sovereigns which made me feel like I was pretty rich as I had never before, all put together received to the amount of five dollars in cash for my labor in the four years and four months I had lived in Nauvoo.

The question t be asked then how did I live? I received flour, cornmeal, bacon, firewood, lumber, brick and now and then a little molasses. I got a little sugar a few times from Charles Allen for digging and tending his gardening nights and mornings after working all day on the brickyard. I bought my clothes all from England with me that I wore during that time with the exception of a few articles which my father sent me afterwards. I got married and had to start housekeeping under such circumstances; well how did I manage to do that? I had bought a bed and some bedding with me from England for my accommodation while crossing the sea. I also accommodated two other young men with me and I brought some dishes that I had while housekeeping in England. With a couple of quilts that my wife had managed to fix up a bed so to get along pretty well in that regard, I had money enough left to buy five hundred feet of lumber and I got the privilege to lean a shanty against the house that Brother William Anderson lived in, who was afterwards killed by the mob.

I was not able to get shingles to cover it with so I had to cover it with boards, and the roof being rather flat and the boards being pretty. When it rained it was a little worse than being out of doors. We got along pretty well with that rolling the bed up in as small a compass as we could and putting it in as dry a place as we could find and throwing something over it to keep it dry.

After a while we to be a little richer and we built a nice little brick house and we did not have to roll the bed up then to keep it dry. We were able to appreciate the difference between the two ways by experience, but we had no sooner began to appreciate the difference between the old shanty and our nice little brick house than we were compelled by the mob to dispose of it for anything that we could get for it. When an old Dutch widow lady came along and said, “I have 80 dollars for dat plaze.” I said, “You can have it notwithstanding that it had cost me between three and one hundred dollars.” She paid me the money and I took it and gave forty dollars of it for a Nauvoo made wagon. The other forty to the Nauvoo comnittee, Almond T. Babbit, Dad Fullmen and Joseph L. Haywood who had been appointed by the Twelve to dispose of Nauvoo property, for a large yoke of oxen and on the 12th day of crossed the Mississippi River on my way west.

Harriet, my wife’s sister started with us but having nothing in my wagon provided for our use while traveling I had to work for my outfit after we started. So I drove out about 12 miles west from the river into Iowa County and stopped in a neighborhood where two of my wife’s brothers lived, Abraham and James were their names. We stopped our wagon there a day or two and I went to hunt for work and ride arrangements to sink a well. I also engaged an old cabin that had been used as a stable situated about a mile distant from where they lived and fixed it up so that we could live in it. I sunk three wells in succession and had got what I thought for an outfit and was rejoicing over the prospect of being able in a few days to resume our journey but while I was engaged in finishing the well, at the top of the third well I was taken violently sick. In consequence of overanxiety of mind and governing myself, at that hard healthy business. The result was that I lay sick with the fever and ague for four months and five days.

Ser I was taken sick, my wife was confined with our second daughter. We named her Julia Ann. My wife did not do very well after her confinement. She was afflicted with the jaundice bad, when she began to get better from that, inflammatory residue settled in her knee and she was scarcely able to walk at all. Soon after a very large abscess broke out under her arm pit which deprived her of the use of her right arm for some time. I was almost helpless myself, I have seen many people with the ague but I never saw anyone as badly affected with it as I was. I would shake to the extent that the old cabin would shake too and the dishes on the shelf would rattle and I would turn black in the face and came near to suffocating often for want of breath. While in this condition one of my wife’s sisters, who was married and living some distance away came to visit her brothers. Together they came down to see us and she and her brothers bantered and tantalized Harriet so much about being my spiritual wife and calling her Mrs. Morris that she left us before we were able to wait on ourselves and went away with her sister. I had my oxen running on a piece of prairie land in front of the cabin tied head to foot so that they might not run away and where we could see then and keep watch on them.