Gilbert Belnap

/ Histories / Gilbert Belnap

Autobiography of Gilbert Belnap (1821-1846)

Typescript, HBLL

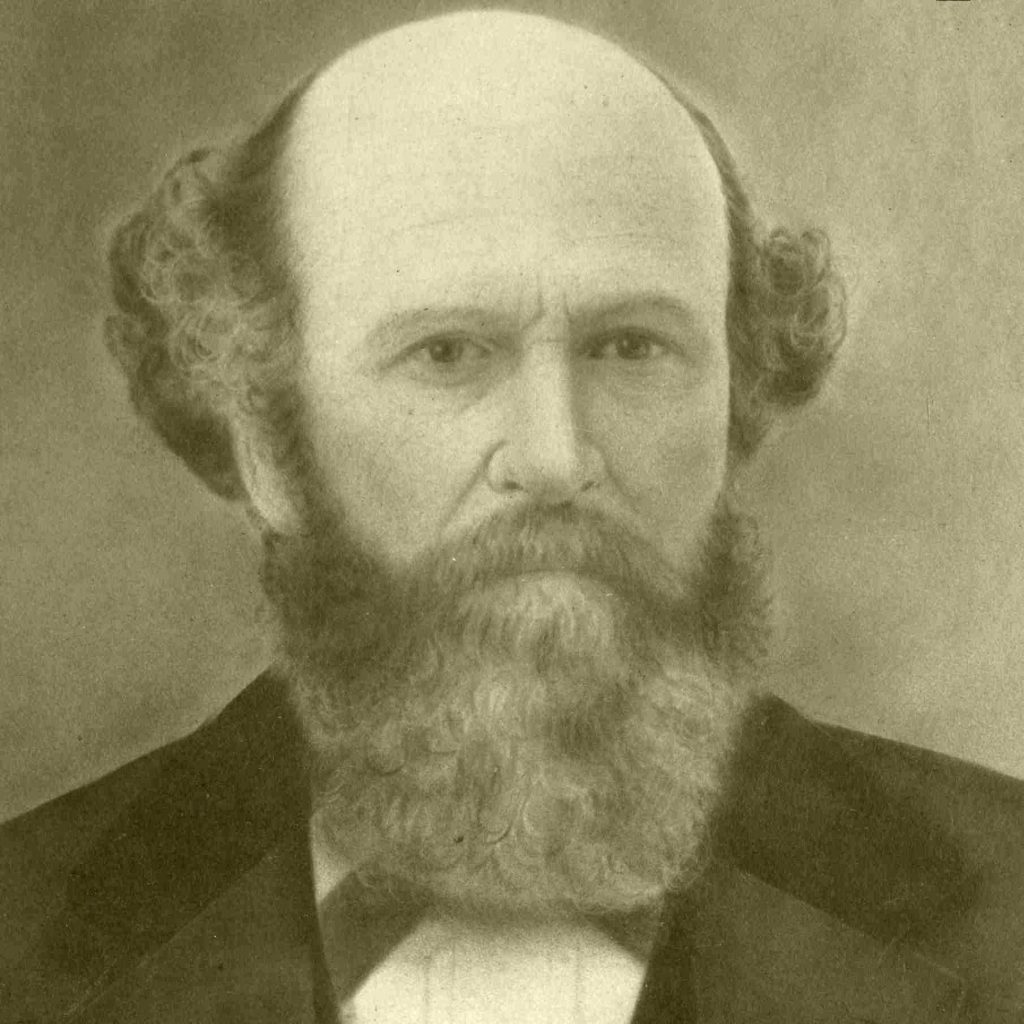

Gilbert Belnap

Gilbert BelnapPhoto Credit: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

I, Gilbert Belnap, am the son of Rosel and Jane Belnap, and was born in Hope, New Castle District, Upper Canada, on December 22, 1821. I am the third son of my father and the youngest of five children. Three sons were born after me, making eight in all.

At the age of ten years I was bereft of my parents. I had but little or no education, and according to the law of my native country, I was bound an apprentice to William C. Moore, who was a coach, carriage, stage and wagon maker by trade. He, through idleness and dissipation, became very much involved in debt, and accordingly left the country, not, however, without giving me a few days’ time to make a visit with my brothers and sisters. I did [not] understand the nature of his generosity at the time, neither was I made acquainted with his intended elopement until the night of his departure. I, being young and inexperienced in the world, was soon made to believe that I was, according to the articles of the agreement between us, under obligation to go with him beyond the boundaries of my native country. Accordingly in 1831, I was deprived of the society of my friends for a season. . . .

After listening to a long conversation between Abner [?] Cleveland and a man by the name of Colesburg about the locality of the town of Kirtland, and the beauty and construction of the Mormon Temple, prompted by curiosity and being of a roving disposition, I longed to form an acquaintance with that people and to behold their temple of worship. Accordingly, the third day after the conversation, I found myself on my way to see the wonders of the world constructed by the Latter-day Saints, commonly called Mormons. This edifice [Kirtland Temple] is built of rough hewn stone with a hard finish on the outside. It was divided off into solid blocks of equal size with a smooth surface resembling marble. Upon the east end stood the lofty spire with two rows of skylight windows on either side of the roof to light the apartments below. There were two large rooms on the first and second floors sufficiently large to comfortably seat two thousand people each. At each end of these rooms was a pulpit constructed for the purpose of accommodating those holding different degrees of the holy priesthood. The architecture and the construction of the interior of this temple of worship surely must have been of ancient origin as the master builder has said that the plan thereof was given by revelation from God, and I see no reason why this should not be credited for no one can disprove it. After a few days feasting my eyes on the products of Mormon labor, in company of William Wilson, I commenced a small job of chopping that he had taken. After its completion, I hired to C. G. Crary with whom I labored on a farm for eight months. During the winter I attended school.

The following winter I formed the acquaintance of several families called Mormons and by close observation satisfied myself that they lived their religion better and enjoyed more of the spirit of God than any other people that I had ever been acquainted with. Accordingly, I strove to make myself (acquainted) familiar with their principles of religion. After a diligent investigation for nearly two years, I satisfied myself with regard to the truthfulness of Mormonism and determined at some future date to obey its principles. Although I could not form any particular reason for deterring, so as I was of a wild romantic disposition, I could not immediately decide to embrace the religion of heaven and bring my mind and all the future acts of my life to corroborate with those divine principles. Yet, there was a sublimity and grandeur in the contemplation of the works of God that at times completely overshadow and cast to momentary forgetfulness the many vain amusements with which I had long been associated. Not being capacitated to being continually on the stretch of serious thought, my mind would again revert back upon the amusements of the world and being surrounded with the young and gay, I was easily drawn aside from the discharge of that duty, which my own better judgment prompted me to obey.

It has never entered my heart that many of the amusements which I had long been a participant were innocent in their nature and not offensive in the sight of God, only when made so by extravagance on the part of those who participated in them. Having little or no acquaintance with the Latter-day Saints prior to my arrival in Kirtland, the forces of my education had taught me to detest the slightest variation from morality in a religion of any kind. The minister that would participate in the dance or in many other amusements was discarded by his fellows and looked upon by the unbelieving world as a hypocrite and deserved to be cast without the kingdom. Why is that so? Simply because of their tradition and the force of education.

Prior to this time I had favored the Methodists and, complying with the requests of the priest, had sought the mourners bench and had strove with all my might to obtain the same manifestations of the spirit with which they said they were endowed. In spite of every exertion on my part in the honesty of my soul, I was compelled to acknowledge that I could not experience a similar manifestation to that which they, themselves professed to enjoy. From the deportment of this people, I soon became confirmed in the belief that the ministers only appealed to the feelings or the passions of the people, at least in many instances. I could form no other conclusion and felt disposed to leave them in the enjoyment of their supposed reality.

At this time, eighteen months had passed away since I had heard anything from my native country. After having written several letters, I at length received an answer from my brother John, who was then living in Whitly, Home District, W.C., bearing good news concerning all my brothers, and gave the whereabouts of my aged grandfather and mother. He also promised to meet me at their place of residence on the 10th of September, 1841. After complying with his request, I pursued my labors until two days prior to the time of our meeting. Then I set out and at the close of the third found myself in the presence of an old veteran of the Revolution whom I had long desired to see. After passing the usual compliments between two strangers, I craved his hospitality for the night which he has frankly granted. After evading as far as possible every question that related to my identity, not wishing to incur his displeasure, I, at length, told him who I was. I suddenly found myself surrounded by a numerous host of relatives.

The inmates of that house consisted of the aged couple, Jacob Alexander, his wife, the daughter of the aged pair, her son and two daughters of about 15 and 17 years of age. Their somber countenance and dignified appearance, together with their long faces made them look more like a group of Quakers to me than blood relatives of mine. A more religious man than Uncle Jacob I think I never had seen. Although there had been no mention made by men of my brother John’s expected arrival, I soon learned that he was looked for every hour, and that I was no unexpected guest. After the usual compliments on such occasions and a hurried recital of the time and place of my parent’s death and the whereabouts of the rest of the family, being fond of solitude, I retired to the back of the garden to consult my own feelings on the realities of what I had a few minutes before witnessed, for surely the place was adapted to the occasion for there the vine entwined around the shrubbery and the decaying foliage all bore unmistakable evidence of the new approach of those chilling blasts of the polar regions which bid the husbandmen to make ready for winter. I wondered if my newly formed acquaintance was destined to have any resemblance to the gathering of the grapes after the vintage is done, or should it be like the budding of the rose in early spring blossom and flourish in the rays of the sun for a season, and then with all its beauty and fragrance be like that portion of the vegetable kingdom with which I was surrounded at the approach of winter with away. I looked forward to the time of my admission into the kingdom of God as the only chilling blast that could possibly serve as an everlasting barrier between us, and like the rose, the approach of autumn return back to its native element.

While in this retired spot meditating on the prospects that were before me, my solitude was broken by the approach of my cousin, Serepta Alexander, who announced the arrival of my brother John. With her, I hurried back to the house to see him whom I had not seen for over three years and at the first embrace, could not refrain from shedding tears at meeting a brother whose life had been so dissimilar to mine. He had with determined purpose gained for himself the riches of this world which his hoarded thousands at this time abundantly indicated. While I detailed in my romantic way my life during the past few years, little did he think the future, or God, had a place in my thoughts and that I delighted in the perusal of sacred and profane history.

When in conversation with Uncle Jacob on the principles of religion, he learned that the wild boy was a scriptorian, and the old professor was far in the rear in point of argument which naturally disappointed that worldly brother of mine. After we had retired to rest, said he, “I fear you have become a Mormon.” I must acknowledge that this question somewhat startled me. Although I had not as yet attached myself to the Church, I plainly saw and experienced for myself the truth of that which I had heard the elders of Israel bear testimony that as soon as they embraced the gospel, they as a general rule were discarded by all their near relatives and were looked upon as a deluded fanatic, and that not one scriptural argument could be brought forth to convince them. In view of this truth and in answer to his question, I exclaimed, “Deliver me from lumbago and sour wine.” He asked me what I meant by that expression and I told him that although I was not a Mormon, I plainly saw that the followers of Christ in our day were like those of former times, hated for Christ’s sake and the testimony which they bore. I further told him, “If I am to be despised for the principles of religion which I advocate, I fear that our meetings will be few and far between, for I never have been the lad to be in anyone’s way.”

I continued visiting with my friends for about two weeks and from the time of my brother John’s and my separation at grandfather’s house we have never met again. At the present time fifteen years have rolled away without my seeing him.

After my return to Kirtland I continued laboring on the farm of C. G. Crary and extended the circle of my acquaintance with the people. I also exerted my mental faculties in searching out the principles of the gospel as taught by the Latter-day Saints.

During the winter of 1841, I met with a serious accident that fractured my skull in three places, dislocated my right shoulder and also my left ankle. The cause was unknown to me. I was confined to my bed from December 23 until April 13. During most of that time, I suffered the most acute pain. My acquaintances extended to me every mark of kindness within the power of mortals to bestow. To this day my good feelings are extended to one family of Mormons in particular, by the name of Dixon, for their kindness to me in my time of distress.

At this time, I well knew what my convictions were with regard to the truthfulness of Mormonism, yet I withstood and refrained from yielding obedience to the gospel which long before my better judgment had prompted me to obey. I had withstood those divine principles as long as I dared and preserved this mortal body above the ground. On April 12, I made a covenant with God before one witness by the name of Jeremiah Knight, that if he would raise me from this bed of affliction, I would obey his gospel; and be it known to all who may read these pages, that on the 13th of April, before alluded to, I had received sufficient strength in the short space of eight hours to harness and drive my own team three miles and be it also remembered that from the time of the disaster, I had not of myself sufficient strength to sit up in bed without the assistance of others. My sudden restoration of health created quite a sensation among the family of C. G. Crary, they being staunch Presbyterians. But old Jeremiah could easily divine the cause.

That season I continued my labors on the same farm enjoying as good health as I ever did in my life. Many of the Saints were curious to know why I did not join the Church after making so solemn a covenant before God, and received the desired aid. Yet strange to say such is the weakness of man and the imbecility of youth, although day by day I would tremble at the already procrastinated time; yet the evil traducer of man’s best interests was continually hedging up the way, and some vain transitory pleasure was constantly before my eyes; also the labors of the day and the increasing desire to gather around me some of the riches of the world inserted themselves into my mind and served as a barrier between men and the truth.

About June 20, 1842, I received a note requesting the attendance of myself and lady to a ball to be given in Menter at the home of Marvin Fisk on the 4th of July. In company with a number of others, I, at the appointed time, set out to amuse myself in the festivities of the day. We met at 10:00 a.m. and in the afternoon rode to Painesville to take dinner. Being among my associates, time passed off merrily. My joy increased when I compared this day with the first few days I spent as an exile three years ago.

Nothing transpired to disturb our peace until at the dinner table, I observed a heavy-set man of a dark complexion casting glances of malignant satisfaction at me. For a while I was puzzled to find his proper place, but finally decided, and in it was not mistaken. After I had conducted my lady to the sitting room and returned to the bar for a cigar, I found the fellow digging after me. Upon entering the room, said he, “Is your name Belnap?” “Yes, sir,” I replied, and “Is yours Chancy Dewiliger?” Said he, “Yes, by God, it is, so now you know the whole so prepare yourself.” Then each of us stripped for the onset, while the bystanders stared with amazement at our singular introduction. He said, “Follow me,” which I did, and as he stepped from the door to the pavement with vengeance beaming in my countenance and with clenched fist, I brought the fellow to his knees and I followed up my hand to the best possible advantage. He was not an able spectacle as many a scratch and bruise on my person loudly testified. The contest was longer and more fierce than I anticipated. Never did I want more anxiously for a man to cry for help than I did him, yet neither of us did at that time. At length we were parted by the crowd. After washing myself and purchasing a new pair of trousers and shirt, I concluded that I would not make a very beautiful appearance in company, and I would save my partner the mortification that her companion wore many a scratch and a black eye, by returning home. One thing bore with more weight on my mind than all others–I wanted him to bear the same news to his father that his father bore to him from the city of Buffalo, and I was determined he should if I had followed him to his place of destination. As soon as possible I made arrangements for my lady to be taken to the ballroom and from thence, home with her brother.

All being gone, I was left to my own reflections, when suddenly all the demons from the infernal regions seemed to counsel me to take that which I could not restore. Having a fruitful imagination I soon concluded upon a more mild but cruel attack. I then walked the back streets to pass away the time and avoid observation until sundown; then I returned to the hotel. The landlord informed me that young Dewiliger wished to speak to me. I asked him to tell him for me that I would see him in the morning when he little expected it.

After rising in the morning, I found that I was very sore about my chest which served to increase with redoubled energy my mode of attack. After washing my body in strong brandy and internally applying the same, I obtained some relief and at the first ringing of the bell, I was ready for breakfast. I there managed to seat myself opposite my antagonist. His grotesque motions with his head in managing to see what he had on his plate was truly laughable. A very little that morning satisfied my appetite for food, then I slowly raised up and placing one foot in the chair and the other in the middle of the table, quick as though, I sent the poor fellow backward and before any assistance could be rendered, he cried for help. Then I ceased my hellish efforts and immediately commenced the recital of the events that had transpired when I was a small boy and the scenes that had followed relative to that occurrence up to that time. And both proprietor and boarders accorded in the course that I had pursued, after the inhuman treatment I had received from the old man. In all my acquaintance with the family, I noticed that cruelty seemed to be a prominent characteristic of the entire family, and daily a deadly hatred continued to increase. From the time of this last occurrence, I have not seen one of this family.

After my last encounter with young Dewiliger, I returned home and was confined to the house for several days with the fever. When again I regained my former health, I wrote old man Dewiliger a very impertinent letter, and another to Marshal Stone setting forth the particulars of the encounter with Chancy Dewiliger, together with the result, and requested him set forth the truth of the matter to my old acquaintances. Thus far, this incident has terminated a cruel strife engendered in early youth, which I am in hopes will never be reasnimated [reanimated], for at present, peace is a great blessing and worthy of cultivation by man, which my experience for the last few years has taught me to fully appreciate.

When once able to pursue my usual employment, the query would often arise in my mind, “Shall I ever meet with any of that family and those long pent-up occasions burst forth with redoubled fury, and acts of cruelty and deeds of violence be resorted to to satisfy the promptings of ambition so common to humanity.” At present, I feel that I had satisfied every wrong that I had received, and concluded for the future to maintain amicable relations with them as long as such maintenance was a virtue, and if not, I resolved in my mind to prepare for the worst, let it come in what shape it would.

This last tragedy served to prevent me for a season from obeying the first principles of the Gospel, for I did not like to go into the waters of baptism with marks of violence on my person and stains of human blood on my garments, which I knew was sure to become a topic of conversation with many an idle gossip. Accordingly, day by day I pursued my labors on the old farm waiting for the storm cloud to pass on. As far as my own acts are concerned, I have a conscience void of offense pertaining to that unfortunate family.

Yet there was a secret monitor within my breast that would frequently warn me that delays were dangerous, and that I had better fulfill the covenant I had made with my God in the presence of one witness.

It is beyond the power of man to describe the contending emotions of my soul at that time– pride, pleasure, the speech of people, my accumulating interests, the frowns of newly-found relatives, and the appalling stigma attached to the word Mormon–were all obstacles that my youthful mind could scarcely surmount; and it was not until in solitude I unbosomed the contending emotions of my soul to God that I found relief and peace, and the gentle whisperings of the spirit of God prompting me to forthwith obey the truth which on the next day I determined to do. That night in my sleep, I frequently awoke and found myself preaching the Gospel to different nations of people.

Time passed on rapidly until the time arrived to prepare for baptism. Sunday, September 11, 1842, was a time long to be remembered by me for in the presence of a vast multitude of saints and sinners, in company with William Wilson, I yielded obedience to the Gospel, though long before this time, I had been sensible that it was my duty to do so. Some tossed their heads in scorn, while others found a friend and brother. In these acts of derision, I was not disappointed for I had by observation learned that fact long before. It may seem strange to the unprejudiced reader why and how it is that in this boasted land of liberty and equal rights where all men have the constitutional right to worship God as best suits their own feelings that this condition exists. Yet in the nineteenth century, there is one class of people called Latter-day Saints that by priest and people, governor and ruler, are denied this estimable privilege. In the history of this Church, there is abundant testimony to this fact which I shall have occasion to refer to in relating my experiences.

After joining the Church, I strove with determined purpose to keep the commandments of God. Accordingly, I deprived myself of many amusements which before this time I had been an extravagant participator in, and with full purpose of heart, devoted my time and talents to the service of the Lord. Although I was young and bashful in the expression of thought, barren and unfruitful in the knowledge of God and unacquainted with the principles of the Gospel, yet, having been ordained under the hands of an apostle of God in the last days, I determined to know of the restoration of the Gospel, and to qualify myself to discharge the duties incumbent in a man of God in proclaiming the same to the inhabitants of the earth. . . .

At length, the time appointed to start a new career in life, and I bid adieu for a season the friends made dear to me through association. Though I was accustomed to traveling, never before was I dependent on the charity of a cold world for my daily bread. Heretofore the few shining particles I carried with me were sure to secure friendship. But now, how changed the scene. After many fruitless attempts to secure shelter for a single night from the chilling blasts of winter, I was many times compelled to rest my weary limbs in some open shed or loft of hay. Out there hungry and shivering, I would pour out my soul to God.

Day by day we pursued our course preaching by the way as opportunity would permit and the people came to hear. In many places we were kindly received, doors were open and men of understanding sought both in public and private to learn the doctrines of the Latter-day Saints. While others for the sake of controversy and the love of discord would intrude upon the congregation by asking many discordant questions and when met by simple truth and stern realities, were compelled to acknowledge that one fact clearly demonstrated was worth ten thousand theories and opinions of men.

At times discussion of this kind would prove of real benefit but in other cases when the speaker for the people was completely confounded and put to an open shame, a deep settled prejudice which our own personal wants would fully realize, for we had to contend with the prejudice of the ignorant, of the learned.

While traveling one day, we drove up to the door of my uncle, who a few months before had taken much pains to convince me of the error of my ways. Unluckily he was not at home, being absent in the discharge of his ministerial duties. I remained in that neighborhood three days and three times in grandfather’s house preached to a crowded congregation, consisting principally of my kin folks. During this time my comrade had continued his travels to Evansville, New York, where I joined him after the space of many days. While here, through indefatigable energy, we baptized persons from a lukewarm state to a lively sense of their duty. We organized a small branch of the Church by ordaining Elisha Wilson an elder, and Charles Utley a priest and Albert Williams a teacher. When we left there they were in possession of many of the blessings of the Holy Spirit. . . .

. . . Our labors were principally confined to Steuben, Livingston, Ontario, Genesee, Erie, Chautauqua, Cattaraugus and Yates Counties until after the spring rains. Duty demanded that one of us go to St. Lawrence County. The lot fell to me to remain in our old field of labor. While my partner left to find new associations, I remained in the regions round about until the middle of the next summer when because of my health, I returned home.

I had, in connection with my partner, baptized over seventy persons. I am happy to say that at present several of the Saints from that section of the country are now located in the valleys of the mountains. . . .

I remained in this place and the surrounding country for two months. I again met Elder John P. Greene on his way to Nauvoo. From here, I returned to Kirtland and attended school, taught by O. H. Hanson, and boarded with the family of Reuben McBride.

Early in the spring of 1844, I helped to build two small barns for T. D. Martindale and one for James Cower. They were completed on the fifteenth of May. I set out for Nauvoo in company with Elarson Pettingill and Henry Moore with Christopher Dixon, wagoner, as far as Wellsville on the Ohio River, at which place he returned back to Kirtland. We embarked on board the steamboat Hehi, for St. Louis, Missouri.

I had not been on board long, when I learned there were others belonging to the same faith as myself and bound for the same place of destination. They, however, for the want of means, would be compelled to stop in Cincinnati. I proposed to pay their passage if they, after landing as soon as circumstances would admit, would restore to me the amount that I had expended for their benefit. I had in charge at that time three tons of groceries donated toward the building of the Nauvoo Temple, which I had found in store at Wellsville, and under the direction of Lyman Wight, was to take them through.

On the first day of June, 1844, late in the evening, I arrived in the delightful city of Nauvoo without a single cent in my pocket. After securely storing the goods in the ward house, I laid myself down to rest in the open air upon a naked slab.

June, the second, early in the morning, I found myself on the streets of Nauvoo, the evening before, Petingale [Pettingill] had agreed to meet me at the residence of the Prophet Joseph at nine A.M. Observing and reflecting upon everything I saw and heard, I slowly pursued my course to the mansion of the Prophet. That day passed away, and Petingale did not appear. Morning came and went, and not one face that I had ever seen before could I recognize as I walked the streets.

I viewed the foundation of a mighty [Nauvoo] temple with the baptismal font resting on the backs of twelve oxen, probably the first one built since the days of Solomon. I then went to the stone cutters shop, where the sound of many workmen’s mallets and the sharpening of the smith’s anvil all bore the unmistakable evidence of a determined purpose to complete the mighty structure.

I then returned to the mansion of the Prophet and after a short conversation with the bartender, who I afterwards learned was Oren Porter Rockwell, to my great satisfaction, I saw Petingale [Pettingill] and five others about to enter the building. After greeting my old friends heartily, I was introduced to the Prophet, whose mild and penetrating glance denoted great depth of tough and extensive forethought. While standing before his penetrating gaze, he seemed to read the very recesses of my heart. A thousand thoughts passed through my mind. I had been permitted by the great author of my being to behold with my natural eyes, a prophet of the living God when millions had died without that privilege, and to grasp his hand in mine, was a privilege that in early days, I did not expect to enjoy. I seemed to be transfigured before him. I gazed with wonder at his person and listened with delight to the sound of his voice. I had this privilege both in public and private at that time and afterwards. Though, in after years, I may become cast away, the impression made upon my mind at this introduction can never be erased. The feeling which passed over me at this time is impressed upon me as indelibly and lasting as though it were written with an iron pen upon the tablets of my heart. My very destiny seemed to be interwoven with his. I loved his company; the sound of his voice was music to my ears. His counsels were good and his acts were exemplary and worthy of imitation. His theological reasoning was of God.

In his domestic circle, he was mild and forbearing, but resolute, and determined in the accomplishment of God’s work, although opposed by the combined powers of earth. He gathered his thousands around him and planted a great city which was to be the foundation of a mighty empire and consecrated it to God as the land of Zion. At the same time, he endured the most unparalleled persecution of any man in the history of our country. Like one of old, the arms of his hands were made strong by the hands of the mighty God of Jacob. With a mind that disdained to confine itself to the old beaten track of religious rites and ceremonies, he burst asunder the chains which for ages past had held in bondage the nations of the earth. He soared aloft and brought to light the hidden treasure of the Almighty. He bid defiance to the superstitious dogmas and the combined wisdom of the world and laid the foundation for man’s eternal happiness and revived the tree of liberty palsied by the withering touch of Martin Van Buren.

Thus, the first few days of my residence in Nauvoo was passed in forming new acquaintances, and greeting the old friends I chanced to meet. I soon became a workman in the shop of Thomas Moore and boarded at the home of John P. Greene.

I was frequently called out by the Prophet Joseph to the performance of various duties. I did not regret the time spent on such missions as I considered them schools of experience to me. I will refer to one among many similar to it that I performed in those days.

There was to be held a convention of anti-Mormons in Carthage. I was required by the Prophet to form one of their number. With a promise of my fidelity to God, he assured me that not a hair of my head should fall to the ground, and if I followed the first impressions of my mind, I should not fail in the accomplishment of every object that I undertook. At times, when all human appearance, inevitable destructions awaited me, God would provide the means of escape.

When first I entered Carthage, I was interrogated by Joseph Jackson, Mark Barns, and Singleton as to what business I had there. I replied that I had business at the recorder’s office. They, being suspicious of deception, went with me to the office. After examining the title of a certain tract of land, many impertinent questions were asked me, which I promptly answered. Then, a low-bred backwoodsman from Missouri began to boast of his powers in the murder of men, women and children of the Mormon Church and the brutal prostitution of women while in the state of Missouri and that he had followed them to the state of Illinois for that purpose. Without considering the greatness of their numbers, I felt like chastising him for his insolence. Just then, he made a desperate thrust at my bowels with his hunting knife, which penetrated all my clothing without any injury to my person. Nerved, as it were, with angelic power, I prostrated him to the earth, and with one hand seized him by the throat, and with the other drew his knife. Had not Jackson grasped me by the arm between the hand and elbow, throwing the knife many feet in the air, I should not deprived him of his natural life. Although my antagonist was still insensible, the prospects for my becoming a sacrifice to their thirst for blood were very favorable. Had not Jackson and others interfered in my behalf, it would have been so.

I afterward sat in council with delegates from different parts of the country and secured the resolutions passed by that assembly. I then returned in safety to Nauvoo, but not without a close pursuit by those demons in human shape, uttering the most awful imprecations, and bawling out to meet almost every jump to stop or they would shoot. My greatest fear was that my horse would fall under me. I thought of the instance of David Patton administering to a mule which he was riding when fleeing before a similar band of ruffians. I placed my hands on either side of the animal and as fervently as I ever did, I prayed to God that his strength might hold out in order that I might bear the information which I had obtained to the Prophet. There were no signs of failure in accomplishing this purpose until just opposite the tomb. My horse fell on his side in the mud. This seemed to be a rebuke for me for urging him on to such a tremendous speed. We were entirely out of danger and covered with mud by reason of the fall. I rushed into the presence of the Prophet and gave him a minute detail of all that had come under my observation during that short mission, whereupon W. W. Phelps, then acting as notary public, was called in and my deposition taken with regard to the movements of the people. Daniel Carns was deputed to bear this information to the governor, Thomas Ford.

The people of Carthage, being suspicious of more men being sent as spies, waylaid the road and arrested Carns and took from him the deposition. In this way, my real name was known among the bitterest enemies of the Saints. This discovery subjected me to many privations caused through continual persecution. Before and after this time, frequent dissensions took place in the Church and political factions arose. Willful misrepresentations and calumny of the foulest kind were circulated with untiring zeal among the uncouth and ignorant. These, with writs of various kinds, were used to drag a man from the bosom of his friends. The very elements seemed to conspire against the Saints. That mighty engine, the press, with all its powers of dissimilation, was arrayed against them. The public arms were demanded in order to weaken the Saints’ power to resist when invaded. Every artifice was resorted to, to accomplish the destruction of the Prophet.

When the storm cloud had lowered around the Prophet’s head and the contending emotions of the discordant political factions surrounded him on every side, he set forth with determined purpose to fill his mission in an acceptable manner before his God and maintain the identity of the Saints. He upset the table of the money changers and set aside the tippling shop. In the fervency of his soul in connection with the common council, he declared the Nauvoo Expositor Press a nuisance. The city marshall, with a chosen band of men, fulfilled the decree of that council and disabled that the mighty engine of knowledge appropriated for the seduction of the Saints.

In the midst of these contending factions, it was as impossible for the Saints to reason with the people as it was for Paul to declare the glad tidings of a crucified Christ and a risen Redeemer when the air was rent with the cry of “Great is Diana of the Ephesians.” Under existing circumstances, what was to be done? How were we to correct the public mind? Our means of giving information was very limited. We might as well attempt to converse with the drunkard while he reels to and fro under the influence of intoxicating poison, or lift up our voice to the tumultuous waves of the ocean, or reason amidst the roar of ten thousand chariots rushing suddenly along the pavement, as reason with the people, for great was the universal cry, “Mormonism is a delusion, phantom,” and so forth.

At length the evil day appeared and the dark cloud burst with fury over the Prophet’s head. He appeared once more at the head of his favorite [Nauvoo] legion. They, however, surrendered the public arms and he gave himself a sacrifice for the people. Well I remember his saying, referred to in the latter part of the Doctrine and Covenants [D&C 135:4]. “Although I possessed the means of escape yet I submit without a struggle and repair to the place of slaughter.” Where he said he would yet be murdered in cold blood.

I saw the forms of court and heard the many charges against him which were refuted by plain and positive testimony. After this, he was committed to jail upon false accusation and myself and others lodged there with him.

During the time of his mock trial, he received the promise of protection from Thomas Ford, then governor of the state, and that he would go with him to Nauvoo. The governor went to that place without fulfilling this promise.

After his departure, the few Saints that were left in Carthage were expelled at the point of the bayonet, not, however, until the Prophet, from the jail window, exhorted them for the sake of their own lives to go home to Nauvoo. I well remember those last words of exhortation, and the long and lingering look on the den of infamy for I did not consider that safe with such a guard. Thus, the Prophet, his brother Hyrum, Willard Richards, and John Taylor were left alone in the hands of those savage persons.

The afternoon previous to the martyrdom, we hurried to Nauvoo to announce the coming of the Prophet as was agreed by the governor [Thomas Ford]. But with him came not the beloved Prophet which soon convinced the people that treachery of the foulest kind was at work. This cowardly, would-be-great man tried his best to intimidate the people. It was with difficulty, however, that some few could be restrained from making sad havoc among his troops. Had the Saints known the extent of his treachery, I am of the opinion that Nauvoo was of short duration, for well he knew the deep designs against the Prophet’s life.

On his return to Carthage, he met George D. Grant bearing the sad news of the slaughter at the jail, whereupon the cowardly curse arrested Grant and took him back to Carthage in order to give himself time to escape. Thus, the distance of eighteen miles was travelled over three times before the sorrowful news of the Prophet’s death reached his friends.

In the afternoon of June 26th, the mournful procession arrived bearing the mangled bodies of the Prophet and the Patriarch and Elder John Taylor. Although the latter still survived, he mingled his with the best blood of the century. Willard Richards escaped without a hole in his garment. Their bodies were placed in a commodious position and the assembled thousands of Saints gazed in mournful silence on the faces of the illustrious dead.

While penning these few lines, tears of sorrow still moisten my cheeks and I feel to hasten to the recital of other events.

At this time, many of the Twelve Apostles and the principle elders of the Church were absent on missions. As soon as possible when they heard of the awful tragedy, they returned home to Nauvoo. Truly the state of affairs was lamentable. A whole people were apparently without a leader and like a vessel on the boisterous ocean, without a helm.

In a few days, Sidney Rigdon arrived from Pittsburgh and set up his claims as guardian of the Church. Diversities of opinion prevailed among the people. In a meeting of the Saints, Brigham Young, then president of the Quorum of the Twelve, from a secluded retreat, appeared on the stand. There, in plainness and simplicity, he proved himself by ordination from the Prophet to be his legal successor. This is confirmed by Orson Hyde and other members of the Twelve.

After the above demonstration of facts, Rigdon appeared no more in public to vindicate his claims for guardianship, but by secret meetings and private counsels, strove to gain his point. Notwithstanding his power of eloquence, he loaded himself with eternal infamy and returned in disgust to Pittsburgh, leaving a firm conviction in the minds of the Saints that he completed his own ruin.

After this, the Saints enjoyed a short respite from cruel strife but not without an almost endless drain of their substance by continued suits at law imposed on them by the ungodly. With united efforts, however, they strove to complete the [Nauvoo] temple of worship which they desired to do if permitted by their enemies. Should they not complete the temple, the Saints, according to the revelations of God [D&C 124:30-33], were to be rejected together with their dead, but thanks to God, their work was acceptable and many were permitted to receive their endowments.

Again, because of the prosperity of the Saints, the fire of persecution was kindled in the summer of 1845, and the blaze of torment was applied to many a house and sack of grain, and whole settlements were driven into Nauvoo, destitute of the comforts of life and some were shot down in the presence of their families and everything they had consumed by fire.

This state of affairs continued to grow worse until the leaders, in order to preserve the identity of the Church, were compelled to endorse articles of agreement to leave the country as soon as possible.

In the month of February, 1846, the western shore of the Mississippi was covered with the companies of the Saints. Some had covers drawn over their wagons while others had only a sheet drawn over a few poles to make a tent. Sometimes these rude tents were the only covering for the invalid forms of the unfortunate. Many was the time, while keeping the watchman’s post in the darkness of the night when the rains descended as though the windows of heaven were open, have I wept over the distressed condition of the Saints. Toward the dim light of many a flickering lamp have my eyes been directed because of the crying of children, the restless movements of the aged, infirm and mournful groan of many suffering from fever. These have made an impression on my mind which can never be forgotten. . . .