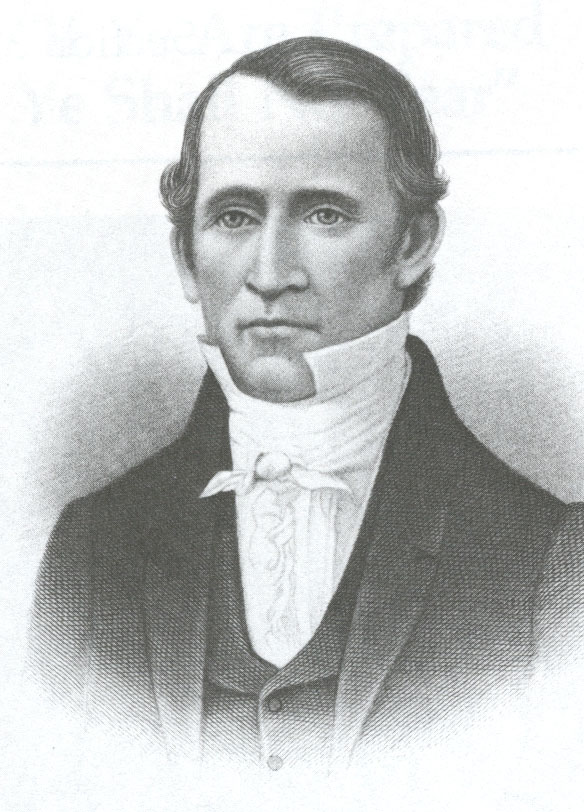

Edward Partridge

(1793-1840)

By Susan Easton Black

Edward learned the hatter’s trade in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. By 1830 he had his own hat shop on the public square in Painesville, Ohio. Edward prospered in his vocation but wanted more out of life. He attended Universalist and Unitarian meetings, hoping these religious societies would satisfy his yearnings for truth. His wife Lydia found Campbellite worship services more to her liking. The couple’s religious differences ended in the fall of 1830 when missionaries from the Church of Christ preached in their neighborhood. Although Edward was not initially impressed by their Restoration message, he sent an employee to acquire a Book of Mormon for him.

After reading the Book of Mormon, Edward believed the book to be the word of God but declined to be baptized. Yet, in winter of 1830 he left Ohio and journeyed to New York to meet the Prophet Joseph Smith. The day after meeting Joseph, on December 11, 1830 Edward entered baptismal waters. He returned to Ohio rejoicing in his newfound faith.

Edward was called to the first Bishop of the Church, “and this because his heart is pure before me, for he is like unto Nathanael of old, in whom there is no guile” (D&C 41:11). In a letter to his wife written in Independence, Missouri, Edward expressed his personal feelings of inadequacy: “You know I stand in an important station, and as I am occasionally chastened. I sometimes feel my station is above what I can perform to the acceptance of my Heavenly Father.”1 In spite of such feelings, Edward was up to the task. When misunderstandings and tensions escalated between the Latter-day Saints in Independence and longtime Missourians, Edward stepped in to calm the situation. Angered by his mediation attempts, Missourians took him from his home and physically abused him. Edward wrote of July 20, 1833,

I was taken from my house by the mob . . . who escorted me about half a mile, to the courthouse, on the public square in Independence; and then and there . . . I was stripped of my hat, coat and vest and daubed with tar from head to foot, and then had a quantity of feathers put upon me, and all this because I would not agree to leave the county, and my home where I had lived two years. . . . I bore my abuse with so much resignation and meekness, that it appeared to astound the multitude, who permitted me to retire in silence, many looking very solemn, their sympathies having been touched. And as to myself, I was so filled with the Spirit and love of God, that I had no hatred towards my persecutors or anyone else.2

Three days after being tarred and ſeathered, Edward saw mobs again gather on the public square. To prevent further abuse and threatened bloodshed, he signed a document promising to leave the county. To avoid further mob brutality, for five nights Edward and his family camped near the Missouri River before being ferried across the river to safety in Clay County. As other Saints experienced similar abuse, Edward wrote to the Prophet Joseph Smith, “Many are living in tents and shanties not being able to procure houses.”3 During these difficult days, Edward moved about from tent to shanty providing comfort to the discouraged Saints.

From Clay County, Edward and his family moved to Far West, Missouri, where once again religious persecution went unchecked. “The soldiers took my hay and corn,” Edward wrote. “They also took logs from a hovel I had been building for my cows and burnt them. The town was nearly stripped of fence.” Edward was imprisoned in Far West and charged with treason, arson, burglary, robbery, and larceny. He awaited trial in Richmond in “a large open room where the cold northern blast penetrated freely. Our fires were small and our allowance for wood and food was scanty, they gave us not even a blanket to lie upon; our beds were the cold floor. The vilest of the vile did guard us and treat us like dogs; yet we bore our oppressions without murmuring.”4 He was released on November 28, 1838.

As threats against him mounted, Edward fled with his family from Missouri to safety in the barge town of Quincy, Illinois. In March 1839 the Prophet Joseph Smith wrote from Liberty Jail to the Latter-day Saints and to “Bishop Partridge in Particular” a message of hope and the stirring accounts contained in Doctrine and Covenants, Sections 121, 122, and 123.

Edward suffered a different type of affliction in Illinois. On June 13, 1839 he wrote of poverty and failing health:

I have not at this time two dollars in this world, one dollar and forty-four cents is all. I owe for my rent, and for making clothes for some of the poor, and some other things . . . What is best for me to do, I hardly know. Hard labor I cannot perform; light labor I can; but I know of no chance to earn anything, at anything that I can stand to do. It is quite sickly here.5

Edward joined the Prophet Joseph and other Latter-day Saints in moving from Quincy to Commerce, Illinois. There he was assigned to be the bishop of the “Upper Ward.” Unfortunately, his service to those residing in the Upper Ward was brief. While building a home for his family, Edward collapsed from exhaustion and took to his bed. He died on May 27, 1840 at age 46. In Doctrine and Covenants 124:19 the Lord revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith that he had received Edward Partridge “unto myself.”

1. Edward Partridge Jr., Biography and Family Genealogy. Unpublished Journal (Salt Lake City: n.p., 1878), pp. 6-7.

2. History, 1838-1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805-30 August 1834]. p. 327. Joseph Smith Papers.

3. Partridge Jr., Biography and Family Genealogy, p. 9.

4. Ibid., pp. 52-53, 57.

5. Journal History of the Church, June 13, 1839.

Additional Resources

- Biography of Edward Partridge (josephsmithpapers.org)