Revelations and Translations |

Episode 3

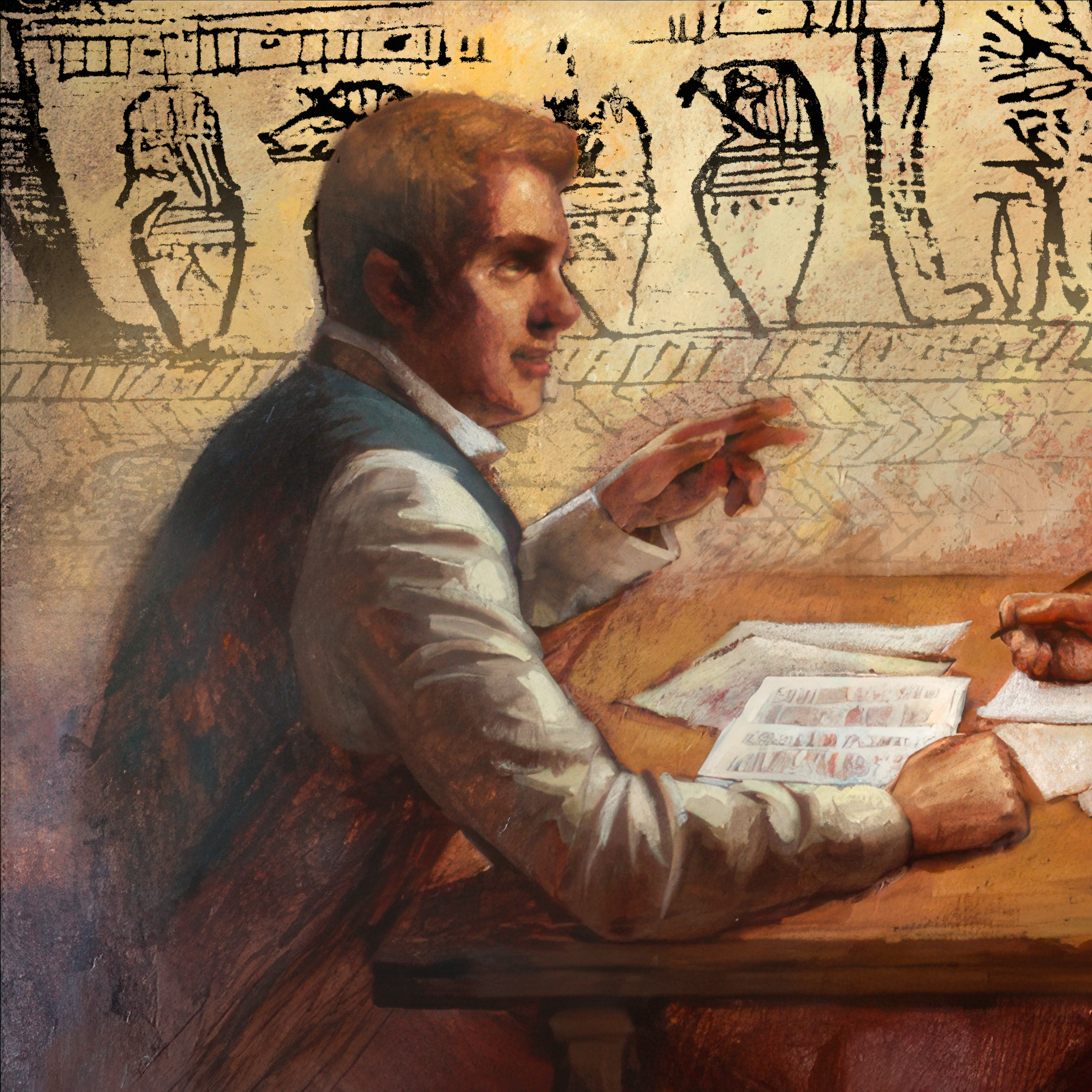

Did Joseph Smith Plagiarize Part of the JST?

60 min

In his Bible translation project, did Joseph Smith plagiarize the work of a prominent British scholar named Adam Clark? Or, if you don’t want to call it plagiarism, did Joseph Smith borrow or appropriate phrases or ideas from Adam Clark’s Bible commentary without attribution which are found in our JST footnotes today? This is the question at the heart of the biggest modern controversy surrounding Joseph Smith’s Bible translation. In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we trace the origins of this controversy back to a series of interviews and articles by BYU professor Thomas Wayment and his research assistant Haley Wilson-Lemmon, beginning in 2017 and culminating in a book chapter published in 2020. And, as we are inclined to do with all things related to Joseph Smith’s Bible translation, we’ll look to expert Kent Jackson for his take on the claims of Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon in an article he published as a critique and refutation of their research.

Revelations and Translations |

- Show Notes

- Transcript

Key Takeaways

- Thomas Wayment and Haley Wilson-Lemmon wrote two papers asserting that the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) of the Bible was influenced by British scholar Adam Clarke’s commentary, citing similarities between the two works.

- Initially, this theory was seen as a minor scholarly development, as it aligned with Joseph Smith’s practice and teaching of being open to truth, whatever its source.

- The discussion became a controversy when Wilson-Lemmon left the church and appeared on several podcasts that asserted that Joseph Smith’s alleged use of Clarke’s commentary amounted to plagiarism.

- Since her appearance on the podcasts, Wilson-Lemmon has said “We can’t call what Joseph Smith did plagiarism. Everyone will see it differently, and that’s fine. The point is that Joseph Smith used Clark for his JST, and regardless of what you want to call it, that fact cannot be denied.”

- In an exhaustive paper, Kent Jackson explored each citation addressed by Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon’s paper and disagreed with their findings, saying that the examples were not notable enough to show a connection between the Joseph Smith Translation and Adam Clarke’s commentary. He also asserted that the charge of plagiarism has been amplified by critics of the Church, including Wilson-Lemmon, for their own purposes.

- The controversy surrounding Joseph Smith’s use of Adam Clarke’s commentary has been distorted and exaggerated. It is vitally important that we critically examine such claims before embracing them.

Related Resources

Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith’s Translation Projects in the Development of Mormon Christianity, Eds. Michael Hubbard MacKay, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Brian M. Hauglid

Kent Jackson, “Some Notes on Joseph Smith and Adam Clarke,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 40 (2020)

Scott Woodward:

Hi. This is Scott from Church History Matters. Because we’re at a point in this series where we’re about to move away from the topic of Joseph’s Bible translation, we thought it might be helpful to pause mid-series and spend our next episode taking any questions you might have about Joseph’s Bible translation project. We will be pleased to have as our special guest Dr. Kent Jackson to help us respond to your questions. He’s an author and scholar on all things related to Joseph’s Bible translation, and Casey and I have drawn. heavily from Dr. Jackson’s excellent research throughout this series so far. So please submit your thoughtful questions anytime before September 6, 2023 to podcasts@scripturecentral.org. Let us know your name, where you’re from, and try to keep each question as concise as possible when you email them in That helps out a lot. OK. Now on to the episode. In his Bible translation project, did Joseph Smith plagiarize the work of a prominent British scholar named Adam Clark? Or, if you don’t want to call it plagiarism, did Joseph Smith borrow or appropriate phrases or ideas from Adam Clark’s Bible commentary without attribution which are found in our JST footnotes today? This is the question at the heart of the biggest modern controversy surrounding Joseph Smith’s Bible translation. In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we trace the origins of this controversy back to a series of interviews and articles by BYU professor Thomas Wayment and his research assistant Haley Wilson-Lemmon, beginning in 2017 and culminating in a book chapter published in 2020. And, as we are inclined to do with all things related to Joseph Smith’s Bible translation, we’ll look to expert Kent Jackson for his take on the claims of Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon in an article he published as a critique and refutation of their research. So this should be fun. I’m Scott Woodward, and my co-host is Casey Griffiths, and today we dive into our third episode in this series dealing with Joseph Smith’s non-Book-of-Mormon translations and revelations. Now, let’s get into it. Hello, Casey.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Hello, Scott. How are you doing?

Scott Woodward:

Doing so good. How about you?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Very good. I’m excited to talk about our topic today. I’ve done kind of a deep dive into this over the last couple of days. I’m loaded for bear, and I’m ready to go in there, so.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. You know, that’s probably good for our listeners to hear: that what we do as we prepare is we, like, load up like crazy on our topic, and then once we, like, talk through it—I don’t know: If you asked us in two months from now to talk about these things cold, like, we probably couldn’t with the same amount of—you probably could, Casey, because you’ve got such a sharp memory.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I don’t know.

Scott Woodward:

But yeah, sometimes I’ll listen to our old podcast, and I’ll think, like, ”I don’t even remember that point. That was”—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, me too. Me too. Sometimes I listen to it and go, “Hey, that was pretty good.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“And I don’t remember making those points.”

Scott Woodward:

That’s right. Yes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But the point is we’re learning.

Scott Woodward:

That’s right. Yep. We’re learning, and we’re trying to then pass that on.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So we’ve been talking about the Joseph Smith Translation, and last time we talked about the tight, interwoven relationship between the JST and the Doctrine and Covenants.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And a few key points we pointed out: I think probably the most important thing that we mentioned last time is we proposed, and I think we are both united on this—we feel good about this, that possibly the primary purpose of the Joseph Smith Translation was to provide Joseph Smith with a springboard to receiving additional revelations that would spur on the rest of the Restoration.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

That is, as Joseph Smith translated the Bible, he was then led to ask the Lord important questions sparked by the text, the answers to which were then recorded and published in the Doctrine and Covenants. And so the JST acts as a springboard to additional D&C revelations, and we think there’s really good evidence for this.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

For instance, we mentioned that about half of our Doctrine and Covenants today came during that time period that Joseph was translating the Bible from June 1830 to July 1833, with many of those revelations coming directly from the Joseph Smith Translation. And what’s interesting and kind of peculiar about those D&C sections that are influenced directly by the Joseph Smith Translation is that they all seem to be consistently doctrinally rich, and they’re nearly always dealing with really important matters of, like, eschatology, meaning like the end of the world and beyond type of stuff, or matters from like the ancient past about Adam or Abraham or the Patriarchs or Israel or whatever.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And we discussed several examples of that. We mentioned Doctrine and Covenants 29, the very first kind of big, grand revelation about the Millennium and the redemption of the world and the sanctification of the earth. Like, all of that comes because they’re discussing JST, recent translations.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

D&C 37, 38, and 42, 65. The big kahuna was 76, and 132. We also mentioned 93. There’s several other examples, but one point we really tried to drive home was how much church history was directly influenced by the Joseph Smith Translation, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

For instance, the gathering of the New York Saints to Ohio 1831, and then subsequently many of the saints going to Missouri in pursuit of Zion, the new Jerusalem, a major theme of Moses six and seven.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

The practice of living the law of consecration directly comes out of that. The idea of Adam and Eve as models of reinheritance into the family of God for the rest of us. This is going to be a familiar theme, which will become ritualized in Nauvoo into the temple.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm. Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

The concept of the high priesthood, or the Melchizedek priesthood, and its restoration in Kirtland grows right out of Genesis 14. The understanding of the keys of the priesthood and their connection to directing the Kingdom of God on Earth comes directly from a question Joseph had about the Lord’s Prayer, right? Matthew 6:10 and D&C 65 was given as a result.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

You pointed out the practice of baptism at eight years old. We first learned that in the JST, that that’s the age of accountability. Then later baptism is commanded to happen at the age of accountability.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

The practice of plural marriage. If that didn’t affect our church history, I don’t know what did.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

D&C 76. The massively expanded conceptualization about God, his merciful plan of salvation for all mankind, and our understanding that we can actually become like God. D&C 93.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

A lot of people think that’s, like, a Nauvoo idea that Joseph doesn’t begin teaching until Nauvoo, but we see it right there in D&C 93, that we can gain the fullness like Christ did. That’s early, right? And that comes right from Joseph Smith’s work on the JST.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So we’re not talking little footnotes in your scriptures, right? We’re not talking, like, “Oh, that’s a neat little insight, right? That’s kind of how it was for me growing up. As you look down, the footnote in the Bible, and there’d be this little “JST,” and it would kind of clarify a word or a phrase.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

Might be a little idea. And there’s some of that, but what we talked about last time was the most profound influence of the Joseph Smith Translation on the Doctrine and Covenants, and then subsequent, like, church history that then actually plays out in time and space and that we’ve been directly affected by in our history.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Anything you want to add to that review?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Just that it’s surprising how important the Joseph Smith Translation is to our theology and our belief.

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I mean, I think when Latter-day Saints try to spell out what makes us different from other Christians, we go directly to the Book of Mormon, and that’s a good place to start.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But a lot of our fundamental differences are things that come from the JST, particularly those JST sections that are in the Pearl of Great Price. It’s just hard to underestimate how important that is towards our worldview, our view of humanity, and most importantly, our view of God and Jesus Christ, so this is sort of something that even Latter-day Saints maybe don’t fully appreciate: that Joseph Smith’s work on the Bible was hugely important in forming what we are

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And what we believe today.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. It’s incredible. And like we said to begin with, like, this is insightful. As we’ve done a deep dive, for the both of us, like, I think it’s—it’s just been insightful to even just talk about it out loud with you and realize I don’t know if I fully appreciated the impact of the JST on our theology, on our temple liturgy, on our church history, ultimately how that has impacted who we are and what we stand for, so. Very cool.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s huge, right?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And one of the things that we’ve continually noted about the JST is part of what makes it complex is it wasn’t really finished. Joseph Smith does complete a round of translation by 1833. He never is able to publish it in his lifetime. And I guess we would add, too, that the controversies surrounding the Joseph Smith Translation are not finished either. Today we’re going to talk about a controversy that has sprung up in the last couple years.

Scott Woodward:

Yes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

You may or may not have heard about this. Most of my students, I find, have not heard about this.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Let me tee it up, then. So here’s the question: What is the biggest controversy surrounding the Joseph Smith Translation?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So the most recent controversy surrounding the Joseph Smith Translation is what’s called the Adam Clark controversy, and I’ll put this in a nutshell for you really fast. A couple years ago, two individuals at BYU, Tom Wayment, who’s a professor of classics, and Haley Wilson-Lemmon, who was Dr․ Wayment’s research assistant, published some research that noted similarities between the changes Joseph Smith made to the Bible and a commentary published by a British scholar named Adam Clark.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, actually, the first time that this information appears is in a work called The Pearl of Great Price Reference Companion. It’s an excellent book. Get a copy—where Kent Jackson, who’s one of the eminent scholars of the Joseph Smith Translation, actually referenced this. Kent Jackson had apparently talked to Tom and Haley and basically heard their research that Joseph Smith may have been influenced by Adam Clark’s translation, and he makes an offhand reference to it. Now, at first, this really isn’t super earth-shaking at all. I mean, it might be a little surprising, but most of the Latter-day Saint scholarly community kind of went, “Oh. Hey. That’s kind of cool. It actually fits Joseph Smith’s modus operandi to say that he may have used a Bible commentary.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

You included this nice quote here, Scott, from the prophet. He said, “One of the grand fundamental principles of Mormonism is to receive truth, let it come from whence it may.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Joseph didn’t really care about the source. As long as it was true, he says, “We believe it.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So he was open to that kind of thing.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And like we said, most of Joseph Smith’s work on the Bible takes place from 1830 to 1833. And that’s early on in the prophet’s career.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But later on in Joseph Smith’s ministry, he shows a real desire to engage with scholarship on the Bible. He hires a Hebrew teacher named Joshua Seixas, who starts a Hebrew school. In Kirtland Joseph Smith expresses a desire to read the Bible in the original languages, Hebrew and Greek. In the King Follett sermon he references reading the Bible in German and really enjoying it there.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And it seems like he has no issue working with scholarship when it comes to the Bible, so on the one hand, this is great.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Honestly, when I first heard about this, I thought, “Oh, that’s cool.” And I started actually teaching it to some of my students when it would come up, especially in our Foundations of the Restoration course as we’re talking about Joseph Smith producing scripture.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And I thought it was a cool illustration of Joseph Smith being true to that idea of receiving truth from any source out there—that Joseph Smith was unafraid of scholarship or insights in other religious traditions, right? He would say stuff like, “Do the Baptists have any truth? Yeah. Do the Methodists have any truth? Yeah. They all have truth, and we’ll receive truth from anywhere.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So I thought, “Oh, cool. This is a cool example of Joseph Smith doing that. He’s finding truth in Adam Clark’s commentary, and he is incorporating it as sort of authorized by the Spirit.” I found no problem with that. My students didn’t find any problem with that. Everything was fine.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Everything was fine.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I mentioned it in my classes, too. I’d bring it up and say, “Hey, Joseph Smith may have even used a commentary to help with the translation.” Everybody was like, “Oh, OK.“ Like I said, it fits his way of doing things, so there really wasn’t much of a controversy to begin with when this research was first published.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. It even made it into the Church History Topics Gospel Library app. I had this quote here that I used in my class from that. I don’t even know if it’s still there. I should double check. But it says, “As he [Joseph] worked on these changes in the Bible, he appears, in many instances, to have consulted respected commentaries by biblical scholars, studying them out in his mind as part of the revelatory process.” That’s how it was phrased there. And this is all based on this work from Tom Wayment and Haley Wilson-Lemmon.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And so, as you said, Kent Jackson, he felt no problem talking about this.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And he put the very first printed assertion about this in that commentary for the Pearl of Great Price. And he said, “I made that statement without doing the research myself, but I trusted the scholarship of Professor Wayment.” But we were all kind of on board based on this scholarship. Tom’s a good scholar. He’s got a good reputation. We had no reason to not believe it, correct?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And, I mean, it fits everything we know. In the revelations Joseph Smith was given, he’s told to seek knowledge out of the best books even by study, also by faith, so saying that the JST was a combination of revelation and scholarship is something that actually fits. And in the early 19th century, there’s a lot of commentaries floating around, commentaries where authors would discuss the text, sometimes even offer alternate wording, which is something like Joseph Smith is doing. Just to list a couple, John Gill, James McKnight, Matthew Henry—I have Matthew Henry’s commentary on my shelf right now—Thomas Koch, and Adam Clark. Now Clark’s is probably the biggest.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, multi-volumes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And if you want to read Adam Clark’s commentary, you can find it on Kindle. I think it’s, like, 5,000 pages long in print, and it’s contemporary. Joseph Smith probably wouldn’t have had any trouble finding this, but he also never really claims to have used it either.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. There’s no record of him ever referencing it.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

In any talk or council meeting or anything.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So why is this controversial, Casey? Why is this controversial? Where did that come from?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So we’ve been kind of explaining that the best way to understand the JST is not to see it as a single thing, but as at least five different things. And Kent Jackson, when he addresses this, simplifies the list down to three things, okay? Three types of changes that Joseph Smith is making. He says, one: Blocks of entirely new texts without biblical counterpart. Best example of that: Book of Moses.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Joseph Smith— Matthew. Just huge additions to the text that aren’t in the Bible.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He says two: revisions of existing texts that change its function and meaning. A lot of the JST changes the meaning of the Bible, sometimes fixing doctrinal problems that exist. And three: revisions that changed the wording of the existing text, but not the meaning.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And like I said, another thing that made this not controversial was that most of the changes that Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon were tying to Adam Clark were category three. They were revisions that changed the wording of the existing text, but not the meaning. And so, again, it’s no reason to really kind of worry about it. So it turns into a controversy because when Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon published their final findings, they publish it in a chapter in a book. The title of the chapter is “A Recovered Resource: The Use of Adam Clark’s Bible Commentary in Joseph Smith’s Bible Translation.” It’s in a book published by the University of Utah called Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith’s Translation Projects. And after that, things get a little intense. And before we dive into this discussion, I want to preface that these are all living people.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And we’re not trying to smear anybody’s reputation.

Scott Woodward:

Sure.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s a lot easier to talk about dead people than living people because you’re not going to run into them, you know, at lunch. And so we’re not trying to make anybody look bad. We’re just trying to explain what happened here, and as we do this, we’re going to try and use words that come directly from the people so that we don’t misrepresent them.

Scott Woodward:

I remember this article being very built up.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

I mean, this starts way back in 2017.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And this article’s not published until 2020. And so they had some, like, interim articles and interviews that they did where they were kind of sort of summarizing some of their findings, and this was creating a buzz, right? Kind of interest and not yet controversial.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So, okay. So pick it up. So then it actually gets published in 2020.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And then what happens?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

After that, things started to get intense. So Hailey Wilson-Lemmon leaves the church, and she claims that her work on the project had a significant negative impact on her testimony.

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And she starts to appear on anti-Mormon podcasts, and in the podcasts they start to use the word plagiarism—

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—to describe the Joseph Smith Translation, saying that Joseph Smith stole from Adam Clark.

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now this sort of turns what was kind of an interesting scholarly development on the JST into an attack on the integrity of the JST.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Because they’re throwing around words like plagiarism—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—and calling into question Joseph Smith’s inspiration.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

As he works on the Bible translation.

Scott Woodward:

It’s almost an attack on his prophetic authority.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

As a prophet, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And I want to be clear: it’s Haley Wilson-Lemmon who’s making these assertions, not Tom Wayment.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

She kind of breaks with him and starts doing this.

Scott Woodward:

So she cites this as the reason for her leaving the church, correct?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

In some of her sources she says it’s a number of reasons.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It seems like in the podcasts initially when she does this, she cites this as the main reason, and then she kind of broadens it as she offers other explanations. The most recent statement I could find from her, she says issues over the Book of Mormon was the primary reason.

Scott Woodward:

Okay. Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Anyway, this causes Kent Jackson, who, again, is the preeminent scholar on the JST, to become concerned, and he starts to do an extensive review of Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon’s assertions, and then he publishes an article that appears in the Interpreter, which is a great source.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And I’ll just read his words. Okay, so this is what Kent Jackson says.

Scott Woodward:

We’ll link it in the notes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We’ll link it in the notes. Yeah. This is an online article you can read for free. Check it out.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Said, “Since then,” since the controversy, “I have studied closely the Wayment article and the Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon article and their proposed connections between Clark’s commentary and Joseph Smith. I’ve examined in detail every one of the JST passages they set forth as having been influenced by Clark, and I have examined what Clark wrote about those passages. I now believe that the conclusions they reached regarding those connections cannot be sustained. I do not believe that there is any Adam-Clark-JST connection at all, and I have seen no evidence that Joseph Smith ever used Clark’s commentary in his revision of the Bible.”

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“None of the passages that Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon has set forth as examples, in my opinion, can withstand careful scrutiny.”

Scott Woodward:

Shots fired. Woo.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So he comes out swinging. And here’s the thing is the article that he writes is long.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And he goes out of his way to go through every single example—

Scott Woodward:

Yes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—that Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon cite in their article as Adam Clark in the JST, and basically takes every single one of them apart.

Scott Woodward:

He handily dismantles them.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Handily dismantles every single one, point by point. In fact, I remember my experience reading Jackson’s article because, like I said, I had no problem with this theory or this latest scholarship finding that Joseph Smith had consulted Adam Clark and it influenced the JST. I was like, “That’s cool,” and I was teaching it in my classes. And then I read Kent Jackson’s article, and I did an absolute mental 180.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

As soon as I read this article, I just sat back in my chair, and I was like, “Oh my gosh. That whole theory is baloney,” right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Let me read Jackson on this: in the abstract at the very beginning, he says, “The evidence does not bear out their claim. I believe that none of the examples they provide can be traced to Clark’s commentary, and almost all of them can be explained easily by other means.” He says they misinterpret things. He says the few overlaps that do exist are vague, superficial, and coincidental, and then he goes to the article and just backs that up point after point after painful point.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And I thought it was interesting, too, that in 2017—so I have Tom in a short article called, “A Recently Recovered Source: Rethinking Joseph Smith’s Bible Translation.” This was on the 16th of March, 2017. So three years before the full article was published.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

But he said, “Our research has revealed that the number of direct parallels between Smith’s translation and Adam Clark’s Biblical commentary are simply too numerous and explicit to posit happenstance or coincidental overlap. The parallels between the two texts number into the hundreds,” he says. But then three years later, when the actual article is published, they only proposed thirty parallels.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So in Jackson’s article, he goes through every one of those thirty proposed parallels and dismantles them. Should we do a few examples, or is there anything else you want to say before we do that?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Let’s do a few, and we’re not going to go through all 30 because we don’t have six hours to do this, but we went through, and we picked out a couple.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And I mean, wow.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Hearing you read that makes me go, “Whoo. They may have jumped the gun a little bit on this.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So first example, we’ll start with the most famous JST footnote of them all.

Scott Woodward:

Dun, dun, dun.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Songs of Solomon are not inspired scripture. That’s the one that everybody references that all my students are aware of. When I got to see—and I got to see the JST manuscripts. The Community of Christ has them. I was photographing them for a book I was writing, and I went straight to that one. I was like, “Show me the Songs of Solomon.” Took a picture of that. That is one of the ones that Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon say came from Adam Clark. Now, what’s their reasoning for this?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I’m summarizing what Kent Jackson wrote, but their reasoning, basically, is that Clark, A, rejects the book as scripture, just like Joseph Smith does.

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And this wasn’t uncommon. A lot of people rejected the Song of Solomon as scripture during this time. However, their connection to the JST is that in the introduction of his commentary, Clark refers to the Song of Solomon by a traditional Latin title, that is Canticles.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Plural.

Scott Woodward:

Canticles.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Canticles, plural. And in the JST manuscript, Joseph Smith’s scribe, Frederick G․ Williams, writes “Songs of Solomon,” plural.

Scott Woodward:

Ooh. Is that the English interpretation of Canticles?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I guess so. But that is their connection. That’s why they say this is linked to Adam Clark.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, man.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Because Adam Clark refers to it as Canticles, plural, and in the JST, it’s not Song of Solomon, it’s Songs of Solomon. That’s pretty much it.

Scott Woodward:

Mm. You know, in Clark’s day, as well as in our own, some Christians like to read the Song of Solomon as, like, a allegory for Christ in the church, right? The church is Christ’s bride, and Christ is, like, writing these love letters to the church, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

Clark opposed that. In fact, let me read some Jackson right here. He said—I’m quoting directly from the article: “Clark opposed interpreting the Song of Solomon as an allegory for Christ and the church, as some Christians did. Indeed, he opposed interpreting it as anything other than what the words in it actually say, and he advised ministers not to preach from it.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And then here’s Jackson: he says, “With no more evidence than that, Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon come to the conclusion that Joseph Smith was influenced by Clark to reject the book as scripture.” And he talks about the Canticles and songs thing, but over and over again like this, he’ll just show, like, how thin the reasoning is for their supposed connections.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Let me read a little bit more from him. “He uses,” referring to Clark, “[Clark] uses the plural Canticles a total of three times in his introduction, but elsewhere he refers to the book over 90 times with singular titles, nouns, and pronouns. We may never know why Joseph Smith or his scribe chose “songs,” but nothing suggests that it was because of Adam Clark. Many readers, starting centuries ago, have concluded the Song of Solomon has not inspired writings, so the conclusions of Joseph Smith and Adam Clark were not unique to them. But there is something else to consider, not only here, but elsewhere as we look at the Adam Clark theory: By the time the prophet came to this book in his Bible revision, probably in the spring of 1833, he’d already dictated every word of the Book of Mormon and every word that would later be called the Book of Moses. He’d already received about 80 of the revelations now in the Doctrine and Covenants. I believe that he was in a unique position to discern the nature of inspired writings, and I don’t believe he needed suggestions from anybody else to do so.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So, I mean, that’s—whoa.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That’s pretty thin evidence that the JST footnote on the Song of Solomon is linked to Adam Clark. I mean, real thin.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Here’s another really thin one. Exodus 11:9. King James version says, “Pharaoh shall not hearken unto you.” Joseph Smith Translation: “Pharaoh will not hearken unto you.” Changing shall to will.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And for linguistic reasons, Jackson says, “Adam Clark criticized the King James translators for their use of shall here instead of will. So Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon suggest that Joseph Smith followed Clark in making this chain.” And then Jackson says, “But there’s no reason to think that this is the case. The manuscripts show that the prophet dictated both shall and will when revising texts. Prior to arriving at this verse, he had already changed shall to will in several places, including Genesis 23, Romans 3, Revelation 19. In a passage similar to the one here, he had already changed ‘He shall not let the people go’ to ‘He will not let the people go’ in Exodus 4:21. In a passage identical to this one, he had already changed ‘Pharaoh shall not hearken unto you’ to ‘Pharaoh will not hearken unto you’ in Exodus 7:4. Clark suggested none of those changes, and thus, because Joseph Smith made them prior to arriving at Exodus 11, the connection that Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon make with Clark is unfounded. The prophet made other significant changes in this verse and in surrounding verses, but Clark’s commentary cannot explain any of them. This is something we shall see repeatedly,” he said. There’s just this really thin evidence, and they’re making these really strong conclusions.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Sometimes they’ll say maybe or perhaps, to be fair, but other times they’re really strong. Like, let me quote another one from Tom. Back in 2017, he said, “This new evidence effectively forces a reconsideration of Smith’s translation projects, particularly his Bible project and how he used academic sources while simultaneously melding his own prophetic inspiration into the resulting text.” I mean, that sounds pretty grand. That sounds pretty, like, important, right? And then when you actually look at their examples, it’s things like from shall to will.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Which Joseph had already done and Clark doesn’t do in some places that Joseph does. And Kent Jackson, preeminent scholar on this, is scratching his head, saying, “Where is the profundity here? Why are we needing to force our reconsideration of Joseph’s translation projects based on this really thin evidence?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So do you want to do any other examples? Are we…

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Let’s do a couple more. So one that could be considered important: This is Matthew 5:22.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The King James text: “Whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause,” the JST changes to “whosoever is angry with his brother.“ Deletes the phrase “without a cause.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“Adam Clark’s commentary,” this is Kent Jackson, “points out that the Greek word translated ‘without a cause’ is not found in Vaticanus, nor in some other manuscripts, and it was probably a marginal gloss originally, which in process of time crept into the text.” So there’s a lot of manuscripts that don’t contain this phrase. He goes on to write, “This was not a revolutionary discovery because even the translations of Martin Luther and William Tyndale did not include the clause. Wilson-Lemmon states that the absence of this clause was the first discovery she made that linked Joseph Smith’s translation with the commentary of Adam Clark.” So Wilson-Lemmon actually says this was the first thing that she saw that caused her to connect it to Adam Clark.

Scott Woodward:

This got her going.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Right. But Kent Jackson goes on to say, “Clark was not the source for the prophet’s rendering of this verse. The Book of Mormon is.”

Scott Woodward:

Ah, shoot.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“The evidence is clear that when he revised Matthew 5, Joseph Smith edited the KJV text against 3 Nephi in the 1830 Book of Mormon, pages 479–81. He did not copy the Book of Mormon text exactly, but he inserted into Matthew 5 about thirty wordings of it that differ from the KJV. The Book of Mormon is the source of the absence of “without a cause” in the JST, not Adam Clark. In addition to those revisions, Joseph Smith’s translation of Matthew 5 also contains over ten other changes that cannot be accounted for with reference to Adam Clark.” So they’re basically picking one change out of ten in that particular chapter and using it as evidence that Adam Clark was the source when all ten line up with the Book of Mormon and the version of the Sermon on the Mount that’s found in the Book of Mormon.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So that’s a consistent thing is that they kind of say, “Ooh. This change lines up with Adam Clark,” and they don’t account for the dozens of other changes in the text around it or try to tie it back to Adam Clark. And again, Adam Clark isn’t the only person that’s putting this idea out there. It’s already in the Book of Mormon. Other biblical translators and scholars had pointed this out, and to tie it to Adam Clark is a little bit of a reach, to say the least.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. You know, Jackson says in part of his conclusion to all of this, I thought he worded it well here when he said, “The Adam-Clark-JST theory starts with the given that Joseph Smith borrowed ideas from Adam Clark, and then it searches through Clark for words that can be invoked as evidence for it.” Now, that’s kind of a backwards way to do scholarship, right? To start with your conclusion first and then go to try to find evidence for it.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

So this theory, this Adam-Clark-JST theory, did not seem to grow out of these astonishing connections into the theory. It started with a theory that then went backwards to look for connections, and maybe is we’ll just take Haley’s word for it, that it was that “without a cause” clause that was the first thing that cued her into, “Maybe there’s something here.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

But I agree that theory that started out so thin kind of became the lens by which they searched Clark, right? They’re looking for anything at all, anything that could be evidence. Little things, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And so, as Jackson says, “Indeed, if Joseph Smith borrowed from Adam Clark, the evidence would be obvious. There would be direct recognizable uses of distinctive words of Clark, and there would be a clear and repeated pattern of them.” And he says “the real explanations are almost always much easier and much more intuitive than the explanations that involve Adam Clark.” You just pointed out, like, the Book of Mormon, way before Joseph gets involved in the Bible translation project, he had already translated the Book of Mormon, and it doesn’t have that phrase.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And so, yeah, thick conclusions based on thin evidence.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I mean, that’s part of the challenge here, right? If they were just saying, “Hey, there’s a possible connection.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But some of the language that they were using, started out as “There’s a definite connection, and we can’t deny it.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. And we need to fundamentally reconsider Joseph’s translation projects.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. We need to reconsider everything because of this. And then that transforms later on into plagiarism. And you can’t make a charge like plagiarism without serious evidence.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Which they just don’t have. Let me go to the last argument Kent Jackson gives, which is the mathematical argument, okay?

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He says, “There is an insurmountable mathematical problem associated with the idea that Joseph Smith relied on Adam Clark.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“The prophet made changes in about 3,600 verses of the King James Bible.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“In addition to the thousands of words of new text he added that have no King James counterpart.”

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“In some of those verses, he made multiple word changes. Clark’s commentary provides hundreds of thousands of bits of data that the prophet could have drawn from in the JST, had he used it. The convergences that Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon propose are individually unconvincing, but they’re also tiny and random and statistically negligible compared with the massive amount of data available in Clark.”

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“On the other side of the equation, Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon cannot account for the thousands of changes Joseph Smith made that do not resemble in any way Adam Clark’s commentary.”

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“And they do not explain why Joseph would pay attention to one isolated comment from Clark in the midst of scores of others, nor why he would look to Clark to make revisions of little consequence while Clark was proposing many re-interpretations of significance. The numbers don’t work at all. The idea that Joseph Smith either read Clark’s commentary or has it in front of him or reads it at night, as Wayment maintains, cannot be sustained.”

Scott Woodward:

Whoo.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So what they’re suggesting is around thirty changes. I mean, I guess they suggested hundreds of changes.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, back in 2017. Yeah. 2017 was hundreds.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. They only actually cite 30 out of 3,600.

Scott Woodward:

And if those 30 are their very best examples.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

This theory is shot.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Using the word “plagiarism” is really off base here and totally unfair. And for the next part of our discussion, I want to show that at least Haley Wilson-Lemmon has backed off on calling it plagiarism.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, even after stepping away from the church, she’s…

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, even after stepping away from the church. So we wanted to basically allow each one of these three individuals, Haley Wilson-Lemmon and Tom Wayment and Kent Jackson to kind of speak for themselves.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And so in preparing the notes for the show, I tried to find where they had, you know, offered recent commentary on this. Haley Wilson-Lemmon went on to be a grad student. We noted she left the church. She hasn’t published anything since the chapter came out, but she did do an Ask Me Anything on Reddit.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Where people could basically ask any questions. So this is the way she introduced herself: “Hello, everyone. I’m Haley Wilson-Lemmon․ Wife․ Exmo․ Librarian․ … and I co-authored a little paper on the JST’ and Adam Clark. Ask me anything.” Now in the introduction to this, she also notes, “I will not discuss Tom or his personal beliefs about the project, the church, or anything adjacent to those topics. I appreciate your understanding.” And that’s kind of classy.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Let’s let Tom speak for himself.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. I’m not going to represent Tom or his beliefs. I’m representing myself.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

When she’s asked, “Are you going to continue to do this?” Someone asks, “What’s your next research project going to be?” She goes, “I’ve gotten this question a lot. I’m going to give a rather disappointing answer. I’m actually done with research for now.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“I’ve spent most of my life entrenched in Mormonism and in scholarship, and I’m looking to find my identity outside of Mormonism. I’m happy to talk research and help anyone who wants to try and maybe compare Clark to the Book of Mormon or something, but I don’t feel like I’m the one to do it right now.” So she’s not doing any research. Someone else asked about, “Hey, I think this research is important.” Someone said, “Hey, what do you think about this article that one of the editors of Producing Ancient Scripture,” the volume the chapter was published in, “wrote about it?” That is Mark Ashurst-McGee, who’s a member of the Joseph Smith Papers.

Scott Woodward:

Love Mark.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mark Ashurst-McGee basically comes out and says, “Yeah, I mean, it’s a small number of changes, and it doesn’t necessarily conflict with the idea that Joseph Smith may have used outside scholarship, and it’s not fair to call it plagiarism.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, referencing that, Wilson-Lemmon says, speaking to his idea, referring to Mark Ashurst-McGee, “We can’t call what Joseph Smith did plagiarism.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“Everyone will see it differently, and that’s fine.” So she actually says, “We can’t call it plagiarism.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Meaning she’s either walking back what she said or she was misrepresented on some of these podcasts.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

You can still go to the webpages of some of these podcasts, and they just outright say “It’s plagiarism. This is proof Joseph Smith plagiarized it.” But then she does make this point. She says, “The point is that Joseph Smith used Clark for his JST, and regardless of what you want to call it, that fact cannot be denied.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

She’s still sort of speaking of it as if it’s fact. When you look at the examples that they cited, I mean, it’s not settled scholarship at all.

Scott Woodward:

No. It’s debunked, I think, with Jackson’s article. It’s debunked scholarship.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

I want her to respond to Jackson, not Mark Ashurst-McGee. I want her to respond—like, has Haley or Tom responded to Kent Jackson’s article? Like, I haven’t seen anything that’s a direct response. Have you?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I couldn’t find anything. And this AMA came out after Jackson’s article. And she doesn’t address him. I mean, I read through the whole thing, and I couldn’t find any place where she addressed it. But to me the most important statement to say there was she actively says, “We can’t call what Joseph Smith did plagiarism.”

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So even she admits it doesn’t fit the definition of plagiarism that any responsible person would use.

Scott Woodward:

And that was the way that this research was weaponized originally, right? Was to say, “Uh-oh. Look at this scholarship. Uh-oh. Joseph Smith was doing some shenanigans with the Bible. Uh-oh. This is plagiarism. This calls into question his prophethood and his Bible project translation. We need to radically reconsider all of this,” right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm.

Scott Woodward:

That’s interesting. So now she’s backing away from that and saying, “That’s not really plagiarism.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, basically.

Scott Woodward:

And read that line again. What did she say? She said “it’s not plagiarism, but I think it’s” what?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So speaking to his idea—she’s referring to Mark Ashurst-McGee’s assessment of their scholarship.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“We can’t call what Joseph Smith did plagiarism.”

Scott Woodward:

Uh-huh.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“Everybody will see it different, and that’s what’s fine. The point is that Joseph used Clark for his JST, and regardless of what you want to call it, that fact cannot be denied.”

Scott Woodward:

And then you read Jackson, and it’s like, “That fact can totally be denied.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

That fact can absolutely be denied, that he used any Clark whatsoever.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, Haley.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Let’s move on to Tom Wayment again, because we’re not trying to smear anybody. We’re trying to use their own words here.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Tom Wayment has also pushed back against the claim of plagiarism.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Tom Wayment did a little Q-&-Answer for From the Desk, which is Kurt Manwaring’s blog. It’s excellent. Everybody should subscribe to From the Desk. I think it’s great.

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And Tom is kind of maintaining Joseph Smith did use Adam Clark. He’s still holding out on that, but here’s what he says: These are Tom’s own words. “The use of sources in completing new scriptural projects is not surprising, and biblical authors used other texts when they constructed their own texts without offering direct attribution. They quoted and adapted their sources for their own needs, and they were deeply influenced by their cultural setting and environment. Unfortunately, when this discussion arises with respect to the text of the Book of Mormon, the JST, and the Book of Abraham, the conversation partners often draw stark boundary lines of orthodoxy and heresy between those who seem to claim that all of Joseph Smith’s scriptural projects were completed without the influence of external sources and those who find Joseph’s scriptural projects as simply derivative from his cultural inheritance. Unfortunately, I think the conversation about the article and subsequent article I published on the topic in the Journal of Mormon History was quickly surpassed by the online conversation of the article.

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Words like “plagiarism” have been used to describe Joseph’s use of Adam Clark, and some outlets were willing to use that term even before the article appeared in print.

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“I think many people eagerly anticipated that the article would settle the issue of whether Joseph plagiarized the work of Adam Clark. When someone uses a term like plagiarism to describe Joseph’s use of Adam Clark, that person should be careful to note whether the definition is based on modern concepts of plagiarism or whether one is basing that acquisition on an 1830s definition of the concept. Joseph Smith consulted a Bible commentary by a noted Methodist theologian.” Again, he’s talking about this like it’s fact.

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“I believe there is little doubt of that. His use of that source shaped the way he translated verses. Today a person who consults a Bible commentary and then, as a result, alters the translation that a person is working on needs to footnote the source that was consulted. I don’t wish to obfuscate this reality, but I also want to avoid anachronistic descriptions of what happened.”

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So he’s trying to be fair, right?

Scott Woodward:

He’s trying to be fair. So he still believes that Joseph used Adam Clark.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But he doesn’t think he was doing anything sketchy.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Because that was according to the way you did things at the time. You didn’t have to footnote your sources—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

—in 1830.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And one of the valuable things he says here, too, is that these charges of plagiarism were being made before he even published his final article. And so this was a case where, you know, people that weren’t even involved in the scholarly debate, that weren’t even doing the scholarship, just took this hint of an idea and all of a sudden started using the word “plagiarism” to describe what Joseph Smith did. So I think it’s fair to say that Tom Wayment isn’t saying Joseph Smith plagiarized Adam Clark. He still believes Joseph used Adam Clark—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—in his translation, but he’s not making any assertions of plagiarism or anything that would really upset the apple cart about what we believe the JST is.

Scott Woodward:

Tom is a little more fair and circumspect than a lot of people are with Tom’s own scholarship.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And then one more thing that he writes, “If I am correct and Joseph used an academic source, even if it amounted to only a few hundred changes out of the nearly 1,200”—he’s using weird numbers here, too.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—“we can begin to think of a new paradigm for how prophetic speech or prophetic translation is done.” So he’s saying, “Hey, even if it only accounts for a few of the changes, it doesn’t discount Joseph Smith’s role as a prophet.” So I think he’s been a little unfairly misrepresented here, too.

Scott Woodward:

So he just said, “We can begin to think of a new paradigm for how prophetic speech or prophetic translation is done.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

I think, and Tom needs to speak for himself on this, because he’s still alive—it’s not like trying to get into the mind of a dead person—but I sense that’s what stake Tom has in this. He’s trying to promote maybe a new paradigm—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

—for prophetic speech or prophetic translation. He wants us to think more openly about scholarship and to be more okay with using scholarship or to see how prophets have used scholarship in the past.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

That seems to be the angle he’s coming at this, right? Just saying that, “Hey, we don’t need to be afraid of scholarship. Joseph Smith used scholarship. He even used it in his Bible translation project.” Although with Jackson’s articles, we don’t agree with that, but I think that’s the point. He’s not saying something really damning of Joseph. He’s just, I feel like, trying to shift the paradigm. Would you say that’s—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

How you read it?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I think that’s where Tom’s coming from, and Tom’s trying to basically say, “Hey, if Joseph Smith used a commentary, it doesn’t invalidate his role as a prophet. It doesn’t mean that the JST isn’t inspired.”

Scott Woodward:

Just means we need to rethink our assumptions about Bible translation. That’s all he’s saying. Right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So continuing on, Kent Jackson, after his article came out, has written things about this, too.

Scott Woodward:

Hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Here’s what Kent said: “In researching the JST and coming to believe that it includes influences from Adam Clark’s commentary, Professor Wayment was doing what scholars do: establishing a hypothesis, testing it, and drawing conclusions about it. It is obviously not uncommon for scholars to have different opinions as he and I do about this matter, but his views on this topic have been overshadowed by the fact that his co-author, Haley Wilson-Lemmon, has been claiming the research shows Joseph Smith plagiarized from Clark. Wayment hasn’t made this claim: she has.” And we noted she’s backed off on this, too. Then Kent Jackson goes on to say, “Even if their theory were true, it wouldn’t be plagiarism because the convergences they propose amount mostly to isolated words and vague resemblances. At best they could say Joseph Smith was occasionally influenced by the things Clark wrote, though I don’t believe it.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So he basically comes out and says, “Wayment isn’t claiming plagiarism.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“And even if he is, I don’t think that the evidence is there to prove that there was any kind of plagiarism that exists.”

Scott Woodward:

And then he said—he goes on in that. Can I read that next part?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, please.

Scott Woodward:

He said, “The charge of plagiarism comes from interviews Wilson-Lemmon has done with aggressive critics of the church.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

“Who have used her and put words into her mouth for their own purposes. She has willingly acquiesced. She famously left the church and has used the Adam Clark idea as a means of advertising her disaffection. This has made her a minor celebrity among anti-Mormons, and it has brought the Adam Clark notion into the mix as evidence that Joseph Smith was a fraud.” And then he says, “I find all of this to be intellectually dishonest, but this is the kind of thing that many critics of the church do.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. This is a great example of that old saying that a lie can make it halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to even put its pants on, right? Where basically everybody, even before they had published their article, was taking the one-sentence description and running off in a totally different direction with it and claiming that Joseph Smith plagiarized it. And, I mean, honestly, I’ve never had a student bring this up in class. I have a colleague who has had a student bring it up, but the way the student phrased it was, “Isn’t it true that Joseph Smith plagiarized all of his translation?”

Scott Woodward:

Wow. That’s where it’s grown to, huh?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. That’s not what Tom or Kent or even Haley Wilson-Lemmon was claiming to begin with.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But that’s the one-sentence distortion of how this research has turned out. And this episode, maybe as much as anything, kind of illustrates, hey, when a new idea comes along, it’s okay to get excited about it, but don’t embrace it until you’ve had a chance to fully explore it. It takes time for scholarship to be tested and measured, and before we radically restructure our view of something, especially Joseph Smith’s prophetic role, we need to take the time to sort of slow down.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And test the hypothesis and make sure it’s even a valid hypothesis to begin with.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. It almost reminds me of the Salamander Letter.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Back in the day.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

With Mark Hofmann and his forgery. And some people, that radically, like, shaded the way they viewed Joseph, even to the point of many of them thinking he was a fraud. Some people left the church over that. And then later it comes out that that was a forgery.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

That Mark Hofmann had made it look like Joseph had said something like Angel Moroni being, like, a white salamander or something like that. Something kind of odd and ridiculous.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And, you know, that’s an interesting case study of “Slow down. Let’s let the scholarship do its work. Let’s let all hypotheses be tested,” like you’re saying. Let’s put some critical thinking onto this.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Be careful. Think slow, not fast about these things. Be slow to conclude and quick to look into what bolsters those assumptions, what bolsters the assertions. What’s the evidence behind the claim?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

If you go about these kind of things slowly, usually you’re not rattled by them.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And it’s so typical of what some critics of the church do, where they make a claim, they try to get a person caught up in the emotion of that claim, and they ask the person to make an immediate action. “You’ve got to leave the church. This isn’t right.” That kind of thing.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Alert. Alert. Scandal. Scandal. Fraud. Fraud, right? Kind of just—kind of, yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“This is huge. Here’s the one sentence version of this.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

When you sit down and you start to explore the controversy and you realize, “Hey, I don’t know if there’s a controversy here to begin with.”

Scott Woodward:

This is a nothing burger.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Last, I want to look at how a scholar outside the controversy would look at it. So this is Mark Ashurst-McGee, who both of us know. Mark’s a great guy.

Scott Woodward:

I know of Mark. I admire Mark. We—I don’t think we’ve ever met, but I admire his work. I think he’s an incredible example of a humble scholar.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Bright and meek.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And I know Mark pretty well. He’s hung out in my office. We’ve talked. I still admire him.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So when this controversy kind of blew up, because the article was published in Mark’s book, and then all the podcasts, all the controversy happened after that. Mark is asked, “Hey, what do you think?” In fact, here’s the question that was asked for him. This is also in From the Desk: “Does Joseph Smith’s use of Adam Clark commentary lessen the importance of the Joseph Smith Translation?”

Scott Woodward:

Okay, hold on a second. There’s an assumption in that question that he did use it, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So this must be before Kent Jackson’s article.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This is before Kent Jackson’s article.

Scott Woodward:

Got it. Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So here’s what Mark says. Mark says, “No. It doesn’t. And let me explain why, though this will take a minute.” Again, you see this characteristic?

Scott Woodward:

Slow down.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Let’s slow down. Let’s don’t run off before we, you know, know what we’re actually talking about. He said, “Church historians have recognized for decades that there is a broad qualitative spectrum of content in the Joseph Smith Translation.” That’s what we’ve been arguing in this series the entire time: that the JST is way more complex than it usually gets presented as, and it’s better to consider that complexity.

Scott Woodward:

It’s not just one thing.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. He says, “At one end of the spectrum there are the substantial expansions regarding Moses and Enoch. It’s quite clear these are meant to be understood as the result of revelation or revelatory translation. At the other end of the spectrum, there are mundane word changes that update the language of the 17th century King James translation for a 19th century audience. Church historians have long been open to the idea that revelation was not required for these mundane changes.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“There’s a wide range of changes in between these two extremes, with a large gray area in the middle where it is unclear whether changes are meant to be understood as the result of revelation or reason.” And again, this all lines up with what the Lord tells Joseph Smith. Use the best books.

Scott Woodward:

Study it out in your—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Study it out in your mind. By learning and also by faith. This is all in the Doctrine and Covenants, right?

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He said, “It’s certainly possible that the entire Joseph Smith translation is inspired, at least in the sense that Smith was inspired to modernize some of the words in the Bible for Latter-day Saints of his time. But even in this scenario, is it the case that every single word change is meant to be understood as a result of pure revelation?”

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Then he walks through and points out a couple changes that Joseph Smith consistently makes. Like, we mentioned this, but he changed woteth to knoweth.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Wot to know and wist to knew.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He changed things like afore to before and aforehand to beforehand. He revised alway to always and amongst to among.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mark says, “Must we assume that Smith meant for this change from amongst to among to be understood as the result of revelation? This is just a small smattering of examples of such mundane revisions, over 1,200 by my count.” And I guess that’s where we harmonize what Tom was saying versus what Kent was saying. Kent’s saying there’s 3,600 changes total. Tom is saying of the category where the words were revised, but no significant doctrinal changes, there’s 1,200.

Scott Woodward:

That makes sense. Fair enough.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay, fair enough. Okay, so Mark goes on to say this: “While it is theoretically possible that Smith meant for every single one of these revisions to be received as revelation, it seems much or more likely to me that this was not his intent. And if this is the case, then Smith understood the Joseph Smith Translation to be the result of both revelation and reasoning in his own mind. Let’s think through that further. Joseph Smith didn’t live in an intellectual vacuum, even if Joseph was a very intelligent and creative person, it’s unreasonable to hold that the reasoning he employed in updating archaic words was confined to the interior of his brain.”

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“That it was hermetically sealed off from family, friends, and associates.” I mean, is it that outlandish that he could have turned to one of his scribes, say Sidney Rigdon or Oliver Cowdery, and said, “Should we change this word to this word because it’s a little bit clearer when we’re doing this?” That seems totally reasonable.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But again, I mean, there’s extreme ends on this part of the argument, but the conclusions that we basically come to are it’s not a big deal to begin with, even if it’s true.

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And Kent Jackson’s work really casts a lot of doubt on whether or not the Adam Clark theory is even true to begin with.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. I think it thoroughly dismantles it, but there might be some that still hold to that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

That’s fine. We could still be friends.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. We could still get along and everything like that, and I still, you know, respect Tom and think he’s a good person and don’t have any—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—personal attacks to make on him or his faith or anything like that.

Scott Woodward:

I actually like Tom a lot. I think that he’s a good soul.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I do, too, and I feel bad that he’s been misrepresented in this controversy. I hope that it hasn’t injured him or his career or anything like that.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Nevertheless, our highest obligation is to truth, right?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So let me try and put this all together, because we’re near the end of our episode.

Scott Woodward:

Bring it home for us.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

1. Thomas Wayment, the primary scholar involved in the Adam Clark controversy. Never claimed, never claimed, does not to this day claim joseph Smith plagiarizes work from Adam Clark. He just claimed that Joseph drew from Adam Clark as he was making these grammatical revisions.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Both Wayment and Kent Jackson have stated that they have no problem if this is true, and we want to be clear with that. Kent Jackson is saying, “Hey, if it’s true, it’s not really a big deal to me. I’m fine with it.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Haley Wilson-Lemmon, this is Tom’s research assistant, is more of a question because she appears to have claimed plagiarism when she appeared on some of these podcasts.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But in her Reddit AMA, which was the most recent statement I could find from her, she said that it wasn’t plagiarism. She said we can’t call it plagiarism.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But she holds to Joseph Smith used Adam Clark.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Point number 2. When Kent Jackson reviewed all of the examples provided by Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon of Joseph Smith possibly using Adam Clark as a source for the JST, he didn’t find any that could be explained away as anything other than coincidence.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Big, fat zero.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And I actually was in a meeting where Kent Jackson spoke about this.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We all came in with that theory of, “Hey, we’re totally fine with this if this is the case.” We asked Kent, “How many changes do you think are linked to Adam Clark?” and Kent just basically said, “Zero.” None.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I haven’t found any that can be definitively tied to Adam Clark, and I think if you read his article, he really kind of brings the receipts to that claim.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It becomes really tough, especially for some of the ones that are more important—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—to tie them to Adam Clark.

Scott Woodward:

Let me read one more quote from him in his conclusion. This is from Kent Jackson. He said, just to put a fine point on this:

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

“Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon cannot produce convincing corollaries between Clark’s words and the JST, and that convinces me that there are none. Instead, the selective choosing of vague, distant resemblances out of large blocks of Clark’s wordy text, in which nothing else resembles the JST, coupled with misinterpretation of Clark’s words and lack of analysis of JST revisions in context, produced a theory that does not hold up.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yep. Point number 3. Whether you agree with Kent Jackson or whether you agree with Tom Wayment or whether you agree with Haley Wilson-Lemmon, they all agree that the changes even cited as being linked to Joseph Smith are a very small number of changes in the JST. Mark Ashurst-McGee estimated that it was less than 5 percent of the total changes, and that’s real generous.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

None of the academic studies mentioned by us today really actually threatened the integrity of the Joseph Smith Translation.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So, I mean, in conclusion it’s like you said early, this is kind of a big nothing burger. I think critics of the church tried to turn it into the controversy of the week, as they’re wont to do.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But like most controversies that they stir up, when you really sit down and look at it, it’s not a controversy to begin with. They’re misrepresenting the people that they claim have brought this to light, and they’re really just trying to score points for whoever they serve as a way of, you know, attacking the integrity of Joseph Smith, the Restoration and his witness of Jesus Christ.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So that was an hour to basically reach the conclusion that this is nothing, but…

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. What we’ve tried to do today is highlight the importance of good scholarship.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Right.

Scott Woodward:

I mean, thank God for someone like Kent Jackson who is both able and willing to slog through the weeds, verse by verse, go to Clark’s commentary, and there’s actually multiple versions of Clark’s commentary that he cites and he goes through.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So thank you, Kent, for slogging through all of that to be able to show us what it looks like to challenge assumptions, question conclusions, and really go to the evidence, go to the original sources on all of this, the original manuscripts of the JST, the original Adam Clark stuff, see everything in context, compare, contrast, and come to more informed conclusions. I think what he has done is just a fantastic example of what faithful scholarship looks like.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

It’s not starting with the conclusion and then just finding evidence for that, right? It’s let’s look at all the evidence together.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And I mean, maybe our listeners aren’t that enamored with knowing how the sausage gets made as you and I are, Scott, but this is a classic case study of how scholarship works.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

A scholar makes an assertion, another scholar is allowed to question that assertion.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They present their evidence back and forth. So far, Tom Wayment hasn’t really given a response to Kent Jackson’s assertions that I can find, but Tom Wayment could publish an article tomorrow saying, “No. You’re wrong. Here’s the reasons why.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And in all cases, scholarship has to be rooted in responsible academic methodology, or it can lead to wrong conclusions that could impair or hurt someone’s faith.

Scott Woodward:

That’s right. Well summarized. So thank you all for hanging with us through all of that. Hopefully you got some nugget out of that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Hopefully. I want to say I had a blast going through all this research. I mean, I just, like, haven’t thought about anything else for the last couple of days, and this was sort of exhilarating. It was like reading a novel with a lot of great twists along the way.