Revelations and Translations |

Episode 6

How Has Canonizing/De-Canonizing Happened in the Doctrine & Covenants?

62 min

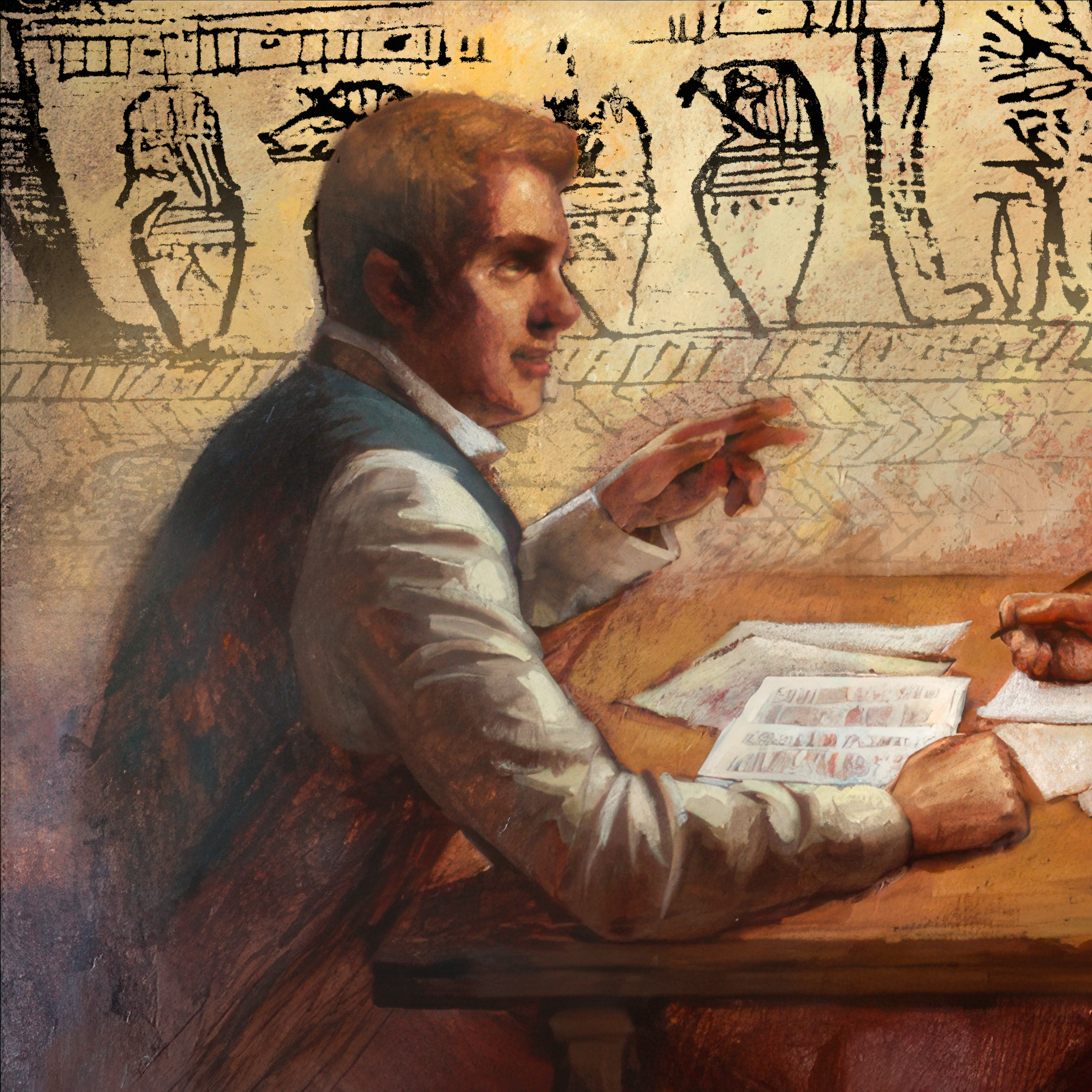

Because of our location in time and good record keeping, we are privileged to have an up close and personal view of the production of modern scriptural canon, and as we get into it, it’s a bit of a rollercoaster. From its first publication in 1835 to its current version today, the Doctrine and Covenants has undergone major additions, deletions, rearrangements, and textual changes. In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we’ll take a ride through the history of this iterative production of the Doctrine and Covenants, from its earliest 1833 version, known as the Book of Commandments, to its 1835 version, which added new revelations and seven major theological lectures known as the Lectures on Faith, to the 1844 version, which added a few crucial revelations and was the last version most of the branches of the Restoration agreed upon after Joseph’s death, to the 1876 version, which contained massive additions and rearranging, to the 1921 version, which decanonized the Lectures on Faith, and finally to the version we use today, which underwent revisions as recently as 2013.

Revelations and Translations |

- Show Notes

- Transcript

Key Takeaways

- The Doctrine and Covenants has not always existed in its current form: It has undergone a number of changes through its history, both additions and subtractions. In other words, it has been subject to both canonization and decanonization.

- Most of what we know about “original” versions of the revelations we know because of manuscript revelation books, often recorded by John Whitmer. The earliest versions of revelations are usually from these books, and they can be found at the Joseph Smith Papers website.

- The first version of the Book of Commandments was only partially published. A mob attacked and destroyed the press and many copies of the pages that had already been printed, but several incomplete copies were saved by two brave young women, Mary and Caroline Rollins, and a man named John Taylor (not the same Taylor who would eventually become prophet).

- The Book of Commandments is so named because the term “commandments” is used synonymously with the modern term “revelations” in the book.

- In 1835, a new version of the Book of Commandments was published in Kirtland, Ohio, with additional revelations. This version was named the Doctrine and Covenants, with “doctrine” referring to the Lectures on Faith and “covenants” referring to the revelations themselves.

- The Doctrine and Covenants underwent further revisions in 1844, including the addition of a section commemorating the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. This version became the final standard work accepted by various Restoration movements.

- The most significant revision of the Doctrine and Covenants occurred in 1876, overseen by Orson Pratt. It reorganized the sections chronologically and added 26 new sections, including key ones related to priesthood and temple ordinances, in response to challenges of authority from the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (now Community of Christ). 1876 also saw the removal of an article on marriage and the addition of Section 132, which dealt with eternal and plural marriage. This marked the first example of decanonization.

- In 1921, a scripture committee oversaw a new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, which included the removal of the Lectures on Faith, a significant act of decanonization. The committee felt these lectures contained questionable or unclear doctrine.

- In 1981, another edition of the Doctrine and Covenants was published, adding Sections 137 and 138, which were originally found in the Pearl of Great Price. Section 138, in particular, contained new revelations about the postmortal spirit world.

- In the 2013 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, 75 sections were changed, but most of the changes were in the historical introductions before each section, not the text of the revelations themselves. The changes to the text were minor, such as correcting spelling or punctuation errors, and they resulted from meticulous historical research conducted by the Joseph Smith Papers Project.

- The Doctrine and Covenants is a living and dynamic scripture, and changes reflect the ongoing process of understanding and refining its content. Members should embrace this dynamism and recognize that scripture is continually created to meet the needs of the Church and its members.

- The Doctrine and Covenants serves as a testament to the ongoing revelation and canonization processes within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and it is still in the process of creation. Perhaps additional sections will be added in years to come.

Related Resources

Steven C. Harper, “‘That They Might Come to Understanding’: Revelation as Process,” You Shall Have My Word: Exploring the Text of the Doctrine and Covenants, Eds. Scott C. Esplin, Richard O. Cowan, and Rachel Cope, 2012.

Scott Woodward:

Because of our location in time and good record keeping, we are privileged to have an up close and personal view of the production of modern scriptural canon, and as we get into it, it’s a bit of a rollercoaster. From its first publication in 1835 to its current version today, the Doctrine and Covenants has undergone major additions, deletions, rearrangements, and textual changes. In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we’ll take a ride through the history of this iterative production of the Doctrine and Covenants, from its earliest 1833 version, known as the Book of Commandments, to its 1835 version, which added new revelations and seven major theological lectures known as the Lectures on Faith, to the 1844 version, which added a few crucial revelations and was the last version most of the branches of the Restoration agreed upon after Joseph’s death, to the 1876 version, which contained massive additions and rearranging, to the 1921 version, which decanonized the Lectures on Faith, and finally to the version we use today, which underwent revisions as recently as 2013. So please keep your arms and legs inside at all times as we now embark on our tour of the ongoing story of the Doctrine and Covenants. I’m Scott Woodward, and my co-host is Casey Griffiths. And today we dive into our sixth episode in this series dealing with Joseph Smith’s non-Book-of-Mormon translations and revelations. Now let’s get into it. Hello, Casey Griffiths.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Hello, Scott. How you doing?

Scott Woodward:

Great. How you doing, man?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I’m great. Just raring, ready to go to talk about the Doctrine and Covenants once again, so.

Scott Woodward:

You seem like a guy who’s always ready to talk about the Doctrine and Covenants, Casey.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I love the Doctrine and Covenants. It’s my favorite. I mean, I love all the scriptures, but you know.

Scott Woodward:

I think you kind of let it slip there real quick. I think, I think you Freudian showed us that you prefer the Doctrine and Covenants. That’s cool. You know, respect. No judgment. Respect.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I teach the Doctrine and Covenants, so I am a little partial towards them.

Scott Woodward:

Totally. Totally. Well, we’re excited. This is our second episode on our discussion about the Doctrine and Covenants as part of a broader series about revelations and translations that are other than the Book of Mormon, and you pointed out really well last episode that these are all interconnected. We’re kind of going through them sequentially, but that’s not the reality of how they came about. It was Book of Mormon, and as the Book of Mormon’s coming about, there are questions that are being asked, and we get some of the early revelations of the Doctrine and Covenants during that time period. We then also talked about the Joseph Smith Translation, and that was huge in terms of influence on the Doctrine and Covenants, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

About half of the Doctrine and Covenants is revealed during the time that Joseph is working on the Joseph Smith Translation, and not by coincidence: It’s actually direct cause and effect. The Bible is inspiring him to ask questions, the answers to which become revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants. And so this is all kind of happening right on top of each other.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But as we pointed out last episode, the Doctrine and Covenants is not yet done. It’s still what we call an open canon. And so let’s talk about that. First of all, let’s review what, Casey, is the difference between scripture and canon? What do we mean by that?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay. This is a big part of our model, is scripture versus canon, and what the relationship between the two is, and I think the major question we’re dealing with today is, how does canon develop?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We use the definition of scripture that the Lord himself gives in section 68 of the Doctrine and Covenants, which I will again read here. The Lord is speaking to several individuals who later become apostles, but aren’t at this point, and He says, “Whatsoever they shall speak when moved upon by the Holy Ghost shall be scripture, shall be the will of the Lord, shall be the mind of the Lord, shall be the word of the Lord, shall be the voice of the Lord and the power of God unto salvation.” Now, that is a broad definition, but basically anything spoken by the power of the Holy Ghost is scripture.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. And you can hear that in sacrament meeting. Like, people can share scripture that are 10 years old. Like, they can speak and testify with what Nephi calls the tongue of angels, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But that’s not the same thing as canon.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

A woman gets up in your ward and shares a story about how she overcame her cancer. That’s scripture, if it’s done by the power of the Holy Ghost, according to the Savior’s own definition. But that definition is so broad, it can cause us problems because we can’t accept everything as scripture that people claim to. What if a person’s lying? What if they misunderstood and they weren’t actually speaking by the power of the Holy Ghost?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So in order to have some control, we introduced a second term, which is canon. And the definition we use for canon is a rod for testing straightness. That’s literally what the word canon means. It’s Greek.

Scott Woodward:

A rod for testing straightness.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

A rod for testing straightness. The Bible dictionary says it’s now used to denote the authoritative collection of the sacred books used by the true believers in Christ. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the canonical books are called the standard works. So scripture is this huge, huge category that could encompass everything from something that Moses said to something that, like you mentioned, a 10 year old says when they’re bearing their testimony. But canon is stuff that we know is scripture and we use as a measuring rod to figure out what is or isn’t scripture.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, as Elder McConkie, he says it like this: he says, “The standard works are the standard of judgment and the measuring rod,” he uses that phrase, “against which all doctrines and views are weighed.” And then he says, “And it does not make one particle of difference whose views are involved. The standard works always take precedence.” They always take precedence. And so he says wise people anchor their doctrine on the standard works rather than, like, quotations from individuals, even if those quotations, he says, are from apostles or quoted in General Conference. Like, if you really want to be solid, then you’re going to anchor your doctrine in what’s canonized in the standard works because that’s where it’s official and, as President Hugh B. Brown said, it’s binding once it’s in there. But you introduced a nice phrase I liked last episode. You said the harmonized canon. What does that mean?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So even going further than saying we use the scriptural canon, I would say we use the harmonized scriptural canon.

Scott Woodward:

Meaning?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And all that means basically is even if you can find it in the scripture canon. . .

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

If you can only find it in one place—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—we’re not saying it’s wrong. We’re saying be cautious with it.

Scott Woodward:

Be cautious.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Lord repeats ideas over and over and over again. And you should be able to find several data points in the scriptures where the same principle’s taught rather than just relying on one point. If I have a person come to me and say, “Hey, this scripture says this,” and it doesn’t say anything like that anywhere else in the scriptures, I’m not saying it’s wrong: I’m saying be cautious.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Scriptures can be easily misunderstood. They can be misinterpreted. And we don’t think the scriptures are perfect. They can be wrong. There can be errors in the way they were transcribed or misunderstandings, or sometimes we take a prophet sharing their opinion as revelation.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I think it’s 1 Corinthians 7:14 where Paul basically says, concerning this subject, I have no revelation, but here’s what I think. Here’s my judgment.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So it’s better for us to find it in multiple places in the scriptures than to just use one point. So we would say the harmonized scriptural canon is what we would use as the standard for truth.

Scott Woodward:

I love that. And once that clicked in my mind, that idea, I started finding apostles and prophets teaching that point over and over again. Like here’s one from Harold B. Lee: He said, “With respect to doctrines and meaning of scripture, let me give you safe counsel. It is usually not well to use a single passage of scripture in proof of a point of doctrine. To single out a passage of scripture to prove a point is always a hazardous thing,” he calls it. It’s a hazardous idea. And so every verse, President Boyd K. Packer said, “whether oft quoted or obscure,” must be measured against other verses to bring what he calls a balanced knowledge of truth. And maybe in a different series we should go into a bunch of examples of that. But for today’s purposes, that’s probably sufficient, though. Canon is different than scripture. It’s more official. It’s more binding. It’s more useful to try to get to a clear and confident measure of what’s true—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

—but even canon itself needs another level of internal harmonization, right? The harmonized canon. I love that concept.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And let me say another point that just comes to mind while we’re talking here.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Revelation and the harmonized canon are the two things we use to guide us, and one shouldn’t take precedent over the other. For instance, you’ve heard of John Krakauer’s book Under the Banner of Heaven.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It was even turned into, like, a TV miniseries and things like that.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And to get ready for the TV miniseries, because I thought my students would have a lot of questions, which they had no questions. I don’t know if very many people watched it, but. . .

Scott Woodward:

Nobody cares.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. John Krakauer’s big argument in his book is, in a church where anybody can get revelation, that’s crazy. Like, how do you know that a person’s revelation comes from God? Under the Banner of Heaven is about a group of people who left the church and claimed that they did so because God told them to, and then they committed a series of murders, some of which were really gruesome, because God told them to. Well, what Krakauer is missing is that Latter-day Saints believe that revelation is always measured against scriptural canon.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So if you’re thinking God told you to kill your wife, which is what the Laffertys said God told them to do—

Scott Woodward:

Oh my goodness.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—that’s clearly in contradiction to the scriptural canon, right?

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And he’s missing half the equation of how Latter-day Saints discern God’s will, which is one part revelation and one part measuring it against the harmonized canon to see if it’s right.

Scott Woodward:

I think he was missing a lot more than that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He, well, yeah, I mean, the whole book’s a mess, to be honest with you, and maybe we ought to spend an episode going through everything that’s wrong, because it is astounding how much he gets wrong in his book. But I digress. I just want to add what you said with Harold B. Lee to another prophet. This is Joseph Fielding Smith. He said, “My words and the teachings of any other member of the Church, high or low, if they do not square with the revelations, we do not accept them. Let us have this matter clear. We have accepted the four standard works as the measuring yardsticks or balances by which we measure every man’s doctrine.”

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So just another person saying, basically, yeah, we use the standard works as the yardstick.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This is how we know if scripture is scripture, if it actually is inspired by the Holy Ghost. If it doesn’t match the harmonized canon, then it’s really not something that came from God.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, and this is a very important safeguard, right? Because the reality is that even apostles and prophets, as Doctrine and Covenants 1 says, are weak and simple servants, right? Now, there’s some very impressive apostles, in my opinion, but the Lord calls them all weak and simple, and he says that they are error prone, and even sometimes sinful, right there in D&C 1. And so the underlying assumption is that humans are human and we make errors. Even humans that are called by God to be His servants are going to make errors. And so we need some standard by which to measure correctness and truth, and that’s what we call the canon, or the harmonized canon, as we’re talking about it.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

I want to just segue into today’s discussion by quoting from Steve Harper. We mentioned him in our last episode. Great article called “That They Might Come to Understanding: Revelation as Process,” and we’ll link to that again in our show notes for this episode as we did in our last. He said, “Prophets will continue to guide us as we continue to receive revelation actively in an ongoing quest for light and knowledge. They may amend the scriptures by the Holy Spirit as Joseph Smith did, when they discern ways to communicate with today’s global congregation more clearly. The prophets have made changes to the scriptures throughout history, including in this dispensation. The recent publication of a critical edition of Joseph Smith’s new translation of the Bible shows that he made thousands of changes to the biblical text as well.” And we talked about that in the Joseph Smith Translation episodes of this series. “We can choose to recoil in ignorance and disbelief from such facts,” Steve says, “or we can rejoice that we live in a time of wonderful discovery of our scriptural texts.” And then he says, “Perhaps we can learn from history about how to approach this moment of enlightenment. European scholars in the early modern period,” which is, like, 1500 to 1800, “began to study the Bible critically, using historical, textual, and linguistic analyses to assess the composition of biblical texts. They discovered that the oldest source materials for the Bible show the influence of several writers of what we casually call the Books of Moses, all written from different periods and perspectives.” This is what’s called the Documentary Hypothesis in biblical scholars. It’s really interesting.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yes.

Scott Woodward:

He then continues, “It became obvious that the biblical text had been revised and redacted again and again. As evidence and arguments mounted that biblical texts had been composed in a more complicated process than many believers had assumed, some concluded that mortal influence on scripture making precluded the possibility that the Bible was divinely inspired.” Ooh, if humans have had their fingerprints all over the text, then we cannot accept it as inspired. He says, “Other people retrenched the other way behind fundamentalism, the idea set forth by a group of American Protestants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the Bible is inerrant.” So they go to the other extreme saying, no, it’s not under question as to its inspiration. It’s actually flawless. It is flawless. No errors. He then concludes, “These two camps created a false dilemma, unnecessarily concluding that the scriptures must be either divine or human texts.” And that’s a dichotomy that we’re trying to break.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Like, there’s just human involved with the divine together in scripture—that scripture is a collaboration between humans and God, and whenever humans are involved, you’re going to find error. We ought to expect it. This should be baked into our assumptions about scripture.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And as we do so, I’ve found that that helps all of this actually land a lot more gently, and we approach scripture with a more nuanced sense of both faith and reason. We’re able to see God working with flawed humans, both in scripture and in the production of scripture. And as President Packer said, when you see that process up close, that actually strengthens faith. You’re watching what God does and how He works with humans. And ultimately, that’s actually pretty inspirational.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. I agree that, you know, we take these assumptions from childhood that, you know, the scriptures come directly from God, and as we transition into adulthood, we have to have a more nuanced and more complex understanding of how it works. And I’m 100 percent in agreement that understanding the process doesn’t hurt your faith. It helps your faith. It helps you understand the beauty and power of how God can work through a number of different people and make a difference in their lives through this process of creation.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And in the last episode we spent a long time talking about canonization, how something goes from being scripture to being part of the scriptural canon.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

In this episode we’re going to introduce another term, which is decanonization.

Scott Woodward:

Ah, shoot.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That’s how something goes from being part of the scriptural canon to being back to being scripture. It’s still good, but it’s not part of the measuring rod. The reason why the Doctrine and Covenants is so valuable is, like we said, it’s scripture in formation. We’re seeing a book of scripture be created before our eyes, and it’s being done under the direction of prophets and apostles, and every generation or so they do go back and review it and basically make changes to it. So I thought what we’d do today is go through the different editions of the Doctrine and Covenants and just kind of show you how the changes to the Doctrine and Covenants over time have been an illustration of how things become canonized. How could they go from being scripture to being part of the scriptural canon? And, at the same time, how things can sometimes be decanonized, go from being part of the canon back to being scripture for a number of different reasons, none of which are particularly sinister or anything of that nature.

Scott Woodward:

So our burning question of the day is, how is the canonization and decanonization process illustrated in the development of the Doctrine and Covenants? Is that about right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That is right. Well put. Let’s just walk through the different editions of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So let’s start with the most basic. It was very, very rare that Joseph Smith would go off by himself and come back with a revelation.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

In fact, it almost never happened because he always had a scribe. He would not write the revelations himself: He would dictate the revelations, and another person would write it down. And so the first thing is, what happens to these papers that the scribe initially wrote them on? Almost none of those original papers exist.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

There are a couple rare examples. For instance, section 100 of the Doctrine and Covenants. This is a revelation Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon receive in Perrysburg, New York. We think the original paper that they wrote the revelation on is at the Harold B. Lee Library in Utah. And I’m not saying it’s cryptic. You can go over and look at it. They display it all the time. But most of the time what would happen was is these original papers would be taken and copied into a manuscript revelation book by John Whitmer. And I’m giving a plug for John Whitmer here because I’m a member of the John Whitmer Historical Association, and a couple years ago we interviewed all the founders of the JWHA, and most of them made the joke that John Whitmer was a really lousy historian. Well, if you go by writing history, John Whitmer was a lousy historian. He only produces one history.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It never really gets published, and the history itself is not good.

Scott Woodward:

Joseph Smith said as much.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, Joseph Smith said—poor John Whitmer, like, Joseph Smith writes him and says, can you give us your history? I know it’s not very good, but we should at least have a copy.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

By that standard, he is a bad historian, but if you’re taking him as the church recorder, which is another important part of being a historian, not writing history, but recording things, he’s awesome. John Whitmer is great. So maybe he was a bad historian because he was so busy copying the revelations, which he does into these manuscript revelation books.

Scott Woodward:

There you go.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So you can actually, if you go to the Joseph Smith Papers site—and let’s take D&C 20: crucial, key revelation.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They have two examples there of two early members of the church, Algernon Sidney Gilbert and Harry Brown, who both copied Section 20 on their own. Then you have the manuscript revelation books, where John Whitmer took the revelation and copied it into the book so that they would all be in one place, so that when they decide to create a new book of scripture, the Book of Commandments, the Doctrine and Covenants, it’s all there. So thanks to John Whitmer, and as a recorder, top notch. He’s great.

Scott Woodward:

Good job, John.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

These manuscript revelation books were among the earliest editions of the Joseph Smith Papers published. You can actually get a facsimile edition that’s, like, a page-by-page photograph manuscript revelation book.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And in most cases, that’s the earliest version of the revelations that are available to us.

Scott Woodward:

Okay. Let me just summarize what you’re saying here. So whoever Joseph’s scribe was would write down the revelations that Joseph Smith dictated, but we have very few of those original, like whatever they were writing on, like that didn’t make it to modern day, with a few exceptions.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But John Whitmer took all of those originals, and he wrote them down, copied them, recorded them into a manuscript revelation book, and that is what we have mostly to go off of in terms of “originals.” Is that correct?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. In most cases, that’s the earliest version of the revelations that are received.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Again, there’s a couple exceptions like section 100.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

If you go to the Joseph Smith Papers and look up a revelation, they usually have the earliest copy there, and most of the time it’s the manuscript revelation book.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Another exception would be section 20, which actually appeared in a newspaper before it was found anywhere else, so that’s the earliest copy, and it’s in this newspaper that’s there.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But John Whitmer is commanded to take these manuscript revelation books—they hold a conference in November of 1831, and they’re literally dealing with the question of should we create a new book of scripture? According to the participants in the conference, most people were in favor. There were a couple of people that weren’t. The most prominent one is David Whitmer. David Whitmer, one of the witnesses of the Book of Mormon, actually says, I think these revelations aren’t intended for the world. Joseph Smith asks the Lord and gets a revelation that’s now section one that says these are intended for the world.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And they make the decision to go ahead and publish it. But originally it’s not going to be called the Doctrine and Covenants. It’s going to be called the Book of Commandments.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They decide to publish the Book of Commandments in Missouri because that’s where they’re going to build the city of Zion, and they’re setting up their printing operation there. So John Whitmer and Oliver Cowdery are instructed to take the manuscript revelation books to Missouri, and there put together the Book of Commandments. And they’re working on the Book of Commandments, and we run into problems. In fact, Scott, if I were to ask you what is the most, when it comes to monetary value, valuable artifact from early Latter-day Saint history besides the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon, what would you guess is the most expensive?

Scott Woodward:

I would say an original copy of the Book of Commandments.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That is correct.

Scott Woodward:

Yes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They are very, very rare. The last one that sold sold on the open market for 1. 7 million dollars.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, my word.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

If you can get one of these, good job. If you find one at your local Goodwill or Deseret Industries—

Scott Woodward:

Snag it.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—take it home, and put it in a box, because it’s going to be worth a couple things.

Scott Woodward:

Isn’t that so funny? Because what’s that original quote when Joseph asked that council in Hiram, Ohio, right—they’re at the Johnson farm, having that conference about publishing this text, and he asks the brethren what value they would put on the revelations that have been received, right? And then he—doesn’t he say, I’m trying to get his exact quote here, that “these revelations are worth the riches of the whole earth”?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. The conference voted that the revelations were “worth to the church the riches of the whole earth.”

Scott Woodward:

One-point—what was it? 1.7 million?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. They’re worth at least $1.7 million at this point now.

Scott Woodward:

So there are some rare book people who would pay one-point lots of million dollars.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So they’re not quite caught up yet to Joseph Smith’s estimation of the value of the revelations, but we’re getting there. We are getting there.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So why is a Book of Commandments worth so much? It’s because they’re really rare.

Scott Woodward:

So rare.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And why are they really rare? Well, originally they voted to publish several thousand copies of the Book of Commandments, but—this is probably a well known story: the printing press that they’re working with in Missouri is attacked by a mob in July of 1833. The mob destroys the printing press and destroys most of the copies of the Revelation that were being printed there. In fact, if it hadn’t been for a couple heroic early members of the church—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—who ran in and saved some of the revelations, we might not have any copies of the Book of Commandments at all.

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The two most well known ones are Mary and Caroline Rollins. Mary said that her and her sister ran into the print shop while it was being destroyed, they grabbed a couple copies of the revelations, and then they ran into a cornfield and laid down on top of the revelations while the mob was looking for them.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

She says that Oliver Cowdery took some of these copies that she had saved and bound them, and she got her own copy of the Book of Commandments because she saved it. They weren’t the only ones, either. There were other members of the church, too, like a guy named John Taylor. This is not the John Taylor.

Scott Woodward:

Different John Taylor.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This is a different John Taylor—he’s a 20-year-old convert of seven months from Kentucky. He said, “I asked Bishop Partridge if I might go out and get some copies of the Book of Commandments. He said it would most likely cost me my life if I attempted it. I told him I did not mind hazarding my life to secure some copies of the commandments. He then said I might go.” So he sneaks up to the print shop, he grabs as many copies as he can, and then he runs out. In fact, he says, “A dozen men surrounded me and commenced throwing stones at me, and I shouted, ‘Oh, my God, must I be stoned to death like Stephen for the sake of the word of the Lord?’ The Lord gave me strength and skill to elude them and make my escape without being hit by a stone.” And he ends his account by saying, “I delivered the copies to Bishop Partridge, who said I had done a good work and my escape was a miracle. These, I believe, are the only copies of that edition of the Book of Commandments preserved from destruction.”

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So he’s wrong, Mary and Caroline Rollins saved some copies, too, but because of that, there’s very, very few that are even able to be bound.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And if you can find one, like I said, hang on to it because it’s worth a lot of money. I’ve seen one. I was working on a book on objects. Can I mention my book here?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

50 Relics of the Restoration.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Community of Christ has a copy of the Book of Commandments that has Joseph Smith’s signature in it, and I was alone with it, photographing it for a couple hours. I could have just slipped it in my pocket and got out of there, but where would I have sold it?

Scott Woodward:

It’s because you’re a good person, Casey. You wouldn’t do a thing like that. You’re a good person.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I don’t know. I’m also afraid of punishment. But if you had a copy of the Book of Commandments, and you can buy facsimile copies, they’re not tough to find, you’ll notice that it actually ends in mid-section. So they were printing and they had made it to what is today section 64, verse 36, and that’s where the Book of Commandments ends. In fact, the Book of Commandments that they have on the Joseph Smith Papers site is Wilford Woodruff’s Book of Commandments, and you can actually see where he took the next page, which was blank, and continued writing the text. So it’s an incomplete work. It’s kind of a failure to launch for the revelations.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, so part one is Book of Commandments. And this confused me forever, but the reason it’s called Book of Commandments is because the word commandments was their word for revelations. Like, I didn’t get that for so long. I was like, “Why is it called the Book of Commandments? Are you supposed to be looking for commandments in there?” But each individual revelation was considered a “commandment,” and so—like, in D&C 1 where the Lord will say, I spoke to Joseph Smith, verse 17, and “gave him commandments. [I] also gave commandments to others.” Verse 37, famous scripture, “search these commandments, for they are true and faithful.” Like, the way that the Lord’s using that word is equivalent with, synonymous with, revelations. So Book of Commandments, Book of Revelations, to-may-to, to-mah-to, or as we say in Idaho, tomato potato, so. . . Okay, so what comes after Book of Commandments? So that’s destroyed. Most copies are destroyed. That’s 1833. What happens next?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Most copies are destroyed, and the printing press is destroyed, so they regroup. In 1835, two years later, they decide to publish an updated and improved version of the Book of Commandments. They’ve received several more revelations since then.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And they also want to go back and kind of more carefully go through them. So this happens in Kirtland, Ohio, which is a little bit safer at the time, and they publish a collection of revelations that for the first time is called the Doctrine and Covenants.

Scott Woodward:

Whoa.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, the actual origin of the name reflects kind of the structure of the book itself, too. The Doctrine and Covenants has all the commandments given in the Book of Commandments and more, but also includes the Lectures on Faith—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—which are a series of theological lectures given in Kirtland. In fact, if you look at an 1835 Doctrine and Covenants, the first part, where the Lectures on Faith are, it actually says, “on the doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, originally delivered before a class of elders in Kirtland, Ohio.” So the “doctrine” in Doctrine and Covenants is the Lectures on Faith. Then, if you look at Part 2, It will say “Part 2, the covenants and commandments of the Lord.”

Scott Woodward:

Doctrine and Covenants.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That’s where the name comes from.

Scott Woodward:

So now covenants is becoming the word equivalent with commandments, which is the word equivalent with the revelations.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So you’ve just got to follow this lexicon that’s being laid out there.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And I should be clear that the covenants was the bigger part of the book. The Lectures on Faith were the first 74 pages. The following 179 pages were the commandments and covenants of the Lord. So the commandments and covenants were always more prominent, but some church members don’t realize that the Lectures on Faith were a major part of the Doctrine and Covenants. In fact, they’re what early church members would have referred to as the doctrine when they were referring to this book.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Lectures on Faith hang in there until the 1921 edition, and we’ll talk about that in a few minutes.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, so the doctrine in this case means teachings, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

It’s not like all of the eternal truths that we believe are in the theological lectures And then all the revelations are something other than eternal doctrine. That’s not it, right? So in this case doctrine means teachings. Here’s some lectures. Here’s some theological lectures. And then the second part is the revelations.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, so lectures on theology combined together with the revelations given to Joseph Smith, together called the Doctrine and Covenants. That’s 1835.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And the other thing is in 1835 there were a lot of key revelations given about the structure of the church. So section 107 appears in 1835.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That is a huge revelation.

Scott Woodward:

Yes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That denotes the presiding quorums of the Church, the First Presidency, the Twelve, the Seventy, the presiding bishopric, the patriarchs, so on and so forth.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And they do go back to earlier revelations, and just like you mentioned in our earlier episode, they kind of harmonize everything together.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. And this was front loaded, right? This revelation along with section 1 and section 20, the ones that were a little more regulatory in nature. Section 1 is the preface, and then section 20, and then that was followed immediately by what we call today section 107 because of their regulatory nature, their broad applicability to the whole church. Those were front loaded. So it was organized differently, right? It was organized by almost these revelations of the most importance to the whole church would be in the front of the covenants part of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Whereas today we just order them chronologically, correct?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, today’s Doctrine and Covenants is roughly chronological. There’s a couple exceptions.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But this was, just like you said, in order of importance. You’ve got to know the articles and covenants of the Church. That’s going to go early on.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Section 107, which describes the government of the Church, is going to go on.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And it also, like we said, has this huge section on the Lectures on Faith. And that is really the beginning.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Book of Commandments is kind of a failure-to-launch situation. The Doctrine and Covenants is sustained by the entire church, and this is where it formally enters into the scriptural canon.

Scott Woodward:

So do they have, like, a meeting where they all sustain it?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah, they do. In a book called How We Got the Doctrine and Covenants, it’s by Rick Turley and Bill Slaughter, came out a couple years ago, they actually document August 17th, 1835, there’s a sustaining vote, and here’s what they record: “On August 17, 1835, a general church assembly convened to take into consideration of the labors of Joseph’s writing committee had been charged with. In the afternoon of the conference, Joseph Smith and Frederick G. Williams being out of town at the time, the other two committee members, Oliver Cowdery and Sidney Rigdon, became responsible for presenting the new volume to those assembled and obtaining their views of it. One by one, the several authorities and the general assembly, by a unanimous vote, accepted the labors of the committee and testified to the book’s truth. With that vote, the Doctrine and Covenants became the Church’s third standard work along with the Bible and the Book of Mormon.” We don’t have the Pearl of Great Price yet, but on August 17th, 1835, the Doctrine and Covenants went from being scripture to being canon, and now we’ve got three books of scripture. We’re off to the races.

Scott Woodward:

I love that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They decide, while Joseph Smith is alive, to produce a new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, which, again, demonstrates it wasn’t a finished work. In 1844 they have done enough work to produce a new version of the Doctrine and Covenants, which hews very closely to the 1835 edition. In fact, almost word for word, except for minor corrections and stylistic changes, it’s the same.

Scott Woodward:

So 1844 is basically the same as 1835, but with stylistic changes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The minor changes, again, that idea that they’re correcting, they’re trying to get it right, it’s going to be pretty much the same, but then something happens in the summer of 1844 that causes another addition to the Doctrine and Covenants. And when I say 1844, most people are thinking not of the Doctrine and Covenants. They’re thinking of the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. So before they publish the Doctrine and Covenants, which they do in the fall, Joseph and Hyrum are killed in June.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They are able to add in a final section that’s entitled “The Martyrdom of Joseph Smith and His Brother Hyrum.” This commemoration, which is today section 135, has a complicated history, too, because you might have noticed until recently in the Doctrine and Covenants, it says this was composed by John Taylor.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Then, in the newest edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, it doesn’t say that.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s partially because it was an assumption that John Taylor had written it. John Taylor never claimed to be the sole author. He probably was one of the authors, but John Taylor was pretty badly wounded at Carthage Jail, too. And it’s possible he collaborated with some people, so they took John Taylor’s name off just so they wouldn’t accidentally leave out somebody who may have collaborated with him.

Scott Woodward:

So right now it’s an anonymous author.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. There are several new items added to this: section 101, section 111—section 101 and 102, both revelations regarding the redemption of Zion, were not included in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants. They’re included here. And then they add in a couple other sections that have to do with baptism for the dead. And the 1844 one doesn’t get a ton of attention, but it’s important because this is the Doctrine and Covenants that all Restoration movements agreed on. This is where, for instance, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Community of Christ diverge from each other. And the 1844 Doctrine and Covenants is where we all agreed. In fact, the next version of the Doctrine and Covenants, which comes out in 1876, is seriously affected by Community of Christ, the RLDS Church, whatever you want to call them.

Scott Woodward:

Wait, wait, so 1844 did add a few revelations to it.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Tweaked some things. And it is the final version of the Doctrine and Covenants that all restoration movements agree on.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, pretty much.

Scott Woodward:

Pretty much. Pretty much. I know that that’s a little bit complicated, but. . .

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s complicated because people don’t realize there are hundreds of restoration movements, and everybody has kind of their own thing.

Scott Woodward:

There’s so many.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But yeah, the major restoration movements, at least the biggest ones, and I hope I’m not hurting anybody’s feelings by saying that.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. I was just thinking, you and I were in Independence last month together, Independence, Missouri, with several of these restoration branches. Wonderful people. We made some good friends. I remember asking one of them about the Doctrine and Covenants, and he said, “No, we don’t have the Doctrine and Covenants as one of our standard works. We only use the Book of Commandments.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

I thought that was interesting. So, yeah, there’s variety there.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

There’s variety. Maybe I shouldn’t have even brought that up, but it’s there.

Scott Woodward:

It’s there. Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Next version of the Doctrine and Covenants, 1876. And this is the big one.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This is where probably the biggest changes are made since 1835, before or since. Orson Pratt oversees it. One of the things he does that we’re familiar with now is he reorganizes it so that it’s roughly chronological.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So instead of having the most important sections at the first, now it’s roughly when were they received, and they’re given an order. So you can kind of see the development as well.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But Orson Pratt also adds in 26 new sections to the Doctrine and Covenants.

Scott Woodward:

That’s a lot of sections.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That’s a lot. And some of these sections are key sections that are a really, really big deal to us. For instance, section 2, which talks about Elijah and his return, it’s an excerpt from Joseph Smith—History, that’s there.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Section 13, the keys of the Aaronic Priesthood, this is added for the first time. Section 109, the dedication of the Kirtland Temple. Section 110, the appearance of Christ, Moses, Elias, and Elijah in the Kirtland Temple. Section 121, which is the section every one of my students writes their paper on, is included because Orson Pratt includes it as well. And one key pattern you can see as to why he includes these sections is he’s including them under the direction of Brigham Young in response to the RLDS church—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—which has been founded by this point, and is basically claiming that they’re the church, and they’re saying that they operate by authority because the RLDS church was organized by people who had been ordained when Joseph Smith was the prophet. Brigham Young and Orson Pratt include a number of sections, like section 13 and section 110, which talk about priesthood keys.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, it seems like the two themes, the major two biggies, are priesthood and temple.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And those are points of contention between us and the Community of Christ at that time, or the RLDS Church at that time.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Because they’re going to go away from the temple, right? They’re going to go away from the temple ordinances as practiced in Nauvoo.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And in some ways delegitimize those.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And so this is the rebuttal back in some ways. It’s like, no, these are revelations Joseph received. Now let’s canonize them to show their legitimacy.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah. The RLDS/Community of Christ practice no form of the temple ordinances—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—as we understand them. Even baptisms for the dead. These sections are there to kind of say, yep, the temple ordinances do have foundations and do priesthood keys.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And there’s a couple other things. Now, probably the most controversial of the sections added is section 132.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And this is also our first example of decanonization. So in 1835, when the Doctrine and Covenants was published, there was an article on marriage. It wasn’t considered a revelation. It was a declaration on marriage. It’s not something that they’re claiming was received by direct revelation. It’s something that a group of responsible church leaders set down and wrote to explain the church’s view on marriage, which is what the article on marriage did.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, Orson Pratt removes the article on marriage. He decanonizes it, and he adds into the canon section 132, which is the revelation on eternal marriage, and maybe more controversially, plural marriage as well.

Scott Woodward:

Also a major point of contention with the RLDS church at that time: Did Joseph Smith actually introduce plural marriage or is this a Brigham Young invention that he’s pinning back on Joseph, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So 132 is the proof that this came originally with Joseph.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And 132 is key. I mean, we’ve done a whole podcast on section 132—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—and how it establishes basically that plural marriage and eternal marriage both come from Joseph Smith, that they were not theological innovation that he just came up with, they were a revelation given to him by commandment by God.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now one last addition, and that is they add in section 136, which is a revelation given to Brigham Young at Winter Quarters. And so I don’t know if this was for the RLDS church or not, but it was just basically to show that Joseph Smith’s successors in the presidency would also add to the Doctrine and Covenants, and this is one of the most prominent examples, the other one being Section 138, which comes from Joseph F. Smith.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So 1876, big year for the Doctrine and Covenants. First example of decanonization, where the article on marriage is removed.

Scott Woodward:

Do you think it was removed because it could appear to be in conflict with 132?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, I think. I also think that in their mind, a revelation is more significant than a declaration.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We kind of danced around this a little bit, but the implication with a declaration is that a bunch of church members got together and under the influence of the Holy Ghost wrote it.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

A revelation is kind of what we talked about before, where it’s a commandment given directly from God to a church leader, in this case Joseph Smith, and they felt like that was more significant, that it replaced the article on marriage, essentially. And it was received after the article on marriage. The article on marriage is written in 1835. Section 132 is a revelation given in 1843. So it does sort of supplant everything that the article on marriage said.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Okay. Makes sense.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay. So 1876 is a big year and massive amounts of material. The biggest year for decanonization, though, is 1921. 1921, a scripture committee consisting of Joseph Fielding Smith, John A. Widtsoe, and James E. Talmage is appointed to oversee a new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They add to the Doctrine and Covenants Official Declaration 1, which ends the practice of plural marriage. And here’s the big thing: they take out the Lectures on Faith. So this is the most significant instance of decanonization.

Scott Woodward:

They took out the doctrine of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, yeah, they basically do. But now, there’s plenty of doctrine, and so they just keep the title, but the Lectures on Faith are removed.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, why? Why did they. . . Why do they take out the Lectures on Faith?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This is still sort of controversial.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Lectures on Faith are early.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And they’re never presented to the church as revelations. They’re instructions. They’re theological lectures. They’re pretty open and transparent about this.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

When Joseph Fielding Smith is asked later on why the Lectures on Faith were removed, here’s the reasons he stated: This is a 1940 interview he gives.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, so 19 years later.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah. So, 1. He says the lectures were never received by Joseph Smith as revelation.

Scott Woodward:

True.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

2. The lectures were only instructions relative to the general subject of faith and are not the doctrine of the church.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

3. The lectures are not complete concerning their teachings on the Godhead. That’s true.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

One of the lectures, lecture five, says that the Father is a personage of spirit and talks about the Holy Ghost as the mind of God, not like He’s a separate person. And so here’s President Smith’s reason number 4. “It was thought by Elder James E. Talmage, chairman of the committee responsible for the lectures’ removal, that to avoid confusion and contention on this vital point of belief on the Godhead, it would be better not to have them bound in the same volume with the commandments and revelation.” Now, can I add in a personal aside here?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I took a class from Joseph Fielding Smith’s grandson, Joseph Fielding McConkie.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And in the class he asked each of us to give a presentation, and I chose the Lectures on Faith. And Brother McConkie, who would always like, quote, “My dad said,” and “My granddad said,” because his dad was Bruce R. McConkie and his granddad was Joseph Fielding Smith, said a couple times that he felt like the Lectures on Faith should have never been removed from the Doctrine and Covenants.

Scott Woodward:

Interesting.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So I’m giving my presentation in class, and I get to this point of why were the Lectures on Faith removed, and I made the statement, the Lectures on Faith were removed by a scripture committee consisting of Joseph Fielding Smith, James E. Talmage, and John A. Widtsoe because of some questionable doctrine. And I said that, and Joseph Fielding McConkie shot out of his chair and started, like, yelling at me. It was so scary. But the thing I remember him saying specifically was, “There’s no wrong doctrine! My granddaddy got outvoted!” And I was like, I will say whatever you want me to say, man. I’m just so scared right now.

Scott Woodward:

What do I got to do for a good grade? You just tell me.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, what do I got to do? But that was his opinion, and again, this is all hearsay, but I’m guessing that was what was passed down from his granddad and his dad. And he, again, went over these discrepancies and said there’s easy ways to reconcile them, so we should have just kept the Lectures on Faith in. And I should add, by the way, that when we’re decanonizing, all we’re doing is taking something from the canon and removing it. We’re not saying it’s not scripture anymore. I still use the Lectures on Faith in my classes, especially Lecture Three. Lecture Three was quoted extensively in General Conference on several occasions. Everybody should read the Lectures on Faith. All they were saying was that we’re not going to use the Lectures on Faith as a measuring rod. And again, whatever Brother McConkie said, there may have been some controversy about the Lectures on Faith being removed.

Scott Woodward:

Definitely. Okay, let me give you some quotes from the Lectures on Faith, listeners. Here you go.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay.

Scott Woodward:

At the end of every lecture, there’s always questions and answers. It’s kind of this Q&A, back and forth. What’s this called?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The catechism.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, it’s kind of like a catechism, yeah. So here you go. How many personages are there in the Godhead? I’ll give you all a second to answer that question in your mind, and then I’ll give you the answer from Lectures on Faith. Okay, correct answer? Two: the Father and the Son. And now turn the page a few pages here. Question: “Do the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit constitute the Godhead?” Answer: “They do.” That sounds like three. It sounds like three. “Do the Father and the Son possess the same mind?” Answer: “They do.” “What is the mind?” Answer: “the Holy Spirit.” So, yeah, there’s doctrine like that that can seem a little—and these are written most likely by Sidney Rigdon, right? Joseph Smith’s fingerprints seem to be on one or two of these lectures, but mostly seems to come from Sidney. So there is ambiguous authorship added to that, some sketchy—like, what are you supposed to do with that doctrine about the Godhead? Compare that, for instance, to 2 Nephi 31, “The Father the Son and the Holy Ghost are one,” or 3 Nephi 11 where Jesus preaches about the Godhead, about the three, right? Just—I can see why there was some controversy as to what to do with that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And yeah, there you go. The answer was, what if we just decanonize it? We’re not saying that it’s not valuable. We’re just saying that it’s not canon.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s not canon.

Scott Woodward:

This is not the standard by which we are going to measure doctrine.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Right, right. And I want to go on record as saying I love the Lectures on Faith. I think everybody should read them. I think they’re great. Joseph Smith sustained them, if he didn’t write them. He may have written some of them.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But I also think Elder Talmage and the committee were right.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I think the Lectures on Faith are scripture but maybe not a measuring rod to be used to test other scripture.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So the 1921 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants is our biggest example of decanonization. The Lectures on Faith are removed. That is by far far the biggest removal of material from the Doctrine and Covenants in its history.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, that’s a big chunk.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We don’t get another edition of the Doctrine and Covenants until 1981, and this one we’ve also mentioned extensively.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It adds in sections 137 and 138, which were originally placed in the Pearl of Great Price. That is Joseph Smith’s vision of his brother in the Celestial Kingdom and Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the visit of Christ to the spirit world, which is—I love section 138. It’s in the running for my favorite section of the Doctrine and Covenants. It’s so, it’s—

Scott Woodward:

So good.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

If we don’t add anything to the Doctrine and Covenants, it is the perfect way to end the scriptures because it’s this big reunion where Adam and Eve and all the faithful prophets are sent by Christ to teach the gospel in the spirit world. I love it. I’m so glad they added it. But it’s also a good example of not something that was brand new.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We did add something brand new, Official Declaration 2, but by 1981, I mean, section 138 was received in 1918, so that’s several decades of it kind of being out there. It’s percolating.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s being used a lot by members of the church, and the First Presidency and Twelve recognized, hey, this is super significant.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It probably needs to go from being scripture to canon. It’s a measuring rod we should use.

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And I will say most of our knowledge about the postmortal spirit world is section 138 stuff. It’s totally invaluable.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. It actually reveals new doctrine.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So in other words, the truthfulness of the teachings in 138 couldn’t be measured by other canonized scripture very well because it’s actually breaking new ground. He’s asking questions that were prompted by scripture, right? Peter’s statements about Jesus going into the spirit world that left him questioning some things about exactly how that worked.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And that leads to an explosion of insight that clarifies doctrine and then adds some stuff we didn’t even know. So, yeah, when it’s new doctrine like that that came to the president of the church, and then later on, another president of the church then later says, we’d like to propose this for canonization, like, that’s exactly how it works, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Revelation to a prophet, later canonized by another prophet, sustained by the church. Booyah. Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Absolutely. Yeah. So glad it’s there. And that is technically, 1979, 1981, the last time we went through the formal canonization process. Official Declaration 2, 137, 138 are added to it. But it’s not the newest edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Scott Woodward:

Ah, shoot.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The newest edition of the Doctrine and Covenants is from 2013. It’s 2023 as we’re recording this. It’s less than 10 years old. And this one was big, too. There weren’t any canonizations made, but it might surprise people to know that 75 sections of the Doctrine and Covenants were changed in the 2013 edition.

Scott Woodward:

Wait a minute, wait a minute. So, whoa, what does that mean? What was changed?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Well, this is where our discussion of canon becomes tricky, too, because we would say the text of the revelations is canon, but the historical introductions, the little italicized introduction before each section, is not canon.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And that’s actually where most of the changes came from. You can go to the Joseph Smith Papers site and download a PDF that actually highlights in yellow all the parts of the Doctrine and Covenants that were changed. And just so you don’t have to, but you can if you want to, I have looked through every single page, and almost all the changes are in the section headings.

Scott Woodward:

Ah, so the revelations themselves were not really touched. There’s a few, like, tweaks, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

There were a couple changes made.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

There were a couple changes made, and I’ll go through those in just a second.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But for the most part, it was, hey, we were doing the Joseph Smith Papers, we got more accurate information, it seems like this section was actually received here instead of here. For instance, section 99 chronologically should be somewhere in the 70s of the Doctrine and Covenants, it was just misdated when they put it in.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They chose not to change any section numbers because by this point we’ve been using the section numbers since 1876, so we kept them there.

Scott Woodward:

We’d have to overhaul all the curriculum that ever references any of these sections if we change the numbers of the section.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

That’d be a problem.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But that doesn’t mean that these supporting materials aren’t important. For instance, Official Declaration 1 and Official Declaration 2 didn’t have any kind of historical introduction prior to 2013. Now they do. And it’s the closest we get to an official statement on the end of plural marriage, which is Official Declaration 1, and the end of the race and temple policy in the church, which you and I have done, I don’t know, six episodes on talking about.

Scott Woodward:

Full series on, yep.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But it is significant that they chose to include a historical introduction to Official Declaration 2 that basically said Joseph Smith did allow several people of African ancestry to be ordained to the church, and it was stopped after Joseph Smith.

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And it also states this: “Church leaders believed that a revelation from God was needed to alter this practice and prayerfully sought guidance. The revelation came to church President Spencer W. Kimball.” And that’s a big deal because I would point out that Official Declaration 2 is not the revelation.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s an acknowledgement of the revelation. But this historical introduction is acknowledging a revelation did come to him.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, that’s good.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, there were changes made to the actual canon of the Doctrine and Covenants, too.

Scott Woodward:

Wait, wait, wait, wait. Is this going to be pretty major? Some major changes to the text?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Fasten your seatbelts, okay?

Scott Woodward:

Oh, shoot.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This could wreck some testimony, so hang in there, okay? So. . . all right, here we go. So, section 35, verse 13, was changed from “thrash the nations by the power of my spirit” to “thresh the nations by the power of my spirit.”

Scott Woodward:

Wait, wait, wait. It was changed from thrash to thresh.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, so thrash, T-H-R-A-S-H, to thresh, T-H-R-E-S-H.

Scott Woodward:

Okay. Which is more of a winnowing term, right? Of grain.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Right? To thresh grain.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. A kid I grew up with put D&C 35:13 because to say “I will thrash the nations by the power of my spirit” sounds like we are going to beat the nations into submission. When they looked at the earliest copy of the revelation, it seemed like the term thresh, which is an agricultural term. It just means you separate the useful part of the plant from the non-useful part. Like, if you’ve ever shucked corn, you’ve threshed. That’s a change that happens to the canonical text.

Scott Woodward:

So your friend who put that on his missionary plaque, that was a little, uh, humiliating for him that he’s now, he’s a humble farmer rather than some classroom bully. Good job.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I hope he’s doing okay.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. I’ll reach out to him and see if this totally wrecked his testimony.

Scott Woodward:

Perfect.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And then the other changes are things like, I mean. . .

Scott Woodward:

Hyphenated words.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. In D&C 127:12, “the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” with a lowercase t in the “the” was changed to “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” with a uppercase T in the “the.” They did that in several places. They also did that in 136:2 and Official Declaration 1. Like I said, we’ll post in the show notes all the changes that were made. It’s mostly semicolons, dashes, and periods that were removed. They did change the spelling of James Covel in section 40, but it’s because we found census records. We think his name was always spelled wrong, and so we tried to align it with that, but nothing major, is what I’m saying here, in the 2013 edition.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It does just show, though, that, like they said, the Doctrine and Covenants is living. It’s dynamic. If we can find stuff that’s wrong, we’ll correct it, but we didn’t find very much in the canonical text that was wrong, so we didn’t really make that many changes to it, but we did make some changes.

Scott Woodward:

And this is all fruits of the Joseph Smith Papers Project, right, where now we’ve got, like, highly trained historians combing through as original manuscripts as we can get—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

—looking at census records, looking at all the historical context. And from that, we only get a few changes, mostly in the historical introductions—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

—and then just some grammatical stuff, it sounds like, in the actual revelations themselves. Is that a fair summary of what you just said?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, totally. Minor changes to the text, which has happened in every edition of the Doctrine and Covenants as they’ve tried to weed out all the mistakes that come into it.

Scott Woodward:

So our burning question of the day today was, how is the canonization and decanonization process Illustrated in the development of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And Casey, you’ve taken us on a journey today. This is very interesting. There’s been a lot of changes from first attempt to publish Joseph’s revelations in 1833 with the Book of Commandments until what we have today in the 2013 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

I guess my final question for you is, therefore, what? Like, why should this matter? Why should we care as members of the church? I mean, this is our scripture. Of course it matters on that level, but like, I don’t know, what does this do for you? Why is this valuable? What do you want to say about that?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Well, I think the major takeaways are this: number 1. We’ve emphasized this in both episodes, but scripture is given all the time. Anybody that speaks through the power of the Holy Ghost is receiving scripture. 2. Canon is how we measure what genuine scripture is. And canon is more rare when there’s an addition made to it, but that’s because canon is something that takes a little while to actually be established as canon. We didn’t put Joseph F. Smith’s revelation into the Doctrine and Covenants immediately; we took it out for a test drive. We spent a couple decades mulling it over, thinking about it, using it in our teachings before we realized it’s such a big deal. It needs to be part of the canon.

Scott Woodward:

This is section 138.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Section 138.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And the last thing I would say, and you’ve said this so eloquently so many times, is that scripture is living and dynamic and changing, and the Doctrine and Covenants illustrates that, that it really shouldn’t cause you any heartburn if they come out with a new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants and there’s changes to the text, because we’re doing the best we can to try and get it right.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The whole process has been incredibly transparent—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—where they’ve published all the changes that they’ve made, they’ve publicly announced when they were going to canonize or decanonize something, or even in the case of the 2013 edition, if they made the smallest change, I mean, even the deletion of a period to the commandments, that they’ve publicly stated they’re doing that.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, in the future, because scriptures are electronic now and publishing them electronically isn’t as arduous as publishing them in print, it’s possible we could get a new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants with more frequency than we have in the past. In the past, it’s been kind of a once-in-a-generation occurrence. It’s possible that could change in the future.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But one of the things members of the church need to remember is that the Doctrine and Covenants is being created. We’ll canonize things. It’s possible we could decanonize things. We should expect that to happen. It’s living. It’s dynamic. It’s changing. And that’s a great thing. That’s a wonderful thing that every member of the church should be thrilled about to get to participate in the creation of new scripture, which anybody can participate in, and the creation of new canon, which we also get to participate in in our role as sustaining members of the church.

Scott Woodward: