Revelations and Translations |

Episode 10

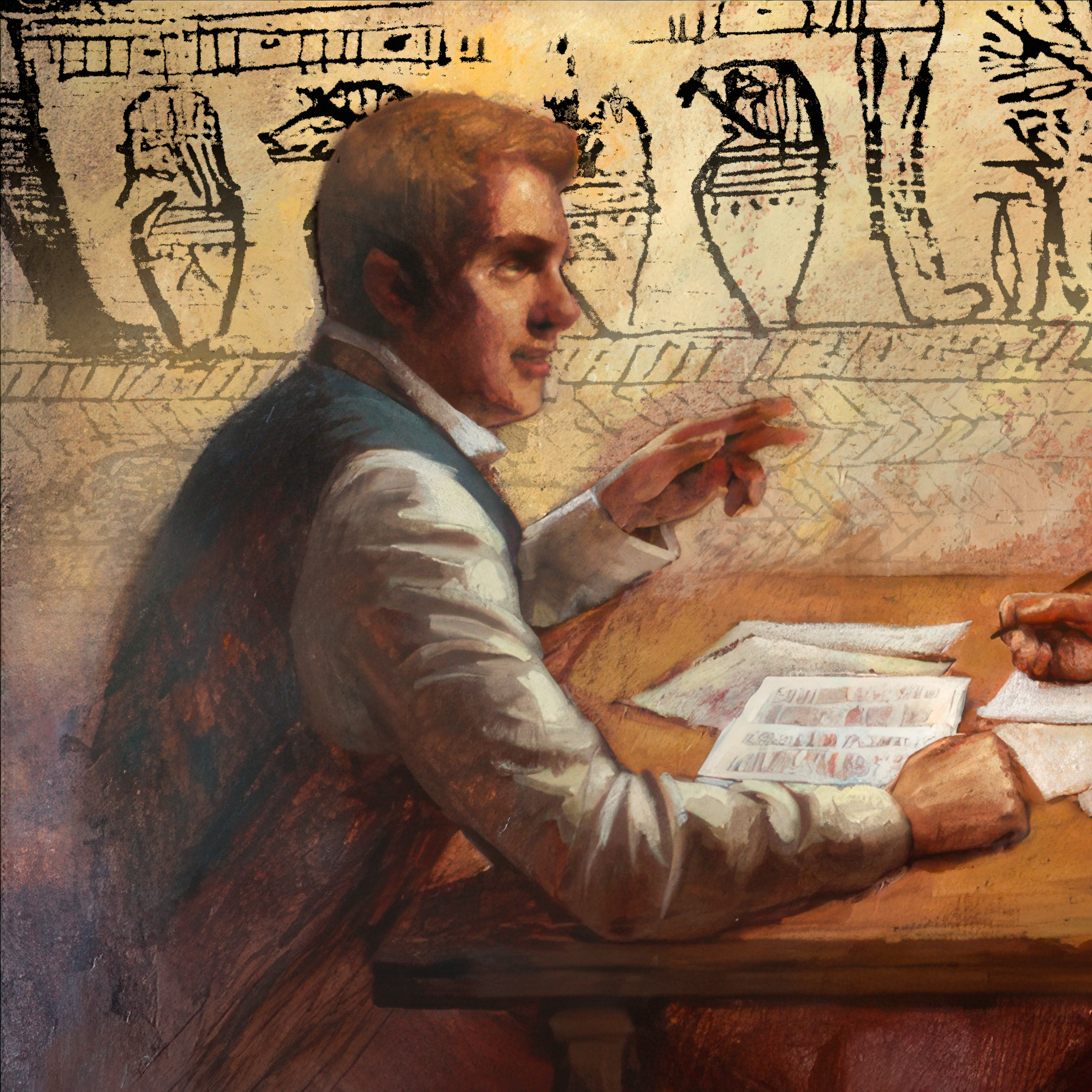

Q&R with Dr. Kerry Muhlestein! Tough Book of Abraham Questions

70 min

So there was, in 2nd century BC Egypt, an indisputable, multicultural sharing of religious ideas between Jews, Greeks, and Egyptians. How should that fact influence how we evaluate Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the Abraham facsimiles in general and individual hieroglyphics on the facsimiles specifically? On a related note, some of Joseph’s descriptions of Facsimile 2 contain temple themes, saying that more will be revealed about those in the temple. Can Egyptologists today read those hieroglyphs, and are they actually connected in any way to what we learn about in our modern temples? Also, Dr. Robert Ritner is an Egyptologist who has critiqued LDS scholarship on the book of Abraham. Has he been adequately responded to? And finally, what are the top three most solid intellectual evidences for the book of Abraham having ancient connections which Joseph Smith could not have known about? In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we dive into all of these questions and more with Dr. Kerry Muhlestein, an Egyptologist and scholar on the book of Abraham.

Revelations and Translations |

- Show Notes

- Transcript

Biography of Kerry Muhlestein

Kerry Muhlestein received his bachelor’s from BYU in psychology with a Hebrew minor. As an undergraduate, he spent time at the BYU Jerusalem Center in the intensive Hebrew program. He received a master’s in Ancient Near Eastern Studies from BYU and his Ph. D. from UCLA in Egyptology, where in his final year he was named UCLA Affiliate’s Graduate Student of the Year. He is director of the BYU Egypt excavation project. He was selected by the Princeton Review in 2012 as one of the best 300 professors in the nation. He was also a visiting fellow at the University of Oxford for the 2016-17 academic year. He’s published nine books, over 60 peer-reviewed articles, and has done over seventy-five academic presentations. Now, we’re going to keep going. He and his wife, Julianne, are the parents of six children, one grandchild. Together they’ve lived in Jerusalem, where Kerry has taught there on multiple occasions. He’s served as the chairman of the National Committee for the American Research Center in Egypt, serves on their Research Supporting Member Council and on the Board of Governors. He’s also served on a committee for the study of Egyptian antiquities and currently serves on their Board of Trustees and is vice president of the organization and has served as their president. He has been the co-chair for the Egyptian archaeology session of the American Schools of Oriental Research. He’s also a senior fellow of the William F. Albright Institute for Archaeological Research. He’s involved with the International Association of Egyptologists and has worked with the Educational Testing Services on their AP World History exam.

Questions from this Episode

- I finished your most recent episode on the book of Abraham, and I’m still a little confused about the facsimiles. I understand the cross-cultural influences of Jews living in Egypt and how the story of Abraham was depicted in other facsimiles of the time, but can you further explain or clarify the implications of that for Joseph Smith’s translations of these facsimiles? For example, are you saying it is possible a Jewish person took what Egyptians depicted, like on the facsimiles, and then wrote their own story, which was the story of Abraham, sort of on top of that to accompany the same images, and that that’s what’s depicted in the papyri that Joseph had in his possession?

- I completely agree with your discussion of viewing the facsimiles within a cultural framework of appropriation and re-application, but what can we make of examples where Joseph directs the reader to specific hieroglyphics, such as his explanation of Numbers 2, 4, and 5 in Facsimile 3, which mention the characters above the figures’ heads or hands. This isn’t a picture being given additional layers of meaning but actual text that can be read and does not seem to match what Joseph suggests.

- Dr. Cooney of UCLA and Dr. Ritner of the University of Chicago commented on the lion couch scene talked about by Dr. Muhlestein and on an episode of your podcast. They both state that the name Abraham has nothing to do with the couch or the lion. They said that it appears in a list of biblical names and is completely unassociated with the picture. They say that it is just one of the many names listed as a part of a Coptic magic spell. Dr. Muhlestein, could you respond to this specific objection?

- It seems that the book of Abraham and other canonized scriptures, depend on much of the Old Testament being literal, such as Adam and Eve, the Tower of Babel, Abraham, Moses’ exodus, so on and so forth. I found that many biblical scholars do not believe these stories to be literal. How can I reconcile the early church’s truth being contingent upon these stories being literal?

- In your episode on the Abraham facsimiles, you brought up some proofs of the book of Abraham, like Olishem. As a non-specialist, it can be hard to discern which proofs might only be acceptable to Latter-day Saint scholars and which ones are genuinely accepted by Egyptian scholars who are not church members. Could you please share the top three most solid intellectual evidences for the book of Abraham having ancient connections that Joseph Smith could not have known of?

Related Resources

Gospel Topics essay, “Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham.” churchofjesuschrist.org.

Muhlestein, Kerry, Let’s Talk about the Book of Abraham. Deseret Book, 2022.

Gee, John, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, Deseret Book, 2017.

Scott Woodward:

So there was, in 2nd century BC Egypt, an indisputable, multicultural sharing of religious ideas between Jews, Greeks, and Egyptians. How should that fact influence how we evaluate Joseph Smith’s interpretations of the Abraham facsimiles in general and individual hieroglyphics on the facsimiles specifically? On a related note, some of Joseph’s descriptions of Facsimile 2 contain temple themes, saying that more will be revealed about those in the temple. Can Egyptologists today read those hieroglyphs, and are they actually connected in any way to what we learn about in our modern temples? Also, Dr. Robert Ritner is an Egyptologist who has critiqued LDS scholarship on the book of Abraham. Has he been adequately responded to? And finally, what are the top three most solid intellectual evidences for the book of Abraham having ancient connections which Joseph Smith could not have known about? In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we dive into all of these questions and more with Dr. Kerry Muhlestein, an Egyptologist and scholar on the book of Abraham. I’m Scott Woodward, and my co-host is Casey Griffiths, and today we dive into our tenth and final episode in this series dealing with Joseph Smith’s non-Book-of-Mormon translations and revelations. Now let’s get into it.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And hello, Scott.

Scott Woodward:

Hey, Casey. How you doing, man?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Good. How are you doing?

Scott Woodward:

Oh, splendid. Splendid.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Splendid.

Scott Woodward:

I’m excited to dive into some questions. We’ve got some great questions from our listeners, and we have a really special treat for them, don’t we, today?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We do. We have a wonderful guest. With us is Dr. Kerry Muhlestein. Say hi, Kerry.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Hey, how are you?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We’re very, very excited to have Dr. Muhlestein with us.

Scott Woodward:

Yes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And just to give you a sample—his bio is long, but we really want to establish his credentials here.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, it’ll put you to sleep. You should skip it, probably.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Well, well, we just want to know what a blessing it is to have you with us, so I’ll launch in. Kerry received his bachelor’s from BYU in psychology with a Hebrew minor. As an undergraduate, he spent time at the BYU Jerusalem Center in the intensive Hebrew program. He received a master’s in Ancient Near Eastern Studies from BYU and his Ph. D. from UCLA in Egyptology, where in his final year he was named UCLA Affiliate’s Graduate Student of the Year. He is director of the BYU Egypt excavation project. He was selected by the Princeton Review in 2012 as one of the best 300 professors in the nation.

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He was also a visiting fellow at the University of Oxford for the 2016-17 academic year. He’s published nine books, over 60 peer-reviewed articles, and has done over seventy-five academic presentations. Now, we’re going to keep going. He and his wife, Julianne, are the parents of six children, one grandchild. Together they’ve lived in Jerusalem, where Kerry has taught there on multiple occasions. He’s served as the chairman of the National Committee for the American Research Center in Egypt, serves on their Research Supporting Member Council and on the Board of Governors. He’s also served on a committee for the study of Egyptian antiquities and currently serves on their Board of Trustees and is vice president of the organization and has served as their president. He has been the co-chair for the Egyptian archaeology session of the American Schools of Oriental Research. He’s also a senior fellow of the William F. Albright Institute for Archaeological Research. He’s involved with the International Association of Egyptologists and has worked with the Educational Testing Services on their AP World History exam. That is—

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—a lot.

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But what we’re trying to get across here is Kerry is really qualified to answer questions about Egyptology and particularly the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Yes.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Or qualified to have introductions that put people to sleep and they don’t hear anything else we say. But yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We just wanted people to know you’re—got the skills to pay the bills.

Scott Woodward:

Yes. Kerry, that’s a super impressive bio. Can you just help our listeners understand, like, how did you get involved in Egyptology? What led you down this path?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, a number of things. The very short story is that as I was trying to understand the ancient world and the texts of the ancient world—I am an archaeologist, but even more than that, I’m what you’d call a philologist, someone who studies texts and languages. As I loved the texts of the ancient world, I came to recognize that there’s no way you can really understand them if you don’t understand symbolism, symbolic language, symbolic action, and so on. And no one is as good at symbolism as the Egyptians, so I thought I would just kind of start to dabble in that, and I got hooked and fell in love and just couldn’t stop. So that’s kind of the short version. Maybe to follow up just a little bit, I’ve been accepted at Chicago and U Penn and on the wait list at Yale when an Egyptologist from UCLA came and spoke at BYU as I was just finishing my thesis there, and he was so good, and he was doing exactly the kinds of things I was interested in. And it turns out in a small—in any discipline, but especially a small discipline like Egyptology, it’s who you study with matters more than where you study, and it turns out that this guy is one of the best Egyptologists in the world, especially in terms of the language. Like, he wrote the linguistic grammar of the Egyptian language and so on.

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Incredibly brilliant and a wonderful human being. So I decided to go study with him. So I deferred a year and applied to UCLA and turned down these other schools and went and studied with him, which was one of the best things I ever did, but I also ended up—partway through my PhD program we brought in another Egyptologist who specialized in archaeology named Willeke Wendrich, who’s right now the president of the International Association of Egyptologists, and so she really, really got me into archaeology. And so most of the time you do either one or the other. And I was primarily in linguistics but did a lot of archaeological studies with her, and then that’s how I got going down the archaeology path. So I do both.

Scott Woodward:

Wow. And did the book of Abraham itself serve as any kind of a launch pad for your interest, or did it go the other way?

Kerry Muhlestein:

No, it’s the other way. Actually, I really didn’t want to do book of Abraham because I don’t like controversial things. Part of the reason I became a little un-enamored of the biblical world is it’s so hard to write about it without having to deal with what they call minimalists and maximalists—well, I guess what we do. You know, this person says, “There’s no way you could read any historicity into it,” and someone else says, “There’s no way you can”—and I just—I’m tired of dealing with that stuff, and I thought there was less in Egyptology. So I went that way and had intentionally planned to not deal with the book of Abraham at all. In fact, I was interested in the day of Abraham, the era of Abraham, largely because I was interested in that period in Egyptian history, but also in the Exodus. But so many people asked me so many questions that I thought, well, after several years of my PhD program, I thought, well, I should at least look into this a little bit so I can give some cogent answers. People just kind of assume if you’re an Egyptologist in the church that you know something about the book of Abraham. So, I hated to know nothing. And that actually, because people asked me some questions about that, and I hadn’t really looked into it, I taught some things that were incorrect about Egyptology, but that all of Egyptologists were teaching, until actually an article by Robert Ritner was pointed out to me that talked about the reality of human sacrifice, and I thought, “Wow. I’ve been teaching this all wrong all along.” So I wanted to look into why. What was the reasoning behind there would be human sacrifice in ancient Egypt since everyone thought that they didn’t do that kind of a thing? And that became my dissertation and then a book and a whole bunch of articles and going around and speaking about it to Egyptologists all over the world, and that was less about the book of Abraham and more about a book of Abraham thing that inspired me to get into it. But eventually, as I started to study the book of Abraham to be able to answer things that people ask me, I just fell in love with the mystery of all the questions that we couldn’t answer. So maybe I can speak to that just a little bit as well because it will undergird everything that we talk about for the rest of this time that we spend together.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, please.

Kerry Muhlestein:

For me—I understand people saying I do apologetics or saying I’m an apologist, and there’s some truth to that, but it’s not the way I approach things. For me it has always been I want to understand what’s going on. And that’s how I got into it, just wanting to answer people’s questions and then saying, “Wow. We don’t understand this. What can we do to understand it? Oh, we don’t understand this. What can we do to understand it?”

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Kerry Muhlestein:

And so my point of view, my frame of reference and my ability to research has always been just kind of guided by, “What’s really happening? What’s going on here?” Now, I will say I’m different than many others in that I allow revelatory information as a source of knowledge as well, but still it’s guided by wanting to know what is really going on, and how do we fit, like, this piece of evidence, this piece of evidence, and this piece of evidence that don’t seem to jive with each other? And that happens in Egyptology all the time. It happens in all research. It happens in any scientific endeavor all the time. And our job is then to say, “Well, how do we get these things to fit together? And if not, why not? What’s going on? What—are we asking the wrong questions? Are we looking at this the wrong way?” And so that’s been the guiding principle behind all of my research in the book of Abraham, is just to say, “What is happening here?” and to disabuse us of wrong ideas and of wrong approaches and to see if we can do a little bit better.

Scott Woodward:

Well, tremendous. Well, just from those on the receiving end of what you have done so far, we want to say thank you. We have highlighted your work throughout our series, your Let’s Talk About book, some of the other things you’ve done on Pearl of Great Price Central—so your work is helping the rest of us who are not Egyptologists, so thank you so much.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Ah, it’s just good, clean fun.

Scott Woodward:

Here’s maybe a first question we can start out with from a listener. This is Annie. Annie said this: she said, “I finished your most recent episode on the book of Abraham, and I’m still a little confused about the facsimiles. I understand the cross-cultural influences of Jews living in Egypt and how the story of Abraham was depicted in other facsimiles of the time, but can you further explain or clarify the implications of that for Joseph Smith’s translations of these facsimiles? For example, are you saying it is possible a Jewish person took what Egyptians depicted, like on the facsimiles, and then wrote their own story, which was the story of Abraham, sort of on top of that to accompany the same images, and that that’s what’s depicted in the papyri that Joseph had in his possession?” How do you want to talk about that, Kerry?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, so there are a number of things I think we should address here, so I’ll try and address them, hopefully one at a time and in a way that makes sense, so.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, please.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Let’s back up. First of all, as I said, often we need to think about the questions we’re asking and the assumptions we’re making and see if we can get those out in front of us. I think that’s the really important thing in research is to put in front of you, what are your original questions, what are the assumptions and what are the lenses you’re bringing with you? So for example, big picture, there are lots of people who assume that you can be objective about research and about coming into things, right? One of the things, there’s a whole bunch of silliness that has gone on with postmodern thinking and so on and so on, but there are also some really useful things. One of the really useful things is that there are no unbiased ways of approaching topics, especially topics that have anything to do with what we don’t know. There’s no unbiased way. There’s no objective way. And so for someone to say, “Well, rejecting religious ideas or rejecting revelation or anything along those lines, that’s more objective.” That’s just wrong. It’s just plain wrong.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Kerry Muhlestein:

So I’ve always found it interesting because I believe we will come closer to being able to get around our biases and our initial assumptions if we’re just upfront about what they are, if we can recognize them in ourselves. This isn’t true just of doing research. It’s true about how you deal with humans and everything else. If you can kind of self-analyze enough to say, “Here is my objectives and my assumptions. And now that I know that, how can I work with that and try and see things as clearly as possible, knowing that I have that,” right? And so I’ve tried to do that all along. I’ve had a lot of people who’ve said, “No, no, no. You can’t do that. It’s—you have to reject all religious things. That’s the only objective thing,” which is so actually subjective to say and so biased and so—it’s just ironic. So I’m just going to say up front let’s be aware of what our original assumptions and biases are. So we need to ask that about the questions about the facsimiles. The initial assumption most people make is that Joseph Smith is telling us how an ancient Egyptian would have interpreted these. And I’m going to be careful here, so I hear people say all the time, how Joseph Smith translated them. He’s not translating symbols. You don’t translate symbols, right? I mean, we can use that word actually accurately, but not in the way we usually mean when we say translate. So I think explain is maybe a better word.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Kerry Muhlestein:

He makes reference to hieroglyphs and what they say, but he never actually translates any of them on any of the facsimiles. He does talk about some of them and say, well, they mean this, or they’re about this, or they say this, but he doesn’t give us a translation. Mostly what he does is give us explanations of symbols. And that tells us—symbolism is a language, and that’s why we could talk about translating that language, but the problem is that symbolism is inherently designed to yield more than one meaning, or layers of meanings or facets of understanding. That’s one of the advantages of symbolism. It’s part of why our modern culture is divorcing itself from symbolism, because we’ve become very legalistic. And if you’re legalistic, you need one thing to mean one thing. It can’t mean two things, right? That causes liars all sorts of problems and courts all sorts of problems. So, we’re divorcing ourself from that point of view. But that’s the idea of symbols, is that they can yield more than one meaning. And so an explanation is going to be an explanation of one way of looking at it, and a good explanation will include that there are probably several ways of looking at this.

Scott Woodward:

Sure.

Kerry Muhlestein:

So that’s an important initial assumption along with the idea that recognizing that most people think, okay, Joseph Smith is telling us what an average ancient Egyptian would have thought. And even that gets tricky, because we don’t know much of what the average ancient Egyptian would have thought, and what we do know is not from this time period. So these were created around 200 BC, the drawings that Joseph Smith is reproducing as facsimiles, and most of what we know is from, say, around 1200, 1500 BC. So that automatically becomes difficult because the way you interpret, explain, or translate a symbol will change over a thousand years, just as much as, like, you know, we teach something—for the King James Bible, we’re often have to say, well, that’s not really what the word meant in the day that they were doing this 500 years ago, much less a thousand years ago, right?

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Kerry Muhlestein:

So that’s something that becomes very difficult for us, and as Egyptologists, we have to admit that there are a lot of things we don’t know about how things were interpreted or understood by Egyptians in 200 BC.

Scott Woodward:

So you’re saying that’s, like, a blind spot in the current discipline of Egyptology is the 200 BC time period in terms of what Egyptians would have thought and understood these things meant.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, for a couple of reasons. One of them is just time. A lot of time has passed, and cultures change. The way people look at things and understand them changes. And the second is that you are dealing with a time period where there is a lot of multicultural infusion. And as Egyptologists, we definitely understand that. There’s no doubt there’s been a huge Greek influence. The Greeks are ruling Egypt at the time. These are people that came with Alexander the Great, so Hellenistic or Greek culture, you’ve had a huge influx of Jews and then people from all over the place. So there’s a real mixing of cultural ideas and understandings, and that’s going to affect things as well. So just as an example, if we were to look at the hypocephalus, which is what—Facsimile 2 is a facsimile of a kind of drawing called a hypocephalus. We have several of them. And for a long time Egyptologists kind of would argue over some of the figures that are commonly used in hypocephali, including in the one that is Facsimile 2. They’d say it means this, and others would say, no, it means this, and so on and so on. The problem was we weren’t finding any Egyptian documents that labeled, like, “This is this character, and this is this character, and this is this character.” And then we’d have to know that first, and then we’d have to say, “Okay, well, how did they view that character in that time period?” You know, this person, I should say, or this god, or this being or something along those lines, you know? So that’s a two-step process: to know who it is and then, well, how did they think of them and how were they presented in that time period? And we can’t do either one of those very well. Well, eventually, Dr. John Gee from BYU did find a hypocephalus where a number of those figures were labeled, and the majority of the time, they did not match what any of the Egyptologists were saying. We were just wrong. We were just plain wrong. And I suspect if you were to find another one from a different place in Egypt at the same time period labeling them, that they’d have different labels, right? That they weren’t understood as the same people in the same way by everyone at the same time anyway. In the same way that if we were to look at, say, a pyramid on our dollar, right? What are the different ways people might interpret that symbol? As an Egyptologist, when I see a pyramid, I start thinking one thing. Someone who’s Masonic is going to think another thing. Someone who’s just an average student of U. S. history is going to think—and we’ll all interpret that pyramid in a slightly different way. And so that’s part of what we have to understand.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Kerry Muhlestein:

We also then have to understand maybe Joseph Smith is telling us what the average ancient Egyptian would have seen, but maybe not. He might have been telling us what a Jew in Egypt at the time, how he would have interpreted it. So I’ll come back to that. He may have been telling us how the priests who drew those particular papyri would have interpreted it. Or maybe he’s just telling us what we should get out of it, regardless of what anyone in the ancient world would have thought, right? So let’s talk about maybe Jews and priests for just a second to answer that question. And we can’t spend a whole hour on just this one question, but you’ll see how I geek out on this stuff. It’s just really fun, I think—really, really fun trying to figure this out and also to be able to admit these are the things we don’t know. I think good research has to say, “These things we can say are possibilities, and these are the things we don’t even know.” So there’s no doubt that people in the ancient world looked at each other’s languages, stories, and symbols and gave them their own twist and interpreted them in their own way. And so I’ll give you an example of this that I think all of our audience is familiar with, they just don’t know they are. There is a classical Egyptian story from around this, roughly around this time period of a powerful Egyptian magician who his father sees someone who’s poor and someone who’s wealthy and thinks that, you know, the poor guy feels so bad for him and the wealthy guy, he’s great, and his magician son, in order to teach him, takes him to the afterlife and shows him what happens to them and how really the poor man is doing well and the rich man isn’t and so on. And the way this is that the poor man’s with Osiris, right? The Savior retells that same story, only he calls it Lazarus and the rich man, and Lazarus is in Abraham’s bosom.

Scott Woodward:

Abraham’s bosom.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Right. He’s just taken an Egyptian story and reinterpreted it in a Jewish way.

Scott Woodward:

Wait, wait, wait. So you’re saying that Jesus did this, too?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Jesus, as a Jew, took an Egyptian story and instead of saying this was about Osiris, He said, he’s in Abraham’s bosom.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yes.

Scott Woodward:

So this is an example of Jesus doing this very thing.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Wow. That’s cool.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Now, did he encounter that in Egypt as a boy, or was that just a commonly known story, or did he hear it from someone else and he’s just repeating it, or what? I don’t know. But we certainly see it happening. And that’s the thing is a lot of times people are doing it without even realizing they’re doing it. That’s what we do with symbols, right? We impose our own reality and our own way of thinking onto whatever symbol we see. We can’t help but doing that. It’s what humans do.

Scott Woodward:

Wow. Interesting.

Kerry Muhlestein:

So another example we find from a later time period, but we find in Israel several synagogues that on the floor of the synagogue is a mosaic of a Greek zodiac. Now, we don’t know how they interpreted that, but what you can be sure is that if it’s in a Jewish synagogue, it was not interpreted the same way the Greeks interpreted it, right? Clearly, they are taking a Greek element of culture and giving it, you know, on one side of it it will have the story of Abraham sacrificing Isaac and on behind it it will have, you know, the throne of God or something like that, right? They are clearly incorporating this into Jewish ideas and thoughts and reinterpreting that symbol, so—and I would say that that Greek zodiac is very similar to the hypocephalus facsimile, too, in terms of their purpose and their intent and what they’re doing. And so if we know Jews are interpreting the Greek zodiac differently, then I would guess they’re interpreting hypocephali differently as well with the Jewish meaning, right? So there’s no doubt that Jews took these symbols and they didn’t say, “I’m going to take that and reinterpret this.” It just happened automatically. It’s just what you do, right?

Scott Woodward:

It’s just what you do.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. So I think that there’s a real possibility that we have a group of Jews who would see these drawings and just automatically assign a story they’re already familiar with to those drawings in the same way that they’ve done with the zodiacs in the synagogue or the story of Lazarus and the rich man.

Scott Woodward:

So do we have, like, other examples of Jews doing that kind of thing in Egypt around this time period, around 200 BC? Do we have other examples of them using Abraham or using Egyptian facsimiles or symbols to tell Abraham stories?

Kerry Muhlestein:

I think so. Some of them are—it’s a little bit hard to tell who is doing it. Is it an Egyptian or a Jew? So I’ll give you an example. Again, these are a bunch of stele that John Gee found. Sometimes they’ve got Egyptian, sometimes Aramaic, sometimes mixed stuff. Anyway, but there’s a scene that is typically thought of as—in fact, it’s very similar to Facsimile 3, where Osiris is on a throne. In these scenes, typically that’s how we’d interpret it. Osiris is on a throne, and someone is being brought to be in Osiris’s presence. But we find a number of these where what is labeled, instead of it being Osiris on the throne, it’s labeled as being Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and someone is being brought into Abraham’s presence, right? Which is very similar to what’s on Facsimile 3, the person on the throne is interpreted as Abraham, right? So is that an Egyptian who has adopted some Jewish perspectives, or is that a Jew who’s adopted an Egyptian drawing? I don’t know. And it may be some of both. I mean, there are plenty of examples of these, so there are all sorts of things we have to kind of think through as we approach it. So let me give you kind of the counterexample of that that your questions were also about. We know that there were priests in Thebes from around this time period—and this is a—the papyri that Joseph Smith had—so at least the original that Facsimile 1 is a facsimile of, was owned by a priest in Thebes from about 200 BC. So there are priests in Thebes from around that time period who we know were collecting stories from other religions. Now, that seems weird to us, because we’re monotheistic. But if you’re polytheistic, and you already worship 200 gods, and you meet, like, 70 more…

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Throw one more in the mix.

Scott Woodward:

What’s one more?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, it’s not what’s one more, it’s what’s the risk of not making them happy, of not using them, right?

Scott Woodward:

Oh, okay.

Kerry Muhlestein:

You want to make everyone happy, and you want to take advantage of everything you can, so it’s in your interest to incorporate all of the gods out there, all of the religious figures out there, and make them happy, so not make them mad, and use their abilities to your advantage. So we know that they were collecting stories of Abraham, of Jehovah, of Moses. They were using them in their spells. There’s absolutely no doubt that that was happening. We can demonstrate that. So is it possible that you have a priest who is syncretizing, is the word we use, who is mixing his ideas of Osiris and what he’s learned about Abraham and Jehovah and putting them together as a mash-up, that’s maybe the modern term for it, a mash-up, right? And he’s putting them together so that they mean both. He’s—with the same drawing, he’s invoking Osiris, he’s invoking Abraham and Jehovah and so on. And he intends to get the benefit that can come to him from appealing to all of these gods and all these religious figures. We know they were doing that in some way, so is it possible that’s what they’re doing with these drawings? So let me put it this way: I think it’s almost impossible that someone wasn’t doing it somewhere.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Like, it’s happening somewhere. So why should we look at these and not say, “This might be an example of that?” That would just be actually irresponsible. So I don’t know if that’s what’s happening here, but I think it’s quite possible.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, so Annie’s question was, are you saying it’s possible that a Jewish person took what Egyptians depicted and wrote their own story about Abraham? And you’re saying, absolutely.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, or maybe not wrote their own story, took a story they already had and saw it in that drawing.

Scott Woodward:

And saw it in that drawing. Okay, so there’s a story floating around about Abraham being sacrificed or nearly sacrificed by his father’s priest buddy, and they used that Facsimile 1 depiction to say, hey, that reminds me of that story.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. That’s what they saw in that story, in the same way that I’ll see something different in the pyramid on the dollar than you will. You just see what you’re expecting to see, and that’s what they’re expecting to see.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So one of the things we’re getting a feel for is this is less of an exact science than sometimes it’s played off as being, is that correct?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yes. In fact, I often say if someone is giving you a simple explanation for this, that’s when you should stop trusting them. If they’re saying, “It’s this way. It’s one to one. This is how it is,” they’re not telling the full story or they don’t know the full story. That’s all there is to it. This is complex stuff. From an Egyptological point of view, if there was nothing book of Abraham, still dealing with these texts and these documents, this would be complex stuff. And so don’t simplify. The problem is that saying, “Oh, all of this is so simple, and it’s this way” makes for an easy soundbite. The truth doesn’t make for an easy soundbite. You just have to be patient and work hard if you want to get towards the truth.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Embrace complexity, huh?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Can I push back a little bit on that, because doesn’t it seem like Joseph Smith’s explanations on the facsimiles are straightforward and simple? Doesn’t mean they’re not contested, but they are straightforward and simple, so how would you respond to that?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, I’d say he is giving us an explanation, and even then they’re complex—they’re not so straightforward, but—he’s giving us an explanation that is straightforward. So the complexity is, does that mean that’s the only way to interpret these?

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm. Okay.

Kerry Muhlestein:

So, it’s more complex than that. I would also say that there are a number of things that he says that seem to match up incredibly well with an Egyptological understanding and some things that don’t. And as I said, as Egyptologists, we don’t really understand these as well as we’d like to think we do, or as we would like to, and so, anyone who says his explanations don’t match what Egyptologists say is wrong. Anyone who says they completely match what Egyptologists say is wrong. The truth is that in some ways they do and in some ways they don’t and that’s true of every explanation I’ve heard of them from anyone.

Scott Woodward:

So it kind of depends on the Egyptologist.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, well, and on our limited understanding.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

We’ve got a question, then, about a specific thing. So I think this is a good way to address what you’ve been bringing up. This is from Kenneth in Murray, Utah. And he wrote, “I completely agree with your discussion of viewing the facsimiles within a cultural framework of appropriation and re-application.”

Kerry Muhlestein:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

“But what can we make of examples where Joseph directs the reader to specific hieroglyphics, such as his explanation of Numbers 2, 4, and 5 in Facsimile 3, which mention the characters above the figures’ heads or hands. This isn’t a picture being given additional layers of meaning but actual text that can be read and does not seem to match what Joseph suggests.” So how would you answer that question?

Kerry Muhlestein:

That, I think, is a great and perceptive and informed question. If you read my stuff or hear me talk very often, you’ll find all sorts of places where I say that I’m finding more and more answers to lots of things, and there are some things that I still am searching for answers for. And this is one of those that I have in my mind when I’m saying that. See, you’re right. Again, he doesn’t give us a translation of what they say, but it’s pretty close to that. He says, this is so and so, as can be seen in the hieroglyphs above their head or above their hand or whatever else, right? And those hieroglyphs are actually really hard to read. The problem is we’re not looking at the actual hieroglyphs. We’re looking at the ink imprint from a metal carving that may have come from a wood carving that was done by someone who didn’t understand hieroglyphs. So they’re pretty hard to read, and there’s not complete agreement on what they say, but even with the loosest way of looking at them, they don’t seem to say what Joseph Smith was indicating. So my question is, why would that be? And I don’t know the answers. I can make a guess, but it really is an informed guess, but it’s just a guess, all right? So is it possible that Joseph Smith is receiving inspiration either that this is how an ancient Jew would have interpreted those people, or it’s how one of these priests that may have interpreted those people as being more than one person, trying to draw as much meaning out of them as possible? Or that this is just how he was inspired, that we should understand the symbols so that we can get out of them what we should get out of them, which is what you do with symbols, right? So, that’s fine. Is it possible that he’s inspired to say, this is how we should understand that person, and then he just makes the assumption, and the hieroglyphs above them, because he can’t really read hieroglyphs, the hieroglyphs above them say that, and that God doesn’t disabuse him of that notion, just like he doesn’t disabuse most of us of most things. For example, like, he doesn’t disabuse Jacob’s assumption that Joseph is dead even though Jacob is a prophet, right? He doesn’t disabuse Joseph of this. Is that possible? Yeah, I think that’s very, very possible. Is that the explanation? I have no idea, right? This is one of those things that is just going to take some more research and maybe just some time, and maybe it’s like millennium amount of time. I don’t know. I always like to think we might figure out something before then, but I’m aware that there are many things we won’t. So I don’t know what the answer to that is. I believe that there are all sorts of possible explanations, but I don’t know.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, and then the biggest criticisms, of course, come to Joseph Smith about things like that, right? It’s almost like, Joseph, you claim to be able to translate, and now we actually have a way to test your ability to translate, and it doesn’t seem like you’re getting it right.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And what I’m hearing you say is there’s assumptions loaded in that very accusation, correct?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Exactly right. Exactly right. And we need to remember that while Joseph is inspired in the translations he gives us of scripture and so on, it doesn’t mean he’s inspired in every single thing he says about these things. I think it’s also worth understanding that we can look at a lot of things that Joseph Smith got so right that you’d say, “There’s no way he could get that right.” So I’ll just give you a couple of examples. His explanations of Facsimile 2 about, this is about the temple and this is about the temple, when we translate them, they’re about creation. They’re about having eternal increase, you know, children for forever, progeny for forever, they’re about being holy in the afterlife. They are the things that are in the temple, right? Are those just good guesses Joseph Smith made? Or I’ll just give you another example: He uses the word shinehah and points it towards the sun. And we can find that exact word used during Abraham’s lifetime, speaking of the sun and its path. So, I mean, making up a word that happens to be the right word for the right time period, The chances of that are fairly astronomically small. So how do we square those things? Okay, some things that you would think there’s no way he could get right, he gets right, and then he says that about these glyphs, and from our point of view, they’re wrong. How do you square those things? Well, that’s difficult. And I think that here’s another thing that I would—have said before, and I would suggest again: When we are trying to figure out the process of someone dealing with the divine, we should not be surprised if there are a lot of things we don’t understand because we’re dealing with the divine. If I could understand everything about God and how He worked with us, that would actually be fairly disappointing to me, because it would imply God is not a lot different than we are. But I believe He is a lot different, and a lot of what He does and a lot of the way we work with Him is not easy for us to understand, and we’re just going to have to kind of wait a while to figure it out. So I would say at that point, if we’re going to look at some things, that it’s clear, like how could Joseph Smith ever have been so lucky as to guess those things? But how could he have gotten this wrong? At this point, it requires at least as much faith to say he’s not inspired, as it does to say he is inspired. You’re just going to have to exercise some faith and selectively ignore things one way or the other.

Scott Woodward:

Because there’s so many things he got right, you’re saying you’d have to make a choice to ignore that.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. So if you’re going to be disturbed by his saying, okay, the glyphs over this hand say this, and we look at them and they don’t, then why are you not disturbed in the other way when you say shinehah really does mean what he says it means, and these things about the temple really are very temple-like texts, and so on and so—or when he says that these four figures represent the four quarters of the earth, and we’ve found Egyptologically they do.

Scott Woodward:

That should be disturbing to doubters.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Either way, it’s a religious choice and a faith choice one way or the other. You have to make the faith choice he’s not inspired or the faith choice he is inspired. Those are your two choices. There’s nothing—you know, it’s a faith choice either way. So if you’ve chosen he’s not inspired, how do you deal with those things? If you’ve chosen he is inspired, how do you deal with the other thing?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Kerry Muhlestein:

And the answer really is, we don’t know how to deal with those things. That’s not surprising. So I would say read the text and find out if the text itself is inspired.

Scott Woodward:

Well, dang it, Kerry, we were trying to get some certainty out of you today.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, good luck.

Scott Woodward:

All I’m hearing is this is complex.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Wow. I think that’s actually super good. So there’s room for doubt on both sides, but there’s also room for conviction on both sides.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And you’re saying that we need to settle this by going to the text itself, reading it, and trying to gain a witness the way that the Gospel Topics essay concludes.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. That’s exactly right. You’re going to have to exercise faith for whichever conclusion you make.

Scott Woodward:

Wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, Kerry, you mentioned some temple themes.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That lines up with another question. This is from Cade in Spanish Fork. He wrote, “The Book of Abraham and Joseph Smith’s description of the facsimiles seem to have many temple themes. Have those temple themes or others been discovered in other Egyptian writings or culture? So what about the temple and its link to this?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, so there are all sorts of temple themes in the text of the Book of Abraham and in the drawings. And, yeah, we find them all over in Egyptian culture. I mean, I’ve spoken about this before. Others have spoken about it. You can find in various publications, including one that should be coming out soon, on the Temple at Mount Zion conference from 2018, but there are a lot of connections between LDS temples—which, again, you find represented in many ways in the facsimile and in the text of the book of Abraham. There are a lot of connections between LDS temples and Egyptian temples. I’m writing a book right now on comparing ancient and modern temples, and one whole chapter will be the parallels between Egyptian temples and LDS temples. So, yeah, you find it all over the place. In fact, one of the things that I found interesting: When I spoke earlier about that lecture by Dr. Antonio Loprieno that made me decide to go study with him at UCLA, was he was talking about Egyptian religion, and I sat there thinking, “He’s talking about the temple.” Like, if I hadn’t known he was not a member of the church, I would have thought this was a member of the church highlighting similarities between LDS temples and Egyptian religion. He had no idea what we did in LDS temples—no idea at all. He was just talking about Egyptian religion, but it’s that clear. And I would also say that actually Dr. Robert Ritner, who has seen a lot of temple connections between the drawings on the facsimiles and LDS Temple texts and so on, has actually done a lot to help me understand this, probably more than any other person has helped me understand the connections between what we’re seeing in LDS temples and the facsimiles and the text of the book of Abraham and has really strengthened my understanding of that.

Scott Woodward:

Another listener named Paul from England highlights Hugh Nibley on this. He said that Hugh Nibley claimed that the Egyptians coveted the priesthood and temple from the earliest times and their temple rites were an attempt to emulate the true ordinances, thus their obsession with keeping the body whole for resurrection, etc. And there’s also temple rites involving gatekeepers and passwords and signs as essential passages.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, which is what Dr. Lopriano was speaking about when I went to that lecture.

Scott Woodward:

Really?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Okay. So your research has confirmed that idea?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, yes and no. So certainly there are a lot of parallels, and so the question we have to ask ourselves is, “How did those parallels get there?” And we don’t know the full answer. There are several possibilities, and my guess is it’s a little bit of all of those. So the idea that they are imitating true temple ordinances and rituals from the earliest days, that idea comes from a text in the book of Abraham where it talks about Pharaoh, who’s a good man, and wants to have the rights of the priesthood, but he can’t have it, so he imitates it. So that’s a possibility. It’s also—we know as members of the Church that the Abrahamic Covenant and rituals have been around since Adam down to Noah, and at one point everyone knew about these. So we should expect to see corrupted echoes of true rituals not just in Egyptian culture, but in every ancient culture. I mean, we should expect to see that, because they all came from an original source, and so that’s one reason why we may see some of these parallels. In general mankind wants to interact with the heavens, and temples and rituals help us do that, so there should be some commonalities. There’s also another interesting thing: We know that the Masons were intentionally borrowing from Egyptian symbolism, and we know that Joseph Smith, when he was trying to figure out—he had the theology and the inspiration of what the endowment and temple rituals were supposed to be like, but as he’s trying to find ways to actually put that into action, he was influenced by the Masons. So there’s probably an indirect reason also for some similarities with Egyptian temples, and my guess would be that all of those, everything I just said, in one way or another, impacts what’s going on. So again, it’s complex. See how this works?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, there it is again. There it is again.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And Casey mentioned, I guess two episodes ago now, he mentioned that the temporal parallels between when Joseph is rolling out the temple endowment in May of 1842 corresponds pretty tightly with the same time when he is rolling out the publishing of the book of Abraham in the Times and Seasons.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

There does seem to be even a direct correlation there, at least temporally.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Absolutely. And in 1835 as well. It’s right after he starts translating the book of Abraham in 1835, then in early 1836 he starts to do the first temple ordinances, which are some washings and anointings and so on, even before the temple’s finished. So what you can see is that every time he works on the book of Abraham, new temple rituals come forward, so. I’ve written about that. Dick Bennett has written about that. I mean, it’s becoming pretty clear that the Book of Abraham gets Joseph thinking about the temple, and I think it opens him up to inspiration to receive what God is trying to give him to move forward in temple rituals.

Scott Woodward:

So is that how you’d frame it? You’d say it’s not so much that he’s getting the temple rituals from the Book of Abraham or from the facsimiles, but that is acting as an occasion for meditation, as a springboard for additional revelation for the temple liturgy that we have today?

Kerry Muhlestein:

I just don’t know. I think both are possible, and maybe it’s some of both, but we’ll have to wait until God and Joseph Smith tell us to know the answer to that question, so.

Scott Woodward:

What’s your hypothesis, Kerry?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Probably some of both, but largely the latter. It acts as a springboard to revelation. Like, it opens his mind and gets him pondering deep and solemn thoughts that allows the Spirit to reveal things to him. That would be my guess, but frankly, I have no idea.

Scott Woodward:

Good. No, that’s good.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Now, Kerry, you mentioned Robert Ritner as someone who’s helped you, but we had a couple readers point out that Dr. Ritner has also critiqued your work a little bit. Several podcasts he’s appeared, he’s spoken about some of that.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Could we give you an opportunity to maybe answer some of those critiques?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. So Dr. Ritner has been probably the most vocal Egyptological critic about the book of Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Kerry Muhlestein:

But Dr. Ritner put some time into studying at least the Egyptian texts and the drawings and really trying to understand them. So he and I interacted a number of times about this issue, and we had fairly positive interactions. He has had interactions with other LDS Egyptologists that have been fairly negative and so on, but he and I had largely positive interactions. I can’t think of any that were negative other than in print disagreeing with each other a little bit, but even that I thought was not out of the ordinary in what happens in Egyptology. It happens all the time in academia, just in general, right? So I would say a couple of things about that. One, I think our first kind of published thing with this, and I think this addresses a question you had, someone had as well, when he published a translation of the fragments of the Joseph Smith papyri, Fragments 1, 10, and 11, that we call the Book of Breathings. The Facsimile 1, the original of Facsimile 1, was on that group of fragments. He translated that and published it at about the same time that an LDS Egyptologist named Michael Rhodes did that. And so I did a little review of Rhodes’s book. And as part of it, I just went through and looked at all the places where their translations significantly differed and said, “Okay, well, here’s the difference, and as you look at it carefully, I think Rhodes is probably right in this case and Ritner is probably right in this case, and in some of these cases, actually, this text is so broken, you can’t tell.” And I feel like Ritner took that fairly well. He was a good Egyptologist. He really didn’t like anyone disagreeing with him, and that’s true of most academics, so he took that fairly well. There were a couple places where he said, “No, I think it’s this way.” And on one or two he convinced me, and on most I think he didn’t convince me at all. But I will maybe use that to highlight what might be an essential difference between the way he and I approached a lot of these things. There was one place where it was a number that was being written, but the text was faded and broken a little bit there, and so he had put down one number, and Rhodes had put down another number, and I went in and explained why you could take both of those, and that there just wasn’t enough evidence to determine that we really couldn’t tell which number it was. And in his response to that, He said, you know, well, it’s this number, Rhodes said it was this number, and Muhlestein just couldn’t decide, right? Well, the fact of the matter is there wasn’t enough data to decide, but many people feel like, well, you have to make a decision one way or the other, whereas my preference is to be transparent and say, actually, no, you can’t decide. There’s not enough data to decide. I’ll say two other things about Dr. Ritner. Like, I think he helped me understand the book of Abraham more than almost any other Egyptologist. Maybe the exceptions are a couple of LDS Egyptologists who’ve helped me understand it as much, but he helped me understand it a lot, and in my view, most of what he said from an Egyptological point of view actually really supported and helped flesh out an understanding of the book of Abraham and the facsimiles and so on from Joseph Smith’s point of view. In fact, I end up citing him quite a bit whenever I talk about these things because he did a lot of things that really helped us understand it. The difficulty is he was very good in most of his Egyptological work on that. I mean, there were some problems with some assumptions that he made about lack of historicity and anti-religious biases he brought with him and so on, but most of it was pretty good. What he wasn’t very good at, and I can’t blame him for this—it wasn’t his realm—was the church history side. And he just relied on other people for that, and he relied on other people who had made some bad assumptions. So the problem is that most of the time he’d take this Egyptological stuff that he understood and apply it to the book of Abraham in a way that didn’t work, because he was coming in with wrong assumptions and incorrect historical ideas. And so the Egyptology is usually pretty good. The application of it was usually not that good.

Scott Woodward:

Do you have any concrete examples of him doing that that maybe our listeners could grab on to?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. Most of it would come back to the things we’ve already talked about. He had assumptions that what Joseph Smith was translating was the text on the papyrus that was around the drawing that Facsimile 1 is a facsimile of. He made assumptions that Joseph Smith was telling us what the average ancient Egyptian would have seen in these drawings, and he made assumptions that we understood those drawings really well from how Egyptians would have seen it from that time period. And all of those are incorrect assumptions. I, again, I’m not going to blame him for the first two of those because he was relying on some historians who had made those assumptions, and he didn’t recognize that they’d made those assumptions, so that just hampered his ability to apply his understanding of the ancient world to what was going on in a more modern world.

Scott Woodward:

Gotcha.

Kerry Muhlestein:

That’s where things fell apart was the transition from one to the other, because he was going into an area that he hadn’t really studied and didn’t really know everything that was going on and was relying on other people, and that happens when we branch out beyond our specialties and we rely on people. That’s just going to happen, and I don’t blame him for that, and I’m not upset about that, but I do think that people should be aware and be careful. I will also say that towards the end of his life, he did a whole bunch of long interviews on some different podcasts. And even he—or I can’t remember if it was him or the host of these podcasts—invited me to come on and then debate him on there. The problem is that the hosts have a distinct, sometimes cantankerous and anti-LDS bias, and I just didn’t picture how we would actually have a reasonable debate that would really get towards the truth rather than just being kind of mudslinging and a bunch of other things like that, and I just don’t like that. I like to have real conversations where we can debate the issues in a real way. And typically in academia, we recognize that that doesn’t happen so well in a setting like that, and so we try and do good, careful studies where you have some time to think it through, present it. You send it through academic referees who say, yes, this works, this doesn’t, and so on, and you get a bunch of points of view. So I emailed him and invited him to do that. I said, why don’t we put together a book? Let’s just have the rules be you don’t attack the person, you talk about the issues. You can write an article about this and this and this issue. I’ll write an article. We’ll ask John Gee to write something. We’ll get a neutral editor to edit it and get blind referees to go through it all and so on, and so I invited him to do that. His health was starting to fail, and he said, I just, I don’t think I can do that. I don’t have the time for that. And I said, well, then what are some other ways that we can approach this? How can we have a good, responsible academic debate? And I even offered to fly out, now this was at the end of 2020, and meet with him in Chicago to sit down and discuss, how could we move forward in a responsible way to have a good, realistic academic debate? And he told me that he wasn’t so sure that would work well. And I emailed him back, and I said, I would love to hear your ideas. How can we do this? I don’t want to get into a mudslinging podcast fest. I would like to really have an honest dialogue with you about this. And he never did reply to that. And I suspect—I mean, his health really was failing, and he passed away not too long after that. So I suspect that that’s why, or at least I’m going to assume that that’s why, and I regret that we got to this so late in his life that we weren’t able to put that together, because I think when he felt—and this is true not just of Dr. Ritner but of all of us—when he felt attacked, it was hard to get to the real dialogue, but when—my experience with him was that when you could calmly talk that he could have really good academic debates, and I would have liked to have done that with him, and I regret that we started approaching it when he just had too much else going on to have made that happen, but I did my best to make it happen, and it just didn’t work out.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Dr. Ritner passed away in 2021, as you noted, and we appreciate the way you’ve handled this, too. You’re a classy guy. It’s too bad that that debate didn’t get to happen.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. And I’m not trying to disparage him in any way. I haven’t been trying to say that his personality or his scholarship or anything else was faulty. If it came across that way, I certainly didn’t mean that. I think he was a typical academic, where we disagree with each other and sometimes that bothers us, but he had great capabilities, and we had some great dialogues with each other, and I always appreciated that.

Scott Woodward:

Here’s another listener’s question along those lines: This is Soren from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Soren says, “Dr. Cooney of UCLA and Dr. Ritner of the University of Chicago commented on the lion couch scene talked about by Dr. Muhlestein and on an episode of your podcast. They both state that the name Abraham has nothing to do with the couch or the lion.” Okay, this is a reference to the Leiden papyrus, right? This is the Leiden papyrus. Underneath it there’s that Greek writing, and one of the words there is “Abraham.” And so Soren goes on: he says, “They said that it appears in a list of biblical names and is completely unassociated with the picture. They say that it is just one of the many names listed as a part of a Coptic magic spell. Dr. Muhlestein, could you respond to this specific objection?”

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. I’m very, very happy to do that and welcome this opportunity to correct myself in one case, and I have done so in an article as well. So let me say this, that that papyrus is written with a kind of a mixture of text and language script and so on that is beyond my specialty or Dr. Cooney’s specialty. It was in Dr. Ritner’s specialty, and it’s in Dr. Gee’s specialty. And so I at one point published because I misunderstood something that Dr. Gee had both written and said to me in person, and so I once published that the text said that it was Abraham upon the altar. And I was corrected in that, and I’ve corrected that in print, that that’s not what it said. So if I am understanding correctly now, and we’ll have to ask Dr. Gee this, because it goes beyond my specialty, but it is squarely in his specialty, and he’s spent a lot of time with that text. So there is a part of the papyrus where there’s—and I can read much of this, that there are lists of names and all sorts of things going on. But that mention of the name Abraham, my understanding is that the text says that this text is associated with that drawing, which is important because often texts and drawings that are adjacent to each other aren’t necessarily associated with each other. So my understanding is that the text itself says that this text goes with this drawing, but I will have to defer to Dr. Gee to handle that more carefully because that text goes beyond my specialty.

Scott Woodward:

Sure. So is it fair to say, though, that the significance of that association, of having the name Abraham near a picture of somebody on a lion couch scene on a papyrus that comes from Thebes in the right time.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, it’s from a later time period.

Scott Woodward:

Was it a later time period? Okay.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But it is from Thebes.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, and it’s not, like, a ton later, but a bit later.

Scott Woodward:

Okay. But it is showing us that Abraham’s name is being associated with the lion couch scene. I mean, can we say it like that, in some way?

Kerry Muhlestein:

In some way, yes. And if I’m understanding Dr. Gee correctly, Abraham’s name is very straightforwardly and closely associated with the lion couch scene. If I’m understanding that incorrectly, it’s still at least in some way associated with it. So, again, we actually have examples of all three facsimiles being associated with Abraham by Egyptians in some way. So, again, that’s not what’s going to prove or disprove any of this, but it does highlight that anyone who is telling us that there’s no way that any of what Joseph is saying about the explanations is correct and that Egyptologists would say it’s all—again, they’re just simplifying and that’s just incorrect information, and so we just need to broaden our minds a little bit on that.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. And the fact that Abraham was associated with facsimile 1, 2, and 3 in Egypt outside of what Joseph Smith has said does increase the plausibility of Joseph Smith’s claim, doesn’t it?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Oh, in a huge way. In fact, I sat down one time with a mathematician and I said, okay, I don’t think that 25 percent of drawings are associated with—in ancient Egypt—are associated with Abraham. It’s not even close to that. But let’s assume there were 25 percent were. What are the odds that you have three drawings, and you say that all three are, when only 25 percent are, but in this case all three are. What are the odds? And the odds were, like, so small you should go play Powerball instead. And so, again, I’m not saying that statistically now we’ve proven that Joseph Smith is a prophet, but it certainly is statistically plausible and just downright intellectually dishonest to say none of these things Joseph Smith said about the facsimiles work Egyptologically. And I’m not sure that Egyptologically is where we should be looking, as we talked about earlier, but it’s just not accurate to say that it’s not possible. There are plenty of things about it that are.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Kerry, maybe I can ask a question that takes us off in a different direction, but Scott and I had talked about this. This is a question we definitely wanted to ask. It’s from Rory, who’s in San Antonio, Texas. And he wrote, “It seems that the book of Abraham and other canonized scriptures, depend on much of the Old Testament being literal, such as Adam and Eve, the Tower of Babel, Abraham, Moses’ exodus, so on and so forth. I found that many biblical scholars do not believe these stories to be literal.” And then he wrote, “How can I reconcile the early church’s truth being contingent upon these stories being literal?”

Kerry Muhlestein:

So I don’t know that it is contingent upon them being literal. And I would again say that it’s more complex than we are admitting, right? So everyone who says that none of these things could be literal or are literal is simplifying. Anyone who says they are all literal for sure is simplifying. There’s probably a mix somewhere in between those two. And so let me put it this way: Maybe let’s just talk about the creation story. If God wants to give us an account of the creation story, I think he could give us a geological account of the creation story. He could give us an astronomical account of the creation story. He could give us a quantum mechanics account of the creation story, a nuclear account of the creation. He could do all those things.

Scott Woodward:

Sure.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Instead he gives us an account that teaches us what he wants us to know. And some of that may be conveyed through symbolism because symbolism is a language. It really is a language. And so he may have created symbols that teach us what he wants us to know. I would say probably the biggest answer to that is if we were to go to the book of Moses, where Moses asks, how are these things created? And again, rather than giving a quantum mechanics or even a Big Bang answer or something like that, he says, by the power of my only begotten son, right? That’s the part that he wanted to make sure that we knew. That’s the part that’s most relevant for us. So if he does some of this teaching through some symbolism, then fantastic. Although I think that it’s actually naive and simplistic to just reject as many of the things that people say that can’t be literal. I think that often rejecting that is also naive and simplistic, as are many of the theories—so, again, I work in the biblical world as well, and many of the theories about the text of the Bible and when it’s created and so on are just so incredibly simplistic. There’s no way it could be that simple and that easy, but the human mind wants to go simple and kind of runs away from the complex. So, too often we go with that simplistic explanation that either it is A or B, right? And that’s just not going to work.

Scott Woodward:

So there could be some stories in the Bible that could be symbolic or metaphorical or the people were real, maybe we’d say loosely based on true events, but there’s some artistic interpretation that occurs in the story to make certain points, and that that’s totally okay, that’s totally fine. The book of Abraham is not contingent upon whether or not people are doing that kind of thing.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Okay, Kerry, let me ask another question. There’s actually a few questions sent in. We have Julie from London, England. We’ve got Josh from Visalia, California. I think I’m saying that right, Josh?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Visalia.

Scott Woodward:

Visalia. Okay, thank you.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Mm-hmm. Used to live around there.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, okay. And then Paul from England. They all bring up Hugh Nibley. Maybe I’ll just have Josh ask it, he says it maybe the most concisely. He says, “How relevant are Dr. Hugh Nibley’s books on the book of Abraham?” He said, “I’ve read these books as a young adult, but I haven’t heard any references or similar conclusions from them during your series or in Dr. Muhlestein’s books. Has new, more complete information come forward that makes his works less relevant or even disproven?” What do you want to say about Hugh Nibley’s work on the book of Abraham?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Well, there’s so much of it. It’s hard to give, like, one answer to that. We’d have to go through a whole lot of things to really answer it. So let me put it this way: So much of it is still very, very relevant. There are certainly things that we’ve come to understand more, like we’ve come to understand, okay, well, maybe this actually works in this time period but not that time period, and so on and so on. But maybe I’ll just put it this way in a larger perspective about Dr. Nibley, on whose shoulders all of us stand. Anyone who’s researching anything about the ancient world from an LDS perspective right now is in some way standing on Dr. Nibley’s shoulders, and he just did incredible stuff. I think he also was very, very inspired quite often, and as someone who was inspired, he saw connections that I think were probably valid connections, but he saw them and he made them sometimes in ways that we cannot right now academically support. So he tied together things from different time periods and different cultures that probably really are interrelated and somehow, but right now we have to say, okay, wait, how would that culture have influenced this culture from that time period in a different time period? And we can’t demonstrate how it would have happened. It doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. And I suspect that we’ll find that 99 percent of the time he was right. That may be only 93.3. I don’t know. But methodologically, right now, we can’t do it, so—and some of this is because his brain was so good at seeing connections that he saw stuff that probably he actually could back up and he just didn’t take the time to do it, and none of the rest of us can see it. And some of it is doing things that were just, like, you can’t do that, even though it’s probably right, because we can’t show that it’s right. But he still has great, great stuff. I think it’s worth reading. And then, you know, some of it is outdated, but most of it’s still very relevant, especially the idea.

Scott Woodward:

Sure, sure.

Kerry Muhlestein:

He was an idea maker and capturer, and that stuff is great.

Scott Woodward:

Love it. Here’s a question from John from Provo, Utah. He said, “In your episode on the Abraham facsimiles, you brought up some proofs of the book of Abraham, like Olishem. As a non-specialist, it can be hard to discern which proofs might only be acceptable to Latter-day Saint scholars and which ones are genuinely accepted by Egyptian scholars who are not church members. Could you please share the top three most solid intellectual evidences for the book of Abraham having ancient connections that Joseph Smith could not have known of?” That’s a good question.

Kerry Muhlestein:

I don’t know if I could say which are the top three, but maybe let me just address that idea in general. I wouldn’t say that any of these are proofs, because I don’t think we’re going to prove this in this method. I think that the proof will have to come through revelation, honestly. I just think it’s been set up that way.

Scott Woodward:

Can we call them plausibility enhancers?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, okay. Let’s call them that. Plausibility enhancers.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Kerry Muhlestein:

So let’s use Olishem as an example. So Olishem is a name that is used in the text of the book of Abraham about some plains that are near where Abraham is at the beginning of the story and Ur and so on. Now, again, let’s embrace some complexity. There are some questions about where is Ur, who are the Chaldeans? And the simple answer is people will say, well, Ur of the Chaldeans, those are Babylonians, and it’s down in Southern Iraq, and they’ll just go with that. Well, it’s not that simple. First of all, we know that the Chaldeans didn’t originate there, that the earliest that we find them is up in, like, north and west of there, so say in the, like, Syria, Turkey area. That’s where we’re kind of finding linguistic evidence for them. So if we were going to start looking for places around there, there are several places that are named Ur around there, so we could posit a northern Ur. That’s not what most people think, but again, they don’t have the book of Abraham as evidence and lots of other things, so anyway, it turns out that as we look at some ancient texts, that there is a place called Ulisum right around one of those Urs in kind of the modern Turkey near the Syria border area. So that seems quite striking, and especially when you look at things from a linguistic point of view. So, S’s and SH’s—so the S-SH shift happens all the time. You can even see evidence for it in the Bible. So, for example, there’s a time where they’re trying to figure out if people are from one tribe or another, and they ask them to say Shibboleth, because people from the wrong tribe only can say Sibboleth. They can’t say SH. That sound shifts all the time. That’s known. Oo’s and Oh’s shift all the time as you go from one language to another. So Ulisum and Olishem are, like, perfect linguistic matches. It’s from the right time period, all sorts of things. So what I think we can say is that there is definitely a place in the area that many of us would posit Abraham was from. That was called Ulisum or Olishem. There’s absolutely a place, I think there’s no doubt that there’s a place like that. Does that prove it? I don’t think it proves anything, but it sure makes it believable. It’s sure impressive.

Scott Woodward:

What are the odds that Joseph Smith could have known about that?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah, that he could make up a name that is in the right place at the right time period. Again, right? You should really be playing a lot of Powerball if you believe that he can guess that well.

Scott Woodward:

Best guesser in the history of the world.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. Joseph Smith is, from many people’s point of view, the luckiest guesser that ever lived. Again, it just takes a lot of faith to discount these things. But there are other things it takes faith to believe in, right? That’s the nature of how this works. I think it’s intentionally set up that way by God, that it will take some faith.

Scott Woodward:

No slam dunks on either side.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah. Some of the other ones, I’ve already mentioned the shinehah one, which in some ways is just mind-blowing to me.

Scott Woodward:

So the shinehah one is the right word in the right time describing the path of the sun across the sky. And that’s not a word that was used later, right?

Kerry Muhlestein: