Revelations and Translations |

Episode 7

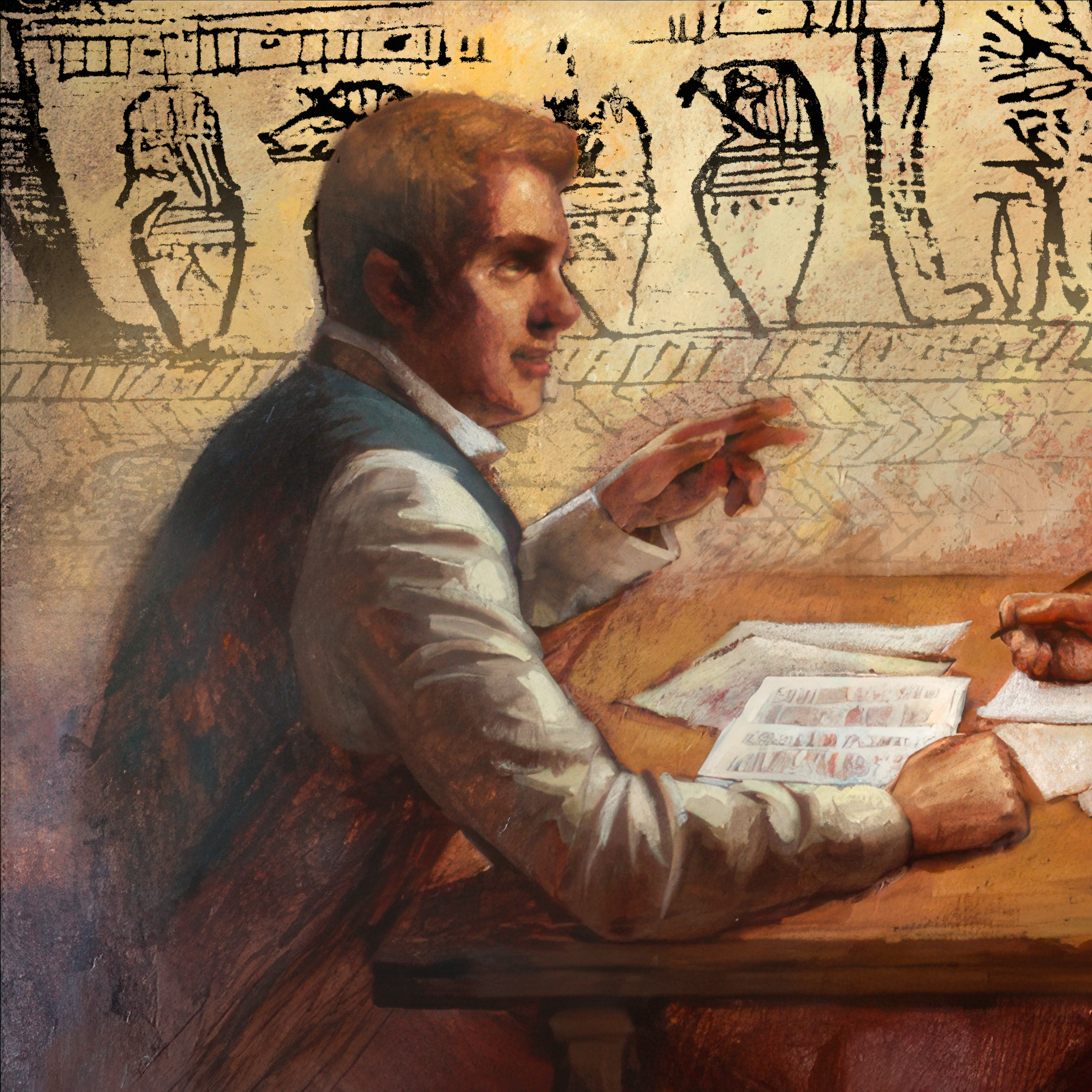

The Book of Abraham: Origins and Controversies

56 min

The Book of Abraham, Joseph Smith’s final translation project, is easily one of the most controversial books of scripture in the Latter-day Saint canon, and we want to talk about it. In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we dig into the fascinating story of how the exploits of a 19th-century grave robber in Egypt ended up expanding our scriptural canon. We look at where in Egypt the papyri from which the Book of Abraham was purportedly translated came from, and how Joseph Smith came to possess both this papyri and a couple pair of mummies. We look at the three theories of what source material Joseph Smith translated from and how he did it, and we trace what we know of what happened to the papyri after Joseph’s death, how many fragments have survived to this day, and what modern Egyptologists think about those surviving fragments, which is the source of the two biggest controversies about the Book of Abraham.

Revelations and Translations |

- Show Notes

- Transcript

Key Takeaways

- The Book of Abraham is unique scripture that highlights Abraham’s witness of Jesus Christ, provides details on God’s covenant with Abraham, contains teachings on the premortal nature of humanity, presents a unique account of the Earth’s creation involving a larger number of beings than previously known, and adds depth to the story and background of Abraham. Despite being a short book, it offers significant insights and teachings, making it valuable to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- An era of Egyptian antiquity interest in Europe, sparked by Napoleon Bonaparte’s exploration in Egypt in 1798, led to the discovery and collection of mummies and papyrus scrolls. Antonio Lebolo, an Italian explorer and antiquities dealer, discovered a cache of mummies and papyri in Thebes, Egypt, between 1817 and 1821.

- After Lebolo’s death, Michael Chandler acquired the mummies and papyri that had been in Lebolo’s possession and took them on a circuit tour in the United States. Later, as interest in the artifacts waned, he began selling them off. In Kirtland, Ohio in 1835, with funds raised by Church members, Joseph Smith purchased two scrolls, several papyri fragments, and four mummies from Chandler. Eyewitness accounts describe the scrolls as a long roll and a shorter roll (both sometimes described as being in a state of perfect preservation) and the fragments as deteriorating. The Book of Abraham was written after the acquisition of these papyri.

- After Joseph Smith’s death, the mummies and papyri went through various hands. They went from Lucy Mack Smith to Emma Smith, and then to Abel Combs, where they were divided: Combs gave two of the mummies and most of the papyri to a museum in St. Louis and kept fragments of the papyri.

- The articles given to the museum in St. Louis were then moved to the Wood Museum in Chicago, Illinois where they were destroyed during the Great Chicago Fire. The fragments Combs kept, however, were passed after his death to Charlotte Benecke Weaver, who gave them to her daughter, Alice Heusser. After Alice died, her husband sold the fragments to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1946. In 1967 the Church acquired these fragments from the museum. These are the only extant portions of the Joseph Smith papyri that we have today.

- There are three theories as to how the Book of Abraham came to be:

-

- Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham from the papyrus fragments that we have today.

- Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham from the long scroll, which has since been destroyed.

- The physical papyri served as a catalyst for Joseph Smith to receive revelations about the life of Abraham. Similar to his translation of the Book of Mormon and the Bible, Joseph claimed to receive these translations through direct inspiration rather than traditional language translation skills.

- Theory 1 is widely considered unlikely due to the lack of correlation between the fragments and the Book of Abraham. Both Latter-day Saint and non-Latter-day Saint Egyptologists agree that the papyrus fragments, though they contain one of the facsimiles published with the Book of Abraham, contain no text related to the story of Abraham.

- Theory 2 seems more likely. Eyewitness accounts of the translation assert that Joseph was working from one of the scrolls during the translation process, usually the long scroll. Theory 3 is also a strong possibility since those close to Joseph at the time recorded that he claimed to be receiving the text of the Book of Abraham translation by revelation.

Related Resources

Gospel Topics essay, “Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham.” churchofjesuschrist.org.

Muhlestein, Kerry, Let’s Talk about the Book of Abraham. Deseret Book, 2022.

Gee, John, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, Deseret Book, 2017.

Pearl of Great Price Central website

Joseph Smith Papers, “Introduction to Egyptian Papyri, circa 300-100 BC,” (with images of papyri fragments) josephsmithpapers.org.

Joseph Smith Papers, Egyptian Papyri, josephsmithpapers.org.

Joseph Smith Papers, “Miscellaneous Papyrus Scraps, circa 300–100 BC,” josephsmithpapers.org.

Scott Woodward:

The Book of Abraham, Joseph Smith’s final translation project, is easily one of the most controversial books of scripture in the Latter-day Saint canon, and we want to talk about it. In today’s episode of Church History Matters, we dig into the fascinating story of how the exploits of a 19th-century grave robber in Egypt ended up expanding our scriptural canon. We look at where in Egypt the papyri from which the Book of Abraham was purportedly translated came from, and how Joseph Smith came to possess both this papyri and a couple pair of mummies. We look at the three theories of what source material Joseph Smith translated from and how he did it, and we trace what we know of what happened to the papyri after Joseph’s death, how many fragments have survived to this day, and what modern Egyptologists think about those surviving fragments, which is the source of the two biggest controversies about the Book of Abraham. I’m Scott Woodward, and my co-host is Casey Griffiths, and today we dive into our seventh episode in this series dealing with Joseph Smith’s non-Book-of-Mormon translations and revelations. Hello, Casey Griffiths.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Hello, Scott. How are you doing?

Scott Woodward:

Just great. How you doing?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I’m doing great, and I am excited to talk about our subject today because this is complex, but it also—it has a connection for me going back to my youth.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I remember sitting in sacrament meeting and flipping through your scriptures. There’s no smartphones back then. And for some reason I would always go to the Book of Abraham And can you guess the reason why I’d go to the Book of Abraham?

Scott Woodward:

Same reason every kid goes to the Book of Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

It’s the only book of scripture that has pictures.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yep. Yep. And so, you know, it was—I’m a visual person, and so I remember looking at Facsimile 1 and then going to Facsimile 2 and being like, “Whoa, what the heck is this doing in here?” and just having a connection with it because of that. So if you’re a visual person, you’ve probably had the same experience where you’re flipping through your scriptures and the Book of Abraham jumps out at you.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. It’s all we had as kids.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, yeah. My kids are playing Candy Crush and Barbie’s Dream House and everything like that, and meanwhile, I’m pondering Facsimile 2, because that’s what we had.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, yeah. Facsimile 2 particularly captured a kid’s attention, because you could spin it 360 in the pictures. You know, there’s some that are upside down, and it’s like a panoramic, 360 experience, you know?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Very cool. And as I grew and became more involved in the scriptures, I grew to really appreciate the Book of Abraham. It’s short, but it has a lot of powerful stuff in it.

Scott Woodward:

Little book, but packs a big punch.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah, it’s full of good stuff, and we’re going to spend some time today talking about the controversy surrounding the Book of Abraham, but we don’t want the controversies to overwhelm why this is such an important book of scripture. So, Scott, what are some of the big reasons why the Book of Abraham is important to Latter-day Saints, why we’ve canonized it, why we’ve kept it in the canon? What are some of the big teachings in the Book of Abraham?

Scott Woodward:

So a few things it does is there’s a lot of traditions—Christianity, Judaism, and Islam all claim Abraham, right? We love Abraham. Our traditions are called the Abrahamic traditions, all based on Abraham. We claim him. We love him.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

The Book of Abraham actually shows Abraham as an early witness of Jesus Christ, of Jehovah. And that’s an important thing that’s not as clear in the Bible. Another thing it does is add significant detail to the promises of God’s crucial covenant with Abraham that is outlined in the Book of Genesis, but there’s details in the Book of Abraham, especially chapter 2, that we don’t get anywhere else. It provides some of the most valuable teachings in our canon on the premortal nature of humanity, and there’s a little bit in there about the selection of Jesus Christ as our Savior. And that’s valuable. That’s remarkable.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

It includes a new account of the creation of the Earth that details how the creation was planned before it was carried out, very fascinating detail, and that it was—actually, it involved more than just God the Father and Jesus Christ, but that many noble and great ones that the Book of Abraham refers to as “the gods” helped to carry out the creation of this earth. So remarkable, stunning insights there doctrinally. And then, perhaps most poignantly, the account explains how Abraham, who is a man most known for having his faith tested by God in Genesis 22, right, where God asked him to sacrifice his son, Isaac. It is one of the most horrific stories in scripture, right, this Abrahamic test. It’s a stunning, challenging piece.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But the Book of Abraham gives us a breathtaking sort of backstory to that that even highlights and accentuates the difficulty of Genesis 22 even more, and that is that Abraham himself was nearly sacrificed as a young man by his wicked father, and so that just makes Genesis 22 all the more poignant, all the more challenging, and the impossible test all the more impossible.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So stunning book, only a few chapters long, but packed with insights. It packs a punch.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, and that last point actually is probably the reason right now why I most connect with the Book of Abraham. Instead of Abraham being this royal scion, this person destined for greatness, Abraham comes from a really messed-up family.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The father of the faithful, the person that everybody points back to when it comes to the covenants made to the fathers, came from a really dysfunctional family. And you might think your family’s dysfunctional, but your dad probably hasn’t offered you up as a human sacrifice. Abraham’s dad did.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And that makes the story of Abraham and Isaac so much more poignant down the road, because everything in Abraham must have been screaming that this is not what the Lord does, because the Lord rescues him from his dad, says that’s messed up, and then that just deepens that idea of Abraham and Isaac being the ultimate test of Abraham’s faith. How much do you trust me?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And it makes it a little bit more beautiful.

Scott Woodward:

If anyone knows about the evil of human sacrifice, it is Abraham, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And if we plucked him into the modern world and took him to, you know, LDS Family Services or something like that, there’d be a few labels that were put on Abraham, right? This is an abused child. This is someone who comes from not just a dysfunctional home, but an abusive situation. Rough background. He’s, like, the ultimate cycle breaker, too. The breaker of negative family cycles.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Admire him a lot for that. He broke some very negative cycles of abuse in his family and became the father of the faithful.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

He’s now the epitome, the poster man of what it means to be a faithful follower of God. In fact, God himself becomes known by Abraham’s name. How amazing is that, right? He’s the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, so.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And not just for Latter-day Saints. For Latter-day Saints, for all Christians, for Jews and for Muslims, Abraham’s a pivotal figure.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And so this book is a little gem that gives us background on Abraham, that deepens his story and also reveals some very powerful truths, but the Book of Abraham is probably also among our more controversial books of scriptures, and that has to do with its origins and where it comes from.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So we’re going to be dealing with the origins of the Book of Abraham, some of the controversies.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Before we get into this, Scott and I both openly admit that we are not Egyptologists.

Scott Woodward:

We are not Egyptologists. Although, I will say, there is a guy named Scott Woodward, Scott L. Woodward, who’s not me, but he worked at BYU. He doesn’t work there anymore, but he’s a microbiologist who has studied the DNA of mummies in Egypt, the mitochondrial DNA of Egyptian mummies, and honestly, I get emails sometimes from people looking me up because I’m also an LDS Scott Woodward, and they want to know Egyptological and DNA questions. And so, Casey, I do my best to answer their questions, you know? Just kidding. No, I say, “Sorry, you’ve got the wrong guy. I’m the wrong Scott Woodward.” So if anyone out there is listening and knows about the other Scott Woodward, I’ve actually never met him. Apparently, he’s a great guy. He was a bishop at BYU. Cool connections to Egyptian mummies and DNA. I am not that Scott Woodward, just to clear the air here.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And I am fortunate to have a weird enough name that I don’t get mixed up with other people often, though there is a Casey Griffiths that’s a football player—

Scott Woodward:

Whoa.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—and a Casey Griffiths that is a girl in her 20s on Twitter, and people don’t ever confuse me with either one of those. And so I wish people were sending me emails about mitochondrial DNA in mummies, but I just—that’s not my beat. At any rate, we’re not Egyptologists.

Scott Woodward:

That’s not us.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And what we do on this podcast is steal from people that have expertise—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

—but it’s not stealing if you say what you’re stealing from. So first, if you want to start into the controversies, the challenges, I’d start with the Gospel Topics essay that was published a couple years ago. It’s in Gospel Library. It’s on the Church’s website. It’s a great introduction to the controversies, but also some of the beauties and some of the great things about the Book of Abraham, why it’s so important to us, why it’s worth defending.

Scott Woodward:

It’s just a great gateway, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And most of the different series we’ve talked about, there is a Gospel Topics essay about that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And it’s just a great summary of the beauty and the controversy.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

You can read it or listen to it. It’s about a 20-minute listen, if you choose to do that. But it’s well worth your time, and it should be kind of the starting point.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Once you’ve absorbed that, if you want to go a little bit deeper, the next resource we would recommend is Let’s Talk about the Book of Abraham. There’s been this good series published the last couple of years where they published these little, tiny books, usually around 150 pages long or so, that go into controversies surrounding plural marriage—Brittany Chapman did a great book on plural marriage. Book of Mormon Translation, Gerrit Dirkmaat, Mike MacKay. Kerry Muhlestein, who is a scholar of BYU, he’s an Egyptologist, and more than that, he’s just a wonderful human being, wrote Let’s Talk About the Book of Abraham. And in 150 pages, it’s probably deeper than almost anybody will need to go to just understand the basics surrounding the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Kerry is a believing scholar, and he’s one of the most persuasive people I’ve ever talked to about the Book of Abraham, and this book is kind of a remarkable little summary of the controversies, the research, and everything surrounding the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Amen.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Next resource, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham by John Gee. John Gee is another Latter-day Saint Egyptologist. This is a little bit longer than Kerry’s book, a little bit more of a deep dive into it, and highly recommended as well, by a faithful Latter-day Saint Egyptologist. Finally, we want to put a plug in for our sister site. It’s part of Scripture Central. It’s called Pearl of Great Price Central. And if you haven’t had a chance to look at this, Pearl of Great Price Central is awesome.

Scott Woodward:

It’s so good.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And it’s free, is another big thing. You don’t have to spend any money to access these resources. It comes from some really great Latter-day Saint scholars, like Kerry Muhlestein and John Gee, and I’ll add in Stephen Smoot and a bunch of people that are doing great work.

Scott Woodward:

There are a ton of good resources there that are so accessible.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

They’re very accessible, and they’re bite-sized. It’s just a little article about this, a little article about that. So you don’t have to start from the beginning and go to the end of a book. It’s just these little articles that are tremendous.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And it’s presented in a very clear, attractive, you don’t have to be an expert, written for laymen kind of way. And so that’s another great place to start, too. They are super helpful, and they were very helpful in us preparing some of the things we’re going to talk about today.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So there’s our rundown on resources. Let’s walk through where the Book of Abraham comes from, and then we’ll start to introduce some of the controversies surrounding the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Awesome. Okay, so let’s back up, and let’s trace the timeline here of the origins of the Book of Abraham. Let’s go back to how and where Joseph Smith came to possess, among other things, a papyrus scroll from Egypt, which he was convinced contained the writings of Abraham, and then, from there, like, how does this become part of the LDS canon of scripture?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And it’s a crazy story. You wouldn’t expect Joseph Smith and Napoleon to intersect with each other, but they do! And it’s a really crazy story, but it’s also fascinating how the chain of custody for the objects linked to the Book of Abraham—how they get to Joseph Smith eventually, so.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. Wild ride. Yeah, let’s start with Napoleon Bonaparte.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So Napoleon Bonaparte, he is known for a lot of things, but one of them is his late 18th century adventures and depredations and exploits in Egypt, where he unintentionally inaugurates an age of exploration and inquiry into all things Egyptian antiquities. So in 1798, Napoleon enters into Alexandria, Egypt, and then he starts to, like, bust into tombs and graves, and there’s treasures in there. There’s all these mummies and artifacts. And after he paved the way for that, plundering in Egypt skyrockets after this point. There’s an Italian man somewhere between 1817 and 1821. His name is Antonio Lebolo. He’s an Italian explorer, he’s an antiquities dealer, and he uncovered a tomb near Thebes, Egypt, which is kind of down in the middle of Egypt and then over to the right a little bit if you’re looking on a map. And in Thebes, he found a large cache of mummies and papyri. He procured eleven mummies and some of the papyrus scrolls from that Thebes area and takes them to Italy.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, and Lebolo is fairly well known in his day. One source calls him the King of Thebes. He’s an archaeologist. Interestingly, Kerry Muhlestein has used a different term for Lebolo.

Scott Woodward:

Ooh, what’s his term?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He’s a grave robber.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Like, he’s; going in and just busting open tombs and dragging out the mummies and all the things associated with the mummies.

Scott Woodward:

He’s a grave robber.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He’s a grave robber, yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Some call him antiquities dealer, some call him grave robber, whatever.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Depends on, you know, your vantage point and your time period, but today we would call him a grave robber because he’s plundering these Egyptian antiquities. And this isn’t just Lebolo, too. These Egyptian antiquities are being spread all over Europe. This is still controversial today. They took these things from Egypt, and now they’re displayed in collections all around the world. And we’re not endorsing grave robbing; we’re just telling you what the history is here.

Scott Woodward:

Did one book of our scriptures come from grave robbing in Egypt? I mean, yeah. Okay? I mean—I mean, that happened, all right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It happened. Spilled milk. What are you going to do about it?

Scott Woodward:

Watch how good things can come from bad exploits in Egypt, okay? So here we go. So where was I? Oh yeah, so Lebolo takes these eleven mummies and papyrus scrolls to Italy, and they stay there until his death in 1830, and then his collection is then shipped to New York, and it comes into the hands of a man there named Michael Chandler. And it’s unclear the relationship between Chandler and Lebolo. We’re not sure if they knew each other or what happens there, but he gets a hold of the mummies, and he is just leaning right into this season of Egyptomania, is what it’s sometimes called, where just people were just crazy about all things Egypt, right? It’s this mysterious—nobody knew how to read the hieroglyphs. Some people thought these hieroglyphs were giving away some of the secrets of the universe. And how cool is it to go and see a mummy and then to see a papyrus scroll? So Michael Chandler would charge people, right? This was kind of this thing where he’d say, come and see these curiosities, and charge you 25 cents or whatever to come and see.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Can I add something really fast, too?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

In a lot of early sources, Michael Chandler is referred to as the nephew of Antonio Lebolo. He was not the nephew. It seems like early church members believe that, and Chandler may have led them to believe that. We don’t really know what was going on there, but we’re not totally sure how Lebolo’s collection makes it into Michael Chandler’s hands, and Michael Chandler, like you said, is touring around, and he’s also selling certain parts of the collection. Like, I think he starts with eleven mummies?

Scott Woodward:

Yep. Starts with the eleven mummies.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, and then it seems like when interest starts to wane and business isn’t as good, then he starts selling them off, piece by piece, until he gets to Kirtland, Ohio, and he’s only got four mummies left. So he had sold off the other mummies by the time he arrives in Kirtland, which is 1835. So he had heard, apparently, that Joseph Smith was a person who could perhaps even translate the ancient characters that were found on the papyri. And so someone had referred him to Kirtland, Ohio. And when he gets to Ohio—this is about late June 1835, and some of the saints pool their money together after Joseph Smith examines the mummies and the papyri. He’s not really interested in the mummies, but he’s very interested in the papyrus. Very interested in the papyrus. But Chandler says he can’t buy the papyrus without the mummies, and so Joseph says, fine. So they pool their money, and they buy the mummies so that they could also get the papyrus.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

That’s one of my favorite parts of the story, by the way, is we don’t talk about the mummies enough, that there were mummies that came along with this, and one of the sources I read said that when Joseph Smith was in Nauvoo, like, the mummies were sometimes kept in his house.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So it’s even before his death, his mom and his dad take charge of the mummies, and there’s several visitors that came to Nauvoo and said that Lucy Mack Smith basically would say, hey, do you want to see the mummies?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And they’d be like, of course.

Scott Woodward:

That’s right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And she’d be like, okay, give me a nickel. And so you pay five cents. And the most famous person to talk about this was Josiah Quincy. He’s the former mayor of Boston. But yeah, she’d take you in, she’d show you the mummies, and the mummies are kept with them. Like, they—they keep and preserve this alongside the papyri. But just to give a primary source of what we’re actually talking about here—

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, please.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

There’s a letter from W. W. Phelps, who’s one of Joseph Smith’s close associates. He’s very linked to the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He writes a letter where he says this: “On the last of June,” this is June 1835, “four Egyptian mummies were brought here. With them were two papyrus rolls beside some other ancient Egyptian writings. They were presented to President Smith. He soon knew what they were and said the rolls of papyrus contained a sacred record kept by Joseph in Pharaoh’s court in Egypt and the teachings of Father Abraham. These records of old times, when we translate and print them in a book, will make a good witness for the Book of Mormon.” And so another thing that you want to track right here, too, is how Phelps describes the collection. He says there’s mummies, there’s two rolls of papyrus and some Egyptian writings. So two rolls of papyrus and something else besides it.

Scott Woodward:

Some other Egyptian writings.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And Joseph identifies the writings as being linked to Joseph—this is Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat Joseph—and Father Abraham. So there’s the start of the idea. Joseph sees them, identifies them, and then says, we should probably purchase these.

Scott Woodward:

This is why they wanted to purchase them. And it’s interesting also: before Joseph even translates and gets any sort of Book of Abraham, they’re already talking about how this is going to be a fine addition to their scriptures. It’s going to make a good witness for the Book of Mormon, Phelps says. And let me add one more from Oliver Cowdery, too. He also says in the Messenger and Advocate of 1835, just a few months later, “When the translation of these valuable documents will be completed, I am unable to say. Neither can I give you a probable idea how large volumes they will make. Be they little or much, it must be an inestimable acquisition to our present scriptures.” So they’re already thinking this is going to add to our scripture before they even knew what the scrolls said. So we do get something called the Book of Abraham from those scrolls, but we never get the book of Joseph, the book of Joseph in Egypt. And, from what I understand, Joseph did plan on eventually translating that one, but wasn’t able to do so. Is that your understanding?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah. This is the earliest mention, where he says they contain the sacred record kept by Joseph and Pharaoh’s court and the teachings of Father Abraham. Joseph Smith begins translation—for instance, we’ve got a journal entry from November 19, 1835. So this is four or five months later: “I returned home and spent the day in translating the Egyptian records,” so.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He starts to work on it and apparently translates the first part in 1835. Then things get really busy. You’ve got the dedication of the Kirtland Temple, the Kirtland apostasy, the problems that happen in Missouri, Liberty Jail. And he isn’t able to return to it until they get to Nauvoo, when he begins translating again.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So two phases of translation: one in 1835 in Kirtland—that’s when the Kirtland Egyptian papers, which we’re going to talk about, were probably produced—and then later in Nauvoo, the Book of Abraham was first published in three installments in the Times and Seasons. That’s the Church newspaper.

Scott Woodward:

And that’s 1842, right? They’re published in 1842 in March and May in the Times and Seasons.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Now, do we know for sure now that Joseph did not finish the translation of what we currently have in the Book of Abraham in 1835? Has Kerry pinned that down or others pinned down for sure that he actually did some translation in Nauvoo, or is that still speculation? Do you know?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I don’t know. I don’t know. It seems like he probably did do some translation in Nauvoo, because in February 1843, in the Times and Seasons, John Taylor, who’s the editor, actually says Joseph was planning on publishing more of the translation. And so whether or not he’s done with the whole thing, the current Book of Abraham papers that we have don’t have anything more than what was published, and John Taylor says there’s going to be more published, and that seems to suggest that in Nauvoo he was engaged in translation as well.

Scott Woodward:

So it could be that what we currently have was fully translated in 1835, right in that time period, into early 1836, and then that he was intending to translate more in Nauvoo in the early 1840s.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

But it could also be the case that he was only partially finished in Kirtland and then later finished in the early 1840s what we currently have. Are those the two camps?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Not that it matters a ton, but I just was trying to pin that down in my mind. Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Not that it matters a ton, we’re just trying to pin down timeline.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Unfortunately, the next event in the timeline is Joseph Smith is killed in 1844.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And when he dies, the mummies and the papyri go with Lucy Mack Smith. She’s kind of been acting as the custodian anyway, but she has them, and she hangs on to them. Mother Smith expresses a desire to travel west, but she’s older and not in good health, and so she stays in Nauvoo, where Emma Smith acts as her caretaker. And when Lucy dies in 1856, Emma Smith and her second husband, Lewis Bidamon, sold the materials to a man named Abel Combs.

Scott Woodward:

By the way, I think it’s interesting and kind of fun that the mummies were with Joseph Smith’s mom and people paid a little bit to see them, and that money was actually kind of used to take care of Mother Smith, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

There was no retirement package. There was no insurance policy when Joseph Smith senior died that she somehow got a big chunk of money. In a way, this is Joseph Smith taking care of his mom, right? He’s given his mommy the mummies so that she can at least have a little bit of income coming in, which I think is just in some ways tender and adorable.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And you’ve also introduced an academic term I hope gains wide circulation, which is the mommy mummies. He gave the mummies to his mommy.

Scott Woodward:

Yes, his—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

She’s the custodian. And actually, this is—the possession of these artifacts is one of the things that is kind of a bone of contention between Brigham Young and Emma Smith after Joseph’s death, because she hangs on to them.

Scott Woodward:

Well, so, wait: So Lucy Smith dies in 1856?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yes. Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And then Emma Smith takes charge of the mummies?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yes. And Emma and Lewis Bidamon, her second husband, sell the materials to a man named Abel Combs, and shortly thereafter Combs sells at least two of the mummies and most of the papyri to a museum in St. Louis.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They’re there until 1863, when the collection is moved to Chicago, Illinois, and two of the mummies and parts of the papyri were on display in a museum in Chicago, Illinois.

Scott Woodward:

Wood Museum, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Wood Museum in Chicago, Illinois, that’s correct.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Until, unfortunately, in 1871, there’s a huge fire. The Wood Museum is destroyed. And at the time the assumption was all the materials associated with the Book of Abraham, the mummies and the papyri—the papers that Joseph Smith used, I should mention, do go west with us. The Church has those in their possession. The Joseph Smith Papers publishes these.

Scott Woodward:

That’s the translation?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Translation and the Kirtland Egyptian papers.

Scott Woodward:

And the Kirtland Egyptian papers. Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So, the mummies, the papyri are all destroyed. That’s what everybody assumes until, plot twist.

Scott Woodward:

Dun dun! Phone call, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yep. There’s a phone call from the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art to a person named Dr. Aziz Atiyah, a professor at the University of Utah. They tell them that they have several fragments of papyri that they believe are associated with Joseph Smith. And so Dr. Atiyah goes and examines them and certifies, yeah, these seem like they’re associated with Joseph Smith. In fact, when we go back and trace it, it looks like these fragments were either what Phelps was talking about when he said other Egyptian material, or that they had broken off from the main scrolls, and they had been placed in these large glass picture frames. And when Abel Combs died, he gave the fragments to Charlotte Benecke Weaver, who was just a caretaker who nursed him through his final illness. When she died, she gave them to her daughter, Alice Heusser, and then when she died, her husband sold the fragments to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1946. So there’s a lot of twists and turns, but the bottom line is they wind up at the New York Metropolitan Museum. When the Church finds out, they start negotiating, and in 1967 they secure the fragments and actually publish them in the Church magazine. So some of the Joseph Smith papyri, which people had assumed for almost a century had been all destroyed, do exist. I mean, you can look at all these papyri fragments on the Joseph Smith Papers site, front and back. And in my classes, I usually put them up and let my class look at all of them so they can say they’ve seen all the Joseph Smith papyri, and the last fragment, which is labeled “Joseph Smith Papyri Fragment 1,” is clearly Facsimile 1. It’s Facsimile 1 from the Book of Abraham. That’s how we know the link between this collection of papyri and Joseph Smith.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. And we’ll put a link in our show notes to the Joseph Smith Papers, so if you’d like to go and check these out, we have very high-quality scans of all eleven of these fragments, and you can look at them to your heart’s content.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. In fact, if you live near Salt Lake, if you go to the Church History Library, Joseph Smith Papyri 1, the fragment that has Facsimile 1 on it, is actually on display right now in the Church History Library.

Scott Woodward:

Oh, wow.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

You can walk right up. You don’t need a reservation or anything. You can walk right up. It’s in this little box where minimal light to preserve it from further decay, the light switches on, and boom, there it is. Any person can go and look at that fragment. If you want to see it in person, if you don’t live near Salt Lake, you can go to the Joseph Smith Papers site and see all of the papyri fragments that are there.

Scott Woodward:

So let me just review, make sure we‘ve got the story right, here. So these mummies and papyri come from Thebes, Egypt, because of Antonio Lebolo, who’s a grave robber—

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Correct.

Scott Woodward:

—who takes them to Italy. He dies. His collection goes to New York. Michael Chandler’s taking them around, starts selling them off after the Egyptomania starts dying down. Joseph Smith procures four mummies. Manuscripts. One of those scrolls, Joseph believed, was the Book of Abraham and the other one, Book of Joseph. Book of Abraham gets translated, Book of Joseph doesn’t because, we would assume, Joseph Smith dies in 1844, that’s why.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

The scrolls and the mummies go from his mom to Emma, from Emma to Abel Combs. Most of them go to the St. Louis Museum. Wood Museum. Chicago Fire, 1871. They’re all destroyed—we thought they were all gone until we find out that eleven fragments had survived, which are the fragments that ended up in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And in 1967 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Met, gives those to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And now we have them in our possession.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

That is a wild ride.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So what’s the connection between the papyri fragments and the Book of Abraham?

Scott Woodward:

Ooh.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Because, on the one hand, you know, this is great! We’ve got some of the papyri Joseph Smith had. We can look at it. They were unable to translate Egyptian in Joseph Smith’s time, academically, but now we can.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So let’s translate this thing. Let’s figure out what’s on it.

Scott Woodward:

Ooh, yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And what’s the finding that we come to there?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, this leads to the first of two major criticisms of the Book of Abraham, actually, the finding of those fragments, because nothing in those existing papyri fragments correspond to anything in Joseph’s Book of Abraham translation. Like, that’s a big problem, right? There is nothing about Abraham in them, period. In fact, Facsimile number 1, when modern Egyptologists look at Facsimile 1, they say that it is a funerary text called the Book of Breathings. In other words, it’s nothing remotely about Abraham. In fact, in the Gospel Topics essay on the Book of Abraham, it says this: “Mormon and non-Mormon Egyptologists agree that the characters on the fragments do not match the translation given in the Book of Abraham, though there is not unanimity, even among non-Mormon scholars, about the proper interpretation of the vignettes on these fragments.” So you can’t really see this on Facsimile 1 in your scriptures, but if you go to the Joseph Smith papers site and you look at the fragment itself, you’ll notice over to the right hand side, on the right hand side of the fragment, there is hieroglyphics in three columns. It’s, like, almost touching the picture of Abraham on the altar, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And those hieroglyphics, when translated, when modern Egyptologists translate that, they say those words right next to the picture of Abraham on the altar have nothing to do with Abraham. That’s why this is calling into question here, like, wait a second, what’s going on there if that’s not about Abraham, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And we’ll talk about Facsimile 1 in more detail a little bit later, but I just want to highlight this criticism. This criticism is important because it caused the very first feelings of like, oh shoot. Like, did Joseph Smith get this wrong?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Anything you want to say about the controversy itself before we go into some faithful responses?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, a couple things: There are several papyri possessed by Joseph Smith. The main one is called the Book of Breathings.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The Book of Breathings, like you mentioned, is a standard Egyptian funerary text.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

This comes from Kerry Muhlestein, but he said, “Joseph Smith possessed a copy of the Book of Breathings that was owned by Hor,” H-O-R, “priest in Thebes. This is one of the earliest, probably the earliest, known copy of this particular text. It focuses on Hor being rejuvenated, on his body functioning properly, on his being in the presence of various gods, and on being purified so that he could be in those presences.” That’s what the Book of Breathings is. It’s linked to this Egyptian priest named Hor, and these particular papyri fragments, like you said, both Latter-day Saint and non-Latter-day Saint Egyptologists agree, are not the source of the Book of Abraham. It’s not the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

They’ve also been able to do carbon dating tests on this, and the papyri date to a period about 200 BC, which is about 2,000 years after Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, that’s a little off the mark.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So, checkmate. Game over.

Scott Woodward:

Joseph Smith, boom. We found you out, brother.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. At least that’s how a lot of people approach it. But this does not invalidate the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

What?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And there’s a couple good reasons that you shouldn’t lose your faith over the fact that these papyri do not appear to be the source of the Book of Abraham. In fact, a couple theories on what the link could be between the two or where they are, do you want to walk us through a couple of those, Scott?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. In fact, I actually called Kerry Muhlestein one day when I was prepping to teach this to my students. I wanted to make sure I had it right because, as we mentioned, I’m not an Egyptologist, and so I called Kerry. It’s nice to have an Egyptologist in your pocket, right? So I called Kerry. I’m like, Kerry, hey, talk to me about that first criticism. What’s the deal with the hieroglyphs right next to the Facsimile 1 not being anything about Abraham?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

And he said, yeah, that one’s fairly straightforward. Of the ancient Egyptian scrolls which have pictures on them and then text right next to the pictures that we are aware of, that have been found in all of these grave robbings and exploits in Egypt, about 50 percent of those that have text right next to the picture are talking about the picture, and about 50 percent of those, the text right next to the picture is not talking about the picture. So when the artist and the author are different people, he said, you typically expect the picture to be separate from the text, and so he said that’s not uncommon. It’s actually about 50-50 that you’ll find that the text right next to the picture is not about the picture, and about 50 percent of the time it is. So that’s interesting, right? So that’s not an instant, like, gotcha, Joseph, right? As far as that goes.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

But I think there’s an even better response: Kerry said, now, that having been said, it’s important to note that eyewitnesses who actually saw Joseph translating the Book of Abraham say that he was working from the, “long roll” during the translation. Not the facsimiles. Joseph wasn’t looking at the facsimiles and translating according to any of the eyewitnesses. There’s nothing in the fragments about Abraham because, straightforward answer, Joseph didn’t translate from those fragments. He’s not looking at the text next to the picture and translating that and claiming that is about Abraham. So those are two responses that Kerry Muhlestein told me directly, and he’s published about this as well. But this idea of, the long roll is what Joseph was working from, is, I think, the most important point here.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Joseph never claimed to translate from the facsimiles. Therefore, to criticize Joseph by saying that the text next to the picture isn’t about Abraham is criticizing him for something he never claimed.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. So theory number one is Joseph Smith translated from these fragments, and it doesn’t seem like anybody in or outside of the Church thinks that’s the case.

Scott Woodward:

Nobody believes that. Yeah, nobody believes that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Theory number two is the one you just introduced, which is that Joseph translated, but not from these sources. And I’m going to introduce some of Kerry’s work here, where he went back and basically did a short categorization of everybody that saw the Egyptian materials, and what they described, and if it matches or doesn’t match the fragments that we have, specifically. So this is in an excellent article that appeared in the Journal of Mormon History that Kerry Muhlestein put together.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So we already mentioned W. W. Phelps. He talks about two rolls: a big one and a little one, and then says there’s other Egyptian materials, which could be the fragments.

Scott Woodward:

Which sounds like those eleven fragments, yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, it sounds like those fragments we’re talking about.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Oliver Cowdery. Oliver Cowdery is there. He saw them firsthand. Here’s a summary of what Oliver Cowdery describes: he says, “There were two rolls.” He says, “There was beautiful writing in red and black.” Oliver Cowdery describes vignettes, that’s little pictures, hieroglyphics, that we may have. He describes vignettes that we may not have.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And he also says he does not know how long the Book of Abraham will be. Which, if we’re just going off the papyri fragments that we have right now, there’s not enough real estate. There’s not enough material there to produce the Book of Abraham, and so them being translated from that seems very unlikely.

Scott Woodward:

Mm-hmm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay, Luman Shurtliff. Luman Shurtliff is a guy who visits in 1837, and he describes fragments mounted to a thick piece of paper. So by 1837, there’s already people saying, there’s fragments, and they have glued them to this paper in order to preserve them, basically. On the other hand, the two rolls are sometimes described as being in a state of perfect preservation. So it seems like, again, we’re establishing that there’s a big roll, a little roll, and then fragments, and in order for the fragments to not deteriorate further, they glued them to this paper, and that’s what was found in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay, in 1841, a guy named William I. Apleby sees the scrolls for himself. He says one of the rolls, and he uses the word “roll,” contains the writings of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Did you say “apple-by”?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

It’s A-P-L-E-by. So I want to say “apple-bee’s” because of the delightful restaurant, which, you know, a lot of our listeners frequent, but it’s Apleby. Maybe it’s “apple-bee,” and they just spelled it weird.

Scott Woodward:

“Apple-bee.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Let’s say “apple-bee.” That feels a little.

Scott Woodward:

That feels good. I like “apple-bee.”

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Let’s go with “apple-bee.” Okay.

Scott Woodward:

Sorry, continue.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

William Apleby, famous restauranteur, says, “One of the rolls contain the writings of Abraham. Joseph of Egypt’s scroll has the beautiful writing.” So he describes one of the rolls as Joseph of Egypt’s roll. He doesn’t say if it’s the big or the little one. He describes some vignettes that we have. Some stuff that definitely is in the papyrus that we have.

Scott Woodward:

In the eleven fragments, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

He describes some vignettes that we don’t have.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Henry Tressler, in 1838. Firsthand witness, but this comes from a secondhand account. So he saw them himself, but somebody said, yeah, Henry Tressler told me this. He said the translation is from the rolls of papyrus. He doesn’t mention fragments. He says rolls. Benjamin Ashby, this is 1843, this comes from a secondhand account, says the Book of Abraham probably comes from a roll with the mummies. This is after the fragments are separated. It’s 1843. A person whose name we don’t have, just labeled “M,” 1846, secondhand account, says the Book of Abraham seems to come from the large scroll. The roll was dark in color, the mounted fragments were light in color. This person describes vignettes not present on any papyri that we have right now, and he also says the prophet can read portions of the scroll that aren’t there.

Scott Woodward:

Whoa.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So that becomes a question of, wait, is he saying that the claim was that Joseph Smith was able to use spiritual gifts and fill in the gaps, basically? Charlotte Haven, this is 1843. This is a secondhand account. She says the long roll is the writing of the books of Abraham, the big roll. And she describes scenes that we no longer have from the other roll. Jerusha Blanchard says, this is secondhand account, the Book of Abraham comes from the long roll. And then the last source Kerry cites is Joseph Smith III, the prophet’s son, who’s our primary source to tell us that Emma and Lewis Bidamon sold the manuscripts. And this was in 1898. This is when Joseph III’s writing his autobiography. He says that the Book of Abraham was destroyed in the fire. So Joseph III just believes everything associated with the Book of Abraham’s destroyed in the fire. So if you walk through those sources, it’s clear that we have some of the papyri that Joseph Smith possessed.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

The most likely setup is that there’s this long roll, and there’s this smaller roll, and then there’s these papyri fragments that they have to mount in order to preserve them.

Scott Woodward:

Mm.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

But nobody is describing fully what we have right now. They’re always adding in things that we don’t have.

Scott Woodward:

Right.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

So one easy way to deal with this is to just say we don’t have the papyri that Joseph Smith used as the source of the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

And that sounds right, right? That if these two scrolls, these two rolls of papyrus go to the Wood Museum that are then destroyed in the Chicago Fire, then, yeah, we don’t have access to the source material, which it sounds like from that list of witnesses that you just mentioned, that they are pretty unified in saying that Joseph translated from the long roll or one of the rolls, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Most of them are saying the long roll, so it sounds like the shorter roll is the roll of Joseph of Egypt, which has the more beautiful writing visually, and that the longer roll is the Book of Abraham or the scroll of Abraham. And then you have these eleven fragments that are not really connected to the story of Abraham. And those two rolls go one way to the museum in Chicago, and those eleven fragments go a different way, and because of the Chicago fire, all we have left are the eleven fragments.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Which actually makes sense of this line from the Gospel Topics essay on the Book of Abraham. So that’s the backstory. Now listen to this: “It is likely futile to assess Joseph’s ability to translate papyri when we now have only a fraction of the papyri he had in his possession.” Right? We’ve only got the eleven fragments, not the two rolls.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So it goes on, “Eyewitnesses spoke of a long roll or multiple rolls of papyrus. Since only fragments survive, it is likely that much of the papyri accessible to Joseph when he translated the Book of Abraham is not among these fragments.” So there you go. So that’s actually—with theory number two of translation, if you said, okay, Joseph translated by revelation from the long scroll that was destroyed in the fire, that’s actually a relatively safe position to take, right? Because you can’t prove it, you can’t disprove it, because the scroll itself has been destroyed, and so we’re kind of left with that. And it does sound like, from all the eyewitnesses, that’s what everybody believed happened, that he translated from the long scroll, and that was destroyed. So there’s no way to be able to assess Joseph’s ability to actually translate papyri.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Now, we should mention there is a third theory that’s out there, and that is that Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham without any part of physical papyri, that this translation was something like the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, where it comes by inspiration, where we’re not talking about working with original manuscripts. An example of this would be something like Doctrine and Covenants 7. Doctrine and Covenants 7 is a passage from the Gospel of John that, when it first appeared in the Book of Commandments in 1833, it actually said it was on a parchment, but Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery, who received the section, never claim that they have the parchment. They claim that they saw the parchment through the use of the divine instruments that they used to translate, and that’s what they translated section 7 from.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, that Joseph looked into his seer stones and saw a parchment, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And then from that parchment came the translation that is now Doctrine and Covenants 7.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Yeah. And so could it have been received directly by inspiration?

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

There are some sources that support this view as well: That he didn’t use physical papyri, that he just translated it directly.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

For instance, this is a person who’s kind of antagonistic towards the Church: Warren Parrish, who acts as Joseph Smith’s scribe, he later on kind of becomes the ringleader of the Kirtland apostasy. He said, “I penned down the translation of the Egyptian hieroglyphics as Joseph claimed to receive it by direct inspiration from heaven.” So he’s saying that when he worked with Joseph Smith, said he was receiving the text of the Book of Abraham by direct inspiration.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, so there’s this line also in the Gospel Topics essay, which is describing this third theory of translation, which says, “Alternatively, Joseph’s study of the papyri may have led to a revelation about key events and teachings in the life of Abraham, much as he had earlier received a revelation about the life of Moses while studying the Bible. So we have these eyewitnesses saying he’s looking at the scrolls, right? He’s studying the scrolls. And then he’s also getting revelation about Abraham. Now, what exactly the connection is between what’s actually written on the scrolls and the revelation he’s receiving, that’s a different story.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Right? That’s something that we can’t assess because the scroll has been destroyed, but what we know is he’s looking at scrolls, and then he’s receiving revelation. And so I’ll continue to quote from the Gospel Topics essay: “This view assumes a broader definition of the words translator and translation. According to this view, Joseph’s translation was not a literal rendering of the papyri as a conventional translation would be. Rather,” here’s the key part, “the physical artifacts provided an occasion for meditation, reflection, and revelation. They catalyzed a process whereby God gave to Joseph Smith a revelation about the life of Abraham, even if that revelation did not directly correlate to the characters on the papyri.” So that’s interesting.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And this is called the catalyst theory of translation, right? That the Book of Abraham, wherever it was, whether it was on that text or not, whether it was more like D&C 7, where Joseph is getting an actual translation of a record that’s not currently in his possession, he’s got these scrolls. I think it’s clear from the history he believes they are the Book of Abraham. I think that’s pretty obvious, that he believes the scroll in front of him is the Book of Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

And the result of his translation efforts is what we now have in the Book of Abraham. But Joseph never could read Egyptian. All we know is that he studied the scroll, and we got the Book of Abraham.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Mm-hmm.

Scott Woodward:

In fact, it’s interesting: In our new 2013 heading in our scriptures, it kind of allows for this catalyst theory. It’s a little different than how it used to be written. This is the introduction heading for the Book of Abraham in our scriptures. Back in 1981, it used to say, “The Book of Abraham, a translation from some Egyptian papyri that came into the hands of Joseph Smith in 1835.” Now the new edition, 2013, says, “The Book of Abraham, an inspired translation of the writings of Abraham.” Now note this line: “Joseph Smith began the translation in 1835 after obtaining some Egyptian papyri.” So that’s what we know. That’s the more carefully written. He got some papyri, and then we’ve got the Book of Abraham, and what exactly the connection is between those two, we don’t actually know.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So that’s interesting.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. Let’s review the three theories really fast.

Scott Woodward:

Okay.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay, so theory one is the fragments that we have are the source of the Book of Abraham. That appears very unlikely. Very unlikely.

Scott Woodward:

The eleven fragments, yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Not a chance. No one believes that.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Okay. Theory number two is that we don’t have the papyri that Joseph Smith translated from. Tons of evidence for this. The papyri that we do have doesn’t match the descriptions of people that saw it. And so, if that’s the case, the papyri were either destroyed or we don’t have them, or whatever, right now Joseph Smith translated from.

Scott Woodward:

So the long scroll was destroyed in the fire, therefore we can’t assess whether or not it actually was talking about Abraham, so that’s a moot point either to defend or to attack, right?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah, yeah. And theory number three was a catalyst theory: the idea that having these Egyptian materials caused Joseph Smith to start to think about these things—Abraham’s linked to Egypt in the Bible. He goes to Egypt—and it opens up revelations. There’s both people that are antagonistic towards Joseph Smith and people that are supportive of Joseph Smith that say he talked about translation in these terms, that it came by direct inspiration from God. It also brings me back to that eyewitness who said Joseph Smith could see portions of the scroll that weren’t there, which I guess kind of combines theory two and theory three, saying that the scrolls were incomplete, but Joseph Smith was able to complete them through divine inspiration.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And so we’re so far only talking about the text of the Book of Abraham, but it seems like there’s a lot that we don’t know, and there’s still plenty of room to say that Joseph Smith had these materials, translated either from these materials or was inspired by these materials, that the Book of Abraham comes from God.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, and that’s consistent with his other translation projects, right? Like the Book of Mormon, which was actually written in Reformed Egyptian. By the time Joseph was done translating the Book of Mormon, he still couldn’t read Reformed Egyptian. At the end of the day, it came by the gift and power of God. It came by revelation. He got revelation through the use of seer stones, and there was little, if any, actually looking at the text of the Book of Mormon plates, right? He’s not running his finger along the hieroglyphs, as far as any eyewitnesses say. He’s actually just getting revelation through the instruments that were prepared for that purpose, as he focuses his faith on the plates themselves, right, and asks for revelation to come. So that’s the Book of Mormon.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah. And the same with the Bible. When he translates the Bible, he’s not claiming that he has the original manuscripts or that he can see them in vision. He is saying, by the means of the Holy Spirit, I am translating, and that’s the word he uses, translating. So all this is consistent. All this is totally consistent.

Scott Woodward:

The parchment of John that we just talked about in D&C 7, again, Joseph never claimed to be able to read Greek. But the parchment was written in Greek, and then he got a translation in English through the use of seer stones here. And so let’s review. Book of Mormon? Revelation. Parchment of John? Revelation. JST? Revelation. Book of Abraham?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Right? Revelation. Here’s John Whitmer, early church historian. He records in July 1835 that Joseph Smith, “by the revelation of Jesus Christ could translate these records, which gave an account of our forefathers, even Abraham.” So John Whitmer is at least recording what Joseph Smith was claiming, right? And this is not surprising. This is Joseph Smith’s M. O. It’s by revelation. And you quoted Warren Parrish earlier, that he says that Joseph, “claimed to receive it by direct inspiration of heaven.” He’s talking very much as an antagonist, but the story is consistent. Joseph claimed to translate the Book of Abraham the same way he ever claimed to translate anything, which was by revelation, not by learning the underlying source language, right? He’s not learning Egyptian, Reformed Egyptian, Greek, anything like that. It’s just by the gift and power of God. That’s how Joseph always claimed to translate.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Correct. And so it would be easy for us to just look at the fragments and dismiss them and say, “This isn’t the source of the Book of Abraham. Case closed.” But now we’ve got to confront the second big criticism of the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Ah, shoot.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

You can’t dismiss the fragments because Facsimile 1 is among the fragments. So the fragments are linked to the Book of Abraham in some way.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And that brings up the second major criticism of the Book of Abraham, which is the facsimiles. Returning back to where we started, Scott, the pictures that come along with the book are where a lot of critics of the Book of Abraham make their hay in attacking and going after Joseph Smith.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah, because they say—not just Facsimile 1, but especially, like, Facsimile 3—if you go to Facsimile 3, you’ll notice there’s these little hieroglyphs, and in those hieroglyphs, you’ll see these tiny, little numbers, and those numbers then correspond down in your footnotes to a translation.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

So critics say, now we can finally assess Joseph Smith’s ability to truly translate because here’s a hieroglyph, here’s a little number, and down in the footnotes there’s an English translation that we assume came from Joseph Smith. And modern Egyptologists who look at those same hieroglyphs and then look down at Joseph Smith’s translation say he got it totally wrong.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Yeah.

Scott Woodward:

Uh-oh. So their verdict is, with the limited manuscripts that we have, these eleven fragments, we actually have, on Facsimile 3, we’ve got Joseph Smith actually, on paper, translating, and he gets it totally wrong. Therefore, we now know Joseph Smith cannot translate. All of his claims to be able to translate by the gift and power of God are false. Checkmate. Game over. Joseph Smith is a fraud. That’s criticism number two.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Is that where we’re going to end the episode?

Scott Woodward:

Oh shoot, we are out of time.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Oh, no. Let’s say that’s a cliffhanger. That’s a cliffhanger.

Scott Woodward:

Join us next time as we explore the faithful Egyptological responses to that second criticism. I don’t know, what do you want to say to kind of smooth this over?

Casey Paul Griffiths:

I’m going to say tune in next time, and we will tackle this particular issue with the facsimiles, because it’s more complicated than that kind of simplistic explanation is, that Joseph Smith was just wrong when it came to the facsimiles. Actually, it’s more complicated.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

And so we’re going to deal with that next time, and we’re going to talk a little bit more also about some of the other papers associated with the Book of Abraham.

Scott Woodward:

Yeah. And I will say that second criticism is probably the one that rocks the most people that get rocked by this kind of stuff. That second one feels like case closed on Joseph Smith as a translator, right? But we’re here simply to assure you, listener, that is not case closed. Join us next time, where we will dig into the complexities of it and try to unravel that with the help of modern believing Egyptologists who have grappled with this and I think come up with some really fascinating answers.

Casey Paul Griffiths:

Great cliffhanger.

Scott Woodward:

Thank you for listening to this episode of Church History Matters. In our next episode, Casey and I dive headlong into the biggest controversy surrounding the facsimiles of the Book of Abraham, which is this: Is it possible to reconcile Joseph Smith’s interpretation of the facsimiles, which ties them to Abraham, with that of modern Egyptologists, which say they have nothing to do with Abraham? We’ll look at what some modern Egyptologists have discovered about how Egyptians and Jews in the time and place where these papyri were written sometimes repurposed Egyptian facsimiles to tell stories about the life of Abraham. Might this hold a key to resolving this dilemma? Stay tuned. If you’re enjoying Church History Matters, we’d appreciate it if you could take a moment to subscribe, rate, review, and comment on the podcast. That makes us easier to find. Today’s episode was produced by Scott Woodward and edited by Nick Galieti and Scott Woodward, with show notes and transcript by Gabe Davis. Church History Matters is a podcast of Scripture Central, a nonprofit which exists to help build enduring faith in Jesus Christ by making Latter-day Saint scripture and church history accessible, comprehensible, and defensible to people everywhere. For more resources to enhance your gospel study, go to scripturecentral.org, where everything is available for free because of the generous donations of people like you. And while we try very hard to be historically and doctrinally accurate in what we say on this podcast, please remember that all views expressed in this and every episode are our views alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of Scripture Central or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Thank you so much for being a part of this with us.

Show produced by Zander Sturgill, edited by Nick Galieti and Scott Woodward, with show notes by Gabe Davis.

Church History Matters is a podcast of Scripture Central. For more resources to enhance your gospel study go to scripturecentral.org, where everything is available for free because of the generous donations of people like you.